Activists simulate drawing of chalk outlines to condemn extrajudicial killings. Photo taken during the 2018 SONA rally in Quezon City by Angelo V. Suarez.

Sure, many art practices have been winging it via online platforms since 2020 but the uncompromising nature of street arts can teach us a thing or two about the non-negotiability of physical and public spaces to artmaking, especially in times of crisis, under authoritarian regimes.

Thanks to privatization, people’s access to public spaces has already been dwindling pre-pandemic. Malls outnumber public parks. Land developers displace communities. COVID-19 lockdowns just made it worse to the point of normalization. The streets, one of the few remaining spaces where encounters are not necessarily dictated by purchasing powers, for a time became inaccessible alongside our mobility and cultures unique to this space—children playing, teens skateboarding, people crowding around street food, walking, jogging, cycling, sitting on the sidewalk, or holding street parties on occasion.

In the time of what is dubbed as “new normal,” when work and school are expectedly going to be half-virtual and people will be staying at home half of the time, not going out to the streets as often may no longer be a concern if people will get used to it. This in itself, is a concern.

How important are public spaces, specifically the streets? For Duterte, it is everything. The streets have been a stage for his regime’s performative killings, a gallery for the exhibit of slain bodies after each act. The streets’ public nature has been instrumentalized to instill fear among people in swift and encompassing ways. But the Duterte regime knows fear may be fleeting and permanence is a necessity. Taking after Marcos, he endeavors “Build Build Build” to cement so-called legacy, all the while erasing historical markers from public memory.

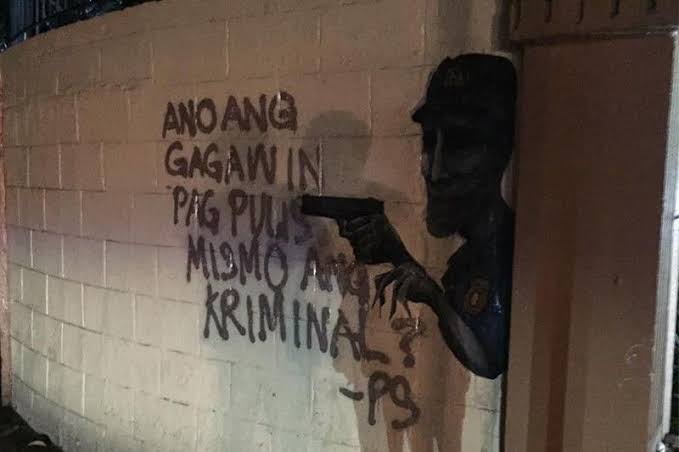

A graffiti in Manila by Panday Sining. Photo courtesy of The Philippine Star

Just as it inspired and has been replicated by Duterte, this Marcosian tactic also seems to have gained popularity among some Metro Manila mayors.

In December 2019, Manila cops snatched members of Panday Sining from a jeepney for their graffiti painted along Recto avenue during the Human Rights Day rally.

To have allowed this was expected of Mayor Isko Moreno who is known for blocking spaces of people’s protests and for the gentrification of Manila. For him, graffiti is such an eyesore that he even bothered to have them covered with dull paintings of a Nilad plant along Taft avenue (yet he had a piece of Berlin Wall filled with graffiti installed near the City Hall).

The same was carried out in Valenzuela many years prior. Back in college days on my way to the university, I would look by the window of the jeepney and catch sight of the arresting murals by whom I assumed then was an anonymous artist. The murals, always depicting a family in abject poverty, made a lasting impression on me as a young spectator. But not long, they were replaced with paintings of overlapping shapes in pale colors which surely no child would consider even remotely imaginative, ever. Congrats, Mayor Gatchalian, for dwarfing your constituents’ visual inquiry.

“Para sa Iyo Apo” mural by Archie Oclos in Sitio Pidpid, Porac, Pampanga. Photo by Rogene A. Gonzales

These efforts at sanitation-cum-censorship are not limited to cities in Metro Manila. They are being carried out too in the countryside—especially in the countryside.

In my personal encounter with muralist Archie Oclos during an immersion in an Aeta community he recounted how he was harassed by the military for his murals that encourage defense of indigenous people’s rights.

Others were not as lucky. In July 2021, two activists were shot dead by cops in Albay just for doing graffiti. Unfinished, it hauntingly read: “Duterte Ibags[—]”

We do not know exactly when it has become acceptable to mete out a couple of spray cans with guns but certainly, intensifying state control over public spaces is deathly to free expression.

Rising to the occasion, artists are doing alternative ways to fight back.

A few weeks before the lockdown, the Concerned Artists of the Philippines (CAP) projected the face of Duterte in a wanted poster to the walls of no other than Camp Crame.

Leaving no trace after projection, how could the digital graffiti artists be faulted for vandalism? In Brooklyn four years prior, a group called The Illuminator mounted a projection art in honor of Snowden, a whistleblower from the National Security Agency (NSA). “Projections have long been used for social commentary, especially in theater… The result is an attention-grabbing method of protest, one that has raised questions about legality even as it brings what activists call new opportunities for conversation,” (Segal, 2017).

A train wrapped in ads. Photo courtesy of Daily Tribune

The middle class’ elite understanding of the arts makes it easier for the gentrifiers to condition the people to vilify graffiti and insist on “legitimate” art without realizing that its platforms are, to begin with, exclusionary. Choi (2020) underscores: “The primary argument of those who oppose public street art, telling artists they should resort to ‘legal’ methods of art in the privacy of their homes, ignores the glaring fact that the high-end world is discriminatory. Yet, corporations have weaponized this logic to maintain control over the status quo.”

Governments react to people’s graffiti yet collaborate with corporations to put ads in almost anything. There are times when the view outside the trains is visible. On other times, barely.

Cultural worker Donna Miranda was on point in her social media post: “Takot na takot tayo sa bandalismo pero wala tayong kakibot-kibot sa walang habas na branding ng mga korporasyon sa public spaces. Ano bang mas masahol pa sa balutan mo ‘yung train ng coca cola, globe, smart, at kung ano-ano pang brand? Alam natin na public space ang tren di ba at tantamount sa institutionally sanctioned thievery ang conversion ng public space into ad spaces.” And what do people robbed of and left with almost no physical platforms of expressions get to do? Illescas in Soergel (2021) explains: “In a city where [ ] youth are marginalized, ostracized, and invisibilized, graffiti is a way for them to become visible.”

In my arts classes, I’ve always shared my deep regard for graffiti artists. Theirs is an art form that has to be performed under so much pressure—it has to be clandestine, quick, and transient due to its anti-establishment nature.

The process explains its aesthetics. “This fleeting nature, accompanied by the fact that street art competes for attention in the urban landscape, means it has to be bold, eye-catching and have a sense of immediacy,” explains Turnbull (2016).

A bamboo cart where people can give and take goods according to their needs and capacity (Community Pantry). Photo by Patreng Non

But artists couldn’t for long stay on the run, create in hiding, and work separately, as reclaiming the city is a collective duty. Initiatives like collaborative murals show how street arts could be more vibrant and inviting.

And what could be more vibrant and inviting than people’s mobilizations? A fusion of visual arts, fashion, and music, the 2019 United People’s SONA rally is one of two personal favorites.

The other one involves a single bamboo cart placed in the streets of Maginhawa which brought people back together at a time when the city couldn’t be more real than that in the window of one’s phone.

These efforts remind how the streets, despite state control, have always been there as a canvas for our shared aspirations.

*The idea for this piece developed from the author’s sharing at the UPLB Pananaw Art Forum in November 2021.

Roma Estrada maintains an opinion column for Davao Today and teaches language and literature in a science high school and arts at the University of the Philippines, Los Baños.