Political prisoners and the art of resistance project

Quite recently, we have witnessed the vehemence of incoming President Duterte to resume the peace negotiations with the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP) and other State-tagged “rebels”, thereby reviving the issue of political prisoners and their lamentable condition in the public discourse.

Political prisoners, or prisoners of conscience, as dubbed in other culture, are individuals who are incarcerated because of their political position or ideology that are often perceived to be antagonistic or even revolutionary by the State.

There are about 540 political prisoners in the country, including 18 peace consultants of the NDFP, 88 medically-ill and 48 elderly, according to the May 18, 2016 report of human rights watchdog KARAPATAN Alliance for the Advancement of Peoples’ Rights.

It is pivotal to understand that the victimization of the political prisoners is provoked by the historical and political nature of their struggle.

The struggle to mobilize the workers in the countryside, for one, was subjected to red-tagging and McCarthyism when the dictatorial regime of Marcos legitimized Martial Law through various Presidential Decrees that suppressed critical institutions like mass movements and the media. And the self-same strategy lived on when the regimes of Macapagal-Arroyo and Aquino III contrived the Oplan Bantay Laya and Oplan Bayanihan, respectively – the counterinsurgency campaigns aimed at persecuting the critical voices of peasants and workers, political activists, indigenous community leaders, Church leaders, among others.

In spite of restrictions in almost every aspect of a political prisoner’s struggle, how is the individual and collective notion of freedom sustained behind the repressive prison system? How, then, is the assertion of a political space take place within and outside the prison?

In this article, allow me to look at the context of resistance of various artworks of the political prisoners featured at the exhibit Sa Timyas ng Paglaya (In the Comfort of Freedom) at the Bulwagan ng Dangal (Hall of Honor), University of the Philippines Diliman from June 11-25, 2016.

The artworks, first and foremost, are a delineation of the phenomenological state of the political prisoners.

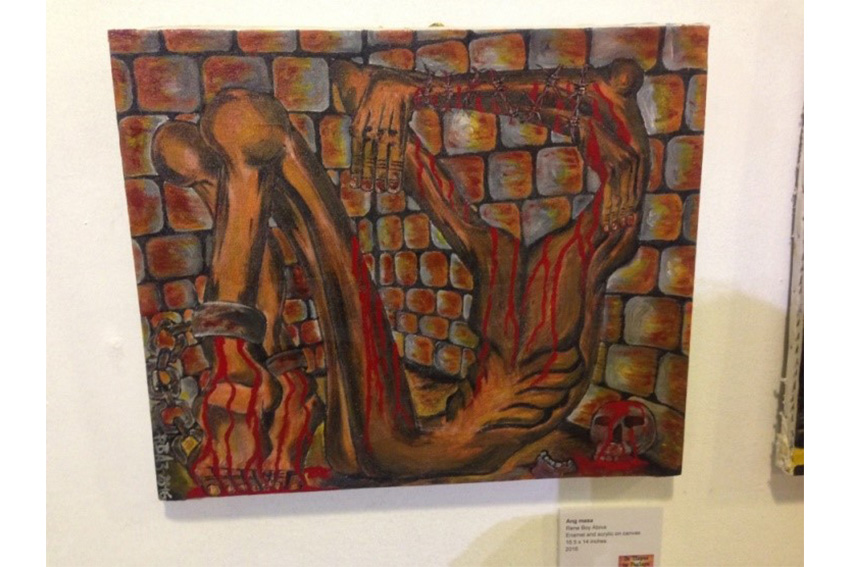

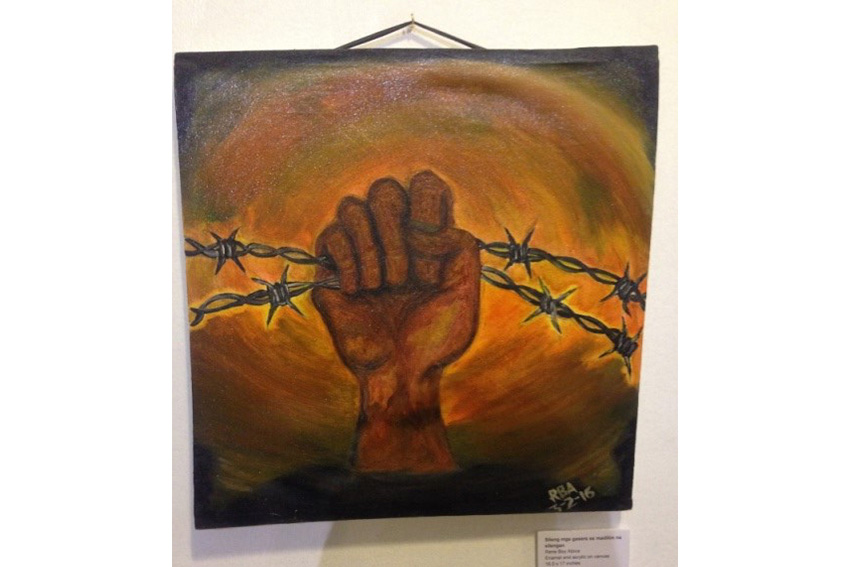

The paintings Ang masa (The masses) and Silang mga gasera sa madilim na silangan (The traditional lamps in the gloomy east) by Rene Boy Abiva portray the atrocious state of the political prisoners inside the detention. The artworks also juxtapose the condition of the masses with those incarcerated where the State and powers-that-be will never fail to instigate political retribution to those who will dare contest its economic and political hegemony. On the contrary, the clenched bulb wires indicate the enduring dedication to break away from the shackles of subjection notwithstanding continued political harassments against the ranks of political prisoners and their families.

Ang masa (The masses) by Rene Boy Abiva

Silang mga gasera sa madilim na silangan (The lamps in the gloomy east) by Rene Boy Abiva

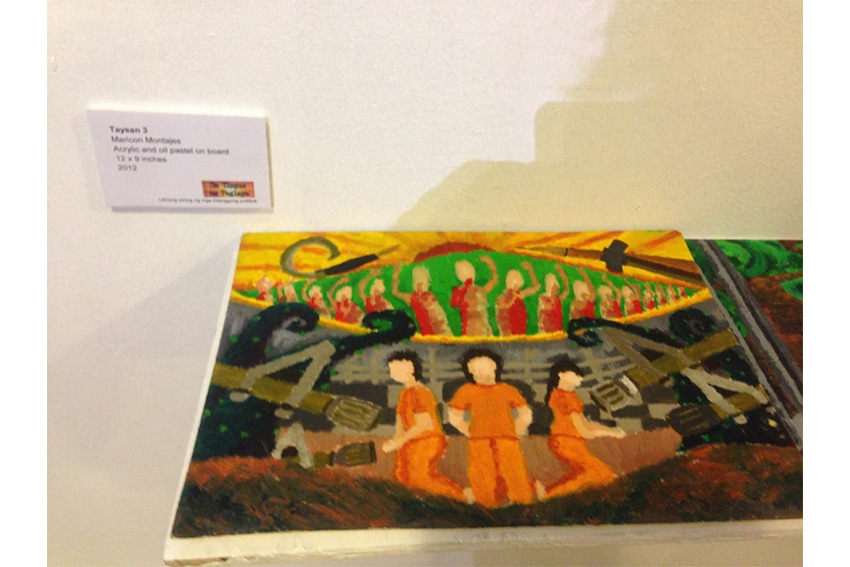

Maricon Montajes, a member of the Taysan 3 – a group of three political prisoners detained at the Bulacan Provincial Jail – recalls in her painting the illegal capture of the group as they were conducting an integration activity in Mabayabas, Batangas in July 2010. According to reports by human rights watchdogs, they were threatened with guns, harassed and tortured, and, one of them, Ronilo Baez, was even forced to admit that he was a member of the New People’s Army.

Taysan 3 by Maricon Montajes

The artwork of Voltaire Guray illustrates how lives inside the prison system are afflicted and ruined by the mechanisms set by the system itself. The symbolic death of the individual is further characterized by morbid environment, desolation, torture of the minds, and physical exhaustion.

Artwork by Voltaire Guray

In addition, the artworks are a manifestation of sustained political struggle and social aspirations.

The painting Flag Dance by Eduardo Sarmiento portrays a rural community that has long aspired for equality where the collective struggles are celebrated and the community members themselves are honored for sustaining such communal act.

Flag Dance by Eduardo Sarmiento

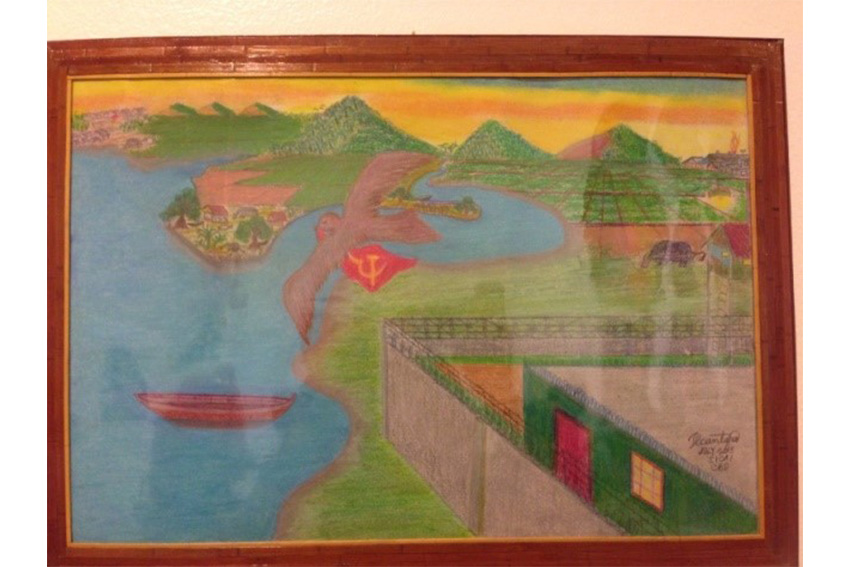

A similarly-themed painting by Tirso Alcantara ruminates on a tranquil countryside that appeals for a nationally-industrialized operation of the agricultural lands. The pigeon holding the red flag with hammer and sickle in it symbolizes the aspiration to liberate the workers from a class-based society and move towards realizing the united agenda for peace and development.

Artwork by Tirso Alcantara

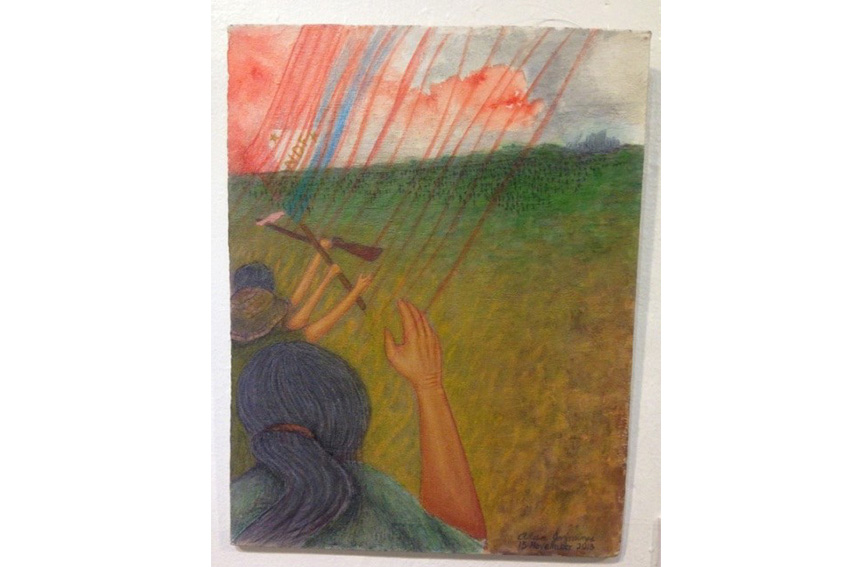

Alan Jazmines, in his artwork Lakbay-Salubong sa Pakikibaka (Journey in the Struggle), also projects a social cause that despite long hours and years of struggle, the workers will continue to cultivate hopes in their lands and rejoin their families and children to memorialize the aspirations for collective freedom and emancipation.

Lakbay-Salubong sa Pakikibaka (Journey in the Struggle) by Alan Jazmines

Considering the restricted position of the political prisoners in public discourse, we must look at these artworks as a means of resistance against State hegemony and against the political prisoners’ further marginalization in the public.

The artworks paved the way for the political prisoners to challenge the dominance of the State by putting forward a collective perennial voice against political sabotage of critical voices in society. At the same time, the existence of political artworks communicated the very existence of the political prisoners to the eye of the public, thereby creating a public space that is essential in the advancement of social and political aspirations exhibited in the aforementioned artworks.

Thus, the utopian longing of a culture is intrinsically anchored on the hopes and resistance of the marginalized, as in the case of the political prisoners. As Alcantara pointed out in his poem Ang Maging Bilanggong Pulitikal (To Be a Political Prisoner): Sa araw-gabing kahirapan, pananakot at panlililanlang / Ang minimithing kalayaan ng Mahal na Inang Bayan / Hinding-hindi mawawalay sa diwa’t katawang lumalaban (As we suffer day and night, threatened and deceived / Our aspiration to liberate our Beloved Mother Land / Will never fade away from our spirit of resistance).