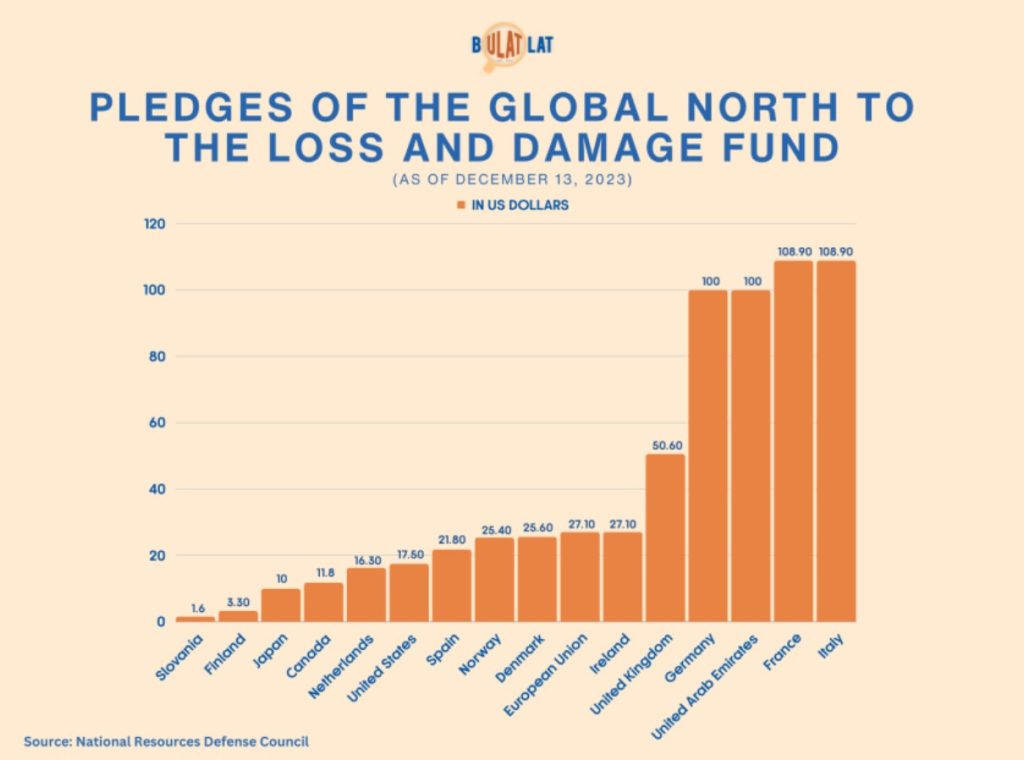

DUBAI – During the 28th Conference of the Parties on Nov. 30 to Dec. 12 held in Dubai, world leaders have officially launched the loss and damage fund (LDF). According to a report, at least 15 developed countries and the European Union have announced their pledges during the summit, which totaled almost $700 million ($655.9 million).

The United States, which is one of world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitters, is among the countries with the least pledge, which is $17.5 million. Among the countries with the highest pledges are the United Arab Emirates and Germany with $100 million each and France and Italy with almost $110 million each.

Civil society organizations (CSOs) called the US’s pledge a measly contribution compared to its aid for war and militarization. They also demand that the funds should truly serve the communities in the Global South.

But what is loss and damage fund and why developed countries are contributing to fund it?

According to Lia Mai Torres, executive director of Center for Environmental Concerns (CEC), the LDF has emerged from decades of lobbying by the most affected and vulnerable countries.

“It is based on the concept of climate justice where countries, who, historically have the highest emissions, including the United States and the European Union, must provide finance to the countries most affected and vulnerable that are now experiencing the worst impacts of climate change,” Torres told Bulatlat in an email interview.

These most affected and vulnerable countries include countries under the alliance of small island states, who, in 1991, pushed to create a mechanism to compensate vulnerable countries who experience impacts of change in climate such as rising sea levels.

“The reality for them is that they are losing the island as the sea level rises. That forced them to become climate refugees or climate migrants which was not their doing. It was caused by the Global North and the corporations. For them it’s beyond adaptation,” explained Wanun Permpibul of Climate Watch Thailand and a member of the Asia Pacific Forum on Women Law and Development (APWLD).

Fund too small

Although the operationalization was lauded by many, the civil society organizations (CSOs) said funds pledged by the developed nations are not enough for the reparation of countries bearing the brunt of climate change.

For Permpibul, the $700-million pledge is a measly amount compared to the needs and scale of impacts being confronted by the communities in the developing countries.

“This is so little. We need to make sure that our demands in climate finance are heard and demand accountability on the Global North and corporations as well,” Permpibul said.

For one, Vibuthi Josh, deputy director of Centre for Community Economics and Development Consultants Society cited the data of UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UN ESCAP) saying that in 2022 alone, the Asia Pacific suffered over 140 disasters leading to 7,500 deaths, affecting 64 million people and caused economic damage amounting to $57 billion.

“The most vulnerable sub-regions and countries experienced heightened inequality and devastation in the agriculture and energy sectors compromising food and agriculture and energy security,” Josh said during a side event in Dubai on Dec. 10.

She added that the cost of damage in the recent flooding in Pakistan was over $30 billion. “India on the other hand has seen over $3.5 trillion in losses in over 30 years according to the University of Delaware,” Josh said, adding that the estimated cost of climate-related damage could be a total of $400 billion per year by 2030.

Josh also said that based on their experience of working closely with the rural communities in India, the impacts of disasters in rural communities are also changing.

“More than physical damage, communities face distress due to disruption of services, livelihoods, education, rising debts and long-term impacts especially on the low income groups. There is too little being done and too late. People don’t even get 25% of what they have lost. People in the lower income brackets may take decades to overcome the losses,” Josh said. She is also involved in a Pan-Indian collective MAUSAM, an initiative to promote sustainable development, equity, and climate justice in South Asia.

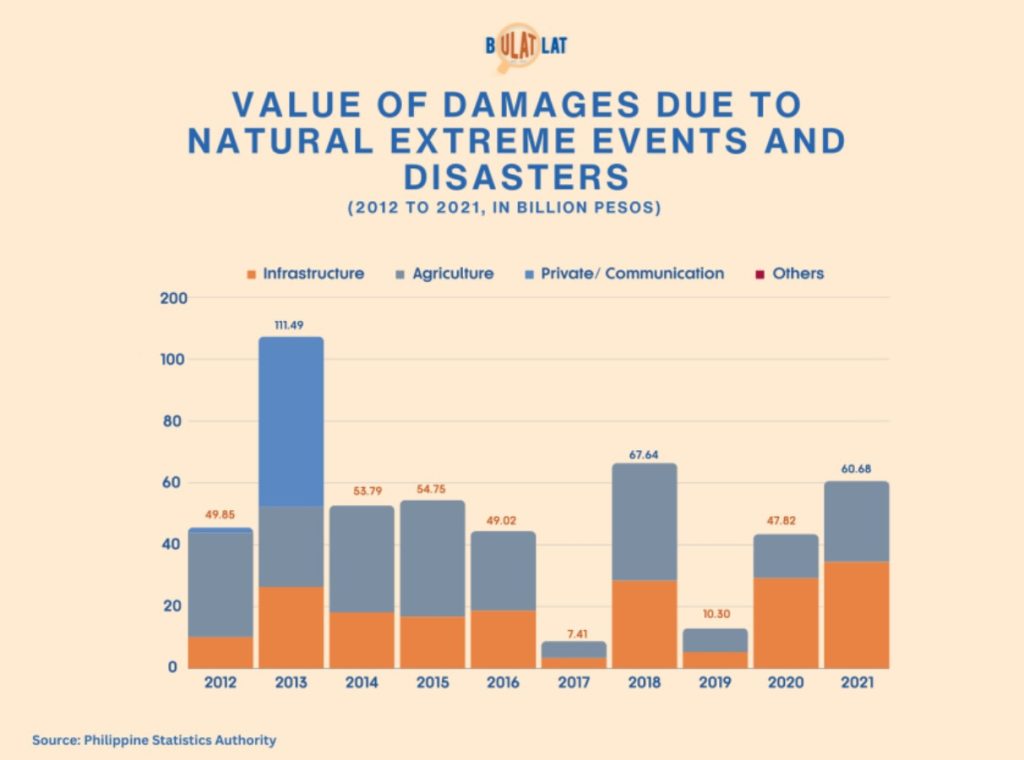

Meanwhile, the Philippines also suffered billions worth of damages due to typhoons. The total cost of damage of typhoon Haiyan alone is worth $2.2 billion, typhoon Rai with $1.02 billion and typhoon Bopha with $1.06 billion.

Ten years after typhoon Haiyan struck the islands of Samar and Leyte, those who survived are still grappling with limited access to social services.

READ: A decade-long suffering: Yolanda survivors still deprived of essential services

Data from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) from 2012 to 2021 showed that the Philippines has recorded billions of damages due to natural extreme events and disasters. The highest amount recorded was in 2013 amounting to P111.49 billion ($2 billion). The second was in 2018 with P67.64 billion ($1.2 billion) and in 2021 with P60.68 billion ($1 billion). The data includes damage to infrastructure, agriculture, private/communication among others.

World Bank as host of loss and damage fund

While many CSOs welcome the operationalization of the loss and damage fund, they too are apprehensive with the World Bank as interim host of the fund.

Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights in the context of climate change, Ian Fry, also expressed his reservation about the World Bank as host of the LDF. He sees several conflicts such as the bank’s board is dominated by developed countries and it also finances fossil fuel projects. In a report, Fry said donor countries might have influence or can override decisions around the fund.

Chennaiah Poguri, spokesperson of the Global People’s Caravan and national secretary of the Andhra Pradesh Vyvasaya Vruthidarula Union (APVVU), a federation of farmers, agricultural workers, landless peasants, and other working rural peoples in India, said that the rural peoples reject the World Bank as the interim host of the fund.

“The WB has historically used public coffers to guarantee profits for private corporations. Funds meant for climate victims, the majority of which are poor and dispossessed rural peoples, should not be used to impose conditionalities on and increase the debt burden of countries in the Global South. This would be tantamount to robbing a gravestone,” he said.

Instead, he said that the LDF, “should be managed by an independent and credible entity acceptable to the Global South, and which will ensure easy access for all countries claiming climate compensation.”

Torres, on the other hand, pointed out the World Bank’s track record as an international financial institution, saying that not only it pushes countries into extreme debts but it also funds projects that have negative impacts on the environment and have caused human rights violations.

“It is even more worrying and puzzling whether the funds will actually be distributed and be used in the framework of climate justice,” Torres said.

Ivan Enrile, climate justice program manager of Ibon Foundation, said that the World Bank currently hosts the Global Environment Fund (GEF), which was supposed to be temporary at the beginning but he said, it is still being hosted by the World Bank.

CSOs also assert that LDF should be new and additional and should not be in the form of loans. It also should be accessible to the communities of the developing countries.

Permpibul said that in the Green Climate Fund, those who have direct access to the funds are international and regional institutions. “Communities who are at the climate forefront do not have direct access to the fund,” she said.

The GCF is another UN-related climate fund. According to the National Resources Defense Council, the GCF is the “world’s largest multilateral fund dedicated to helping developing countries address the climate crisis.”

The GCF was created in 2010. In 2014, it had an initial resource mobilization of $10.3 billion pledges from 45 countries. There is also the Adaptation Fund which finances projects and programs that will help vulnerable communities in developing countries to adapt to climate change.

“If the LDF is to provide support to the communities, we would need to make sure that there is direct access and the fund reaches the most vulnerable communities. Not to international financial institutions. The fund should benefit those at the climate forefront,” Permpibul asserted.

Poguri said that LDF is an important initial step in bringing justice to rural peoples in the global south as they suffer the consequences of climate change such as extreme droughts, tropical cyclones, floods, and sea level rise.

But he added that the current pledges show the developed countries’ insincerity and lack of accountability for historic and current emissions.

“For the past decade, losses in agriculture are estimated at $11 billion a year, with countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America disproportionately accounting for the biggest losses. These pledges are but a ‘drop in the ocean,’ and may end up being just for show if there continues to be no clear commitments to long-term mandatory financial obligations,” Poguri said.

Philippines gets a seat at LDF inaugural board

After the COP 28, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) announced that the Philippines gets a seat on the inaugural board of the loss and damage fund.

In a report, Environment Secretary Toni Yulo-Loyzaga said that having a seat on the inaugural board would give the Philippines the opportunity to influence the decision-making on who gets to have access to the fund.

While getting a seat at the loss and damage fund inaugural board shows recognition that the Philippines is vulnerable to climate change, Torres said it is also worrisome given the track record of the Philippine government in responding to disasters.

“One decade after Haiyan many people have yet to fully recover from the impact of the typhoon. Farmers are losing their crops due to typhoons and drought. Add to that the issue of improper use of the funds and corruption,” Torres said.

READ: Citizens criticize Marcos Jr.’s absence in hardest hit areas, low budget for disaster response

READ: Stand with Samar | Farmers take gov’t to task for not addressing their plight

READ: Kabankalan rice farmers need aid after onslaught of Odette

READ: In the Philippines, typhoons shatter myth of disaster resiliency

READ: DSWD memo disqualifies poor as beneficiaries — Visayas disaster victims

Torres also said that the government is also pushing false climate solutions such as nuclear energy – one form of non-renewable energy and mega-dams which have great impacts on the environment.

“There is also a jeepney phase-out which the government claims to modernize the transportation. But drivers cannot afford to buy these modernized vehicles,” Torres said.

READ: Jeepneys’ just energy transition bogged down by lack of support

The government purportedly wants to reduce emissions with the public utility vehicle modernization program. Government data show that only two percent of the total registered vehicles in the Philippines are jeepneys or over 250,000.

The CEC also said that “instead of scraping vehicles from other countries, it would be sustainable to develop and improve national industries that will support local public transportation. This shall not only improve the local economy but also promote genuine inclusive climate resilience and adaptation.”

Torres also said that attacks against environmental human rights defenders and climate activists are also increasing. “Instead of looking into their contribution to protect the environment and in addressing climate change, the government is treating them as an enemy,” Torres said.

“In this context, the Philippine government cannot be considered worthy of being part of the loss and damage fund board,” Torres said. (reposted by davaotoday.com)

DISCLOSURE: The author is a media fellow of the Asia Pacific Forum on Women Law and Development (APWLD).

climate change, COP28, environment, Global South, philippines