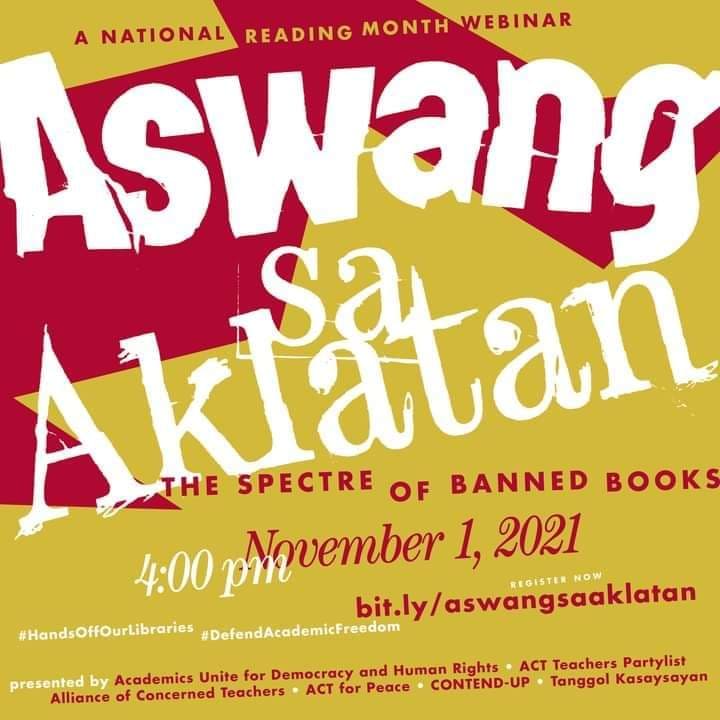

A webinar on banned books held by Academics Unite for Democracy and Human Rights on November 1, 2021

In Dark City (1998), a mysterious group known only as the “Strangers” rearranges the city as well as people’s memories at midnight while they are asleep.

To make so-called thoughtcrime impossible, words are getting erased in each new edition of the Newspeak dictionary in 1984 (1949).

Through a series of flashbacks The Handmaid’s Tale (2017) shows how the country of Gilead gradually turned into a militaristic-misogynistic society.

These stories are no longer far-fetched, or never were, given current events. Spaces are being “rearranged” while people are told to stay at home. Words and phrases like “peace talks” are being censored so thinking about them would eventually become impossible. And these are all being carried out in pocket oppressions so as not to alarm the majority and only in hindsight could they realize that these actually happened.

Last September, three state universities—that of Kalinga, Isabela, Aklan—purged their libraries of what the government labeled as “subversive” books. This is despite the current inaccessibility of most libraries, the abject condition of Philippine libraries at large, and the rampant culture of mis/disinformation from which the government itself has benefited.

A 2018 study on the status of public libraries conducted by the National Library of the Philippines reveals that most public libraries have no sufficient support and that their actual number only makes up 3% of the number prescribed by law. These findings complement the 2017 survey of the National Book Development Board that says only 1 out of 10 Filipinos aged 18 and above borrows books from libraries. These data, and the country’s reputation as the social media capital of the world, make a good recipe for the Philippines indeed being the “Patient Zero of the Modern Disinformation Era.”

Inaccessibility of information is not something new even for academics and the larger part of the world. Pre-Sci-Hub and other open access initiatives, research studies used to be exclusive only to those who can satisfy paywalls. This among other gatekeeping mechanisms of the academia and governments cost hacktivists Julian Assange his freedom for putting up Wikileaks and Aaron Swartz his life by committing suicide in 2013 after having been prosecuted for downloading academic journals from digital repository JSTOR.

Freedom of Information was one of the first executive orders signed by Duterte when he assumed power in 2016. A few years later we would find out that such freedom could be exercised only toward the information that his government wants us to know.

True to his cultural agenda, the Duterte regime doesn’t and won’t go all the way like Marcos did—except for the edifices—so he could still maintain an illusion of democracy. How could this government be accused of curtailing press freedom when it shut just one network down as it trolls another? Or of stifling free expression when it only accused a handful people of fake news for airing out grievances online at the height of the pandemic? Why would there be a need for Martial Law when there’s the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020 ever-hovering to turn any dissenter into a terrorist?

Though it may not be as apparent as it was during the Marcos era, a war against the culture of thinking is in effect and banning books from libraries is just one of the Duterte regime’s multiple efforts for which the pandemic has been conveniently weaponized. Unlike the War against Drugs, this war isn’t graphic of dead bodies in the streets, it’s almost invisible. It may as well be the entire point—to make dissent, its tools, down to its inspiration invisible and to replace it with something else.

As cops are to the War against Drugs, the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC) is to the war against the culture of thinking. As the Duterte regime’s cultural arm, NTF-ELCAC sees to it that, among many others, the public is rid of learning encounters that would lead them to analyzing the semi-feudal and semi-colonial nature of Philippine society lest they join the clamor for addressing the roots of armed conflict. Funded with billions, NTF-ELCAC carries these out through red-tagging people, organizations, and even schools as well as censoring cultural artifacts like monuments, films, and now, books with the help of the police, the military, local governments, and other government agencies.

Schools have always been on top of the Duterte regime’s cultural agenda. In 2018, the government accused a number of universities of being involved in a plan, dubbed as “Red October,” to allegedly overthrow the president. Three years later it would open 2021 with the unilateral termination of the UP-DND Accord, a 1989 agreement which aims to make the university a safe space through barring state forces from its premises. Of late, it is busy purging books out of libraries. It is becoming more and more noticeable that these efforts are actually just pretexts to create conditions that render the militarization of schools necessary.

“What’s wrong with national industrialization and workers’ rights? What’s wrong with land reform? What’s wrong with asserting national sovereignty? What’s wrong with aspiring for genuine lasting peace?” Putong (2021) asks in “Who’s afraid of books?” Us talking about it, that’s what. And if we let this go, it won’t stop in schools. It shall extend to related sectors and industries, immediately to book publishing and selling.

Whether publishing, selling, and owning books deemed to be subversive by the government would soon be criminalized highly depends on how publishers, sellers, and readers act against this ongoing censorship.

Hand off our libraries! #