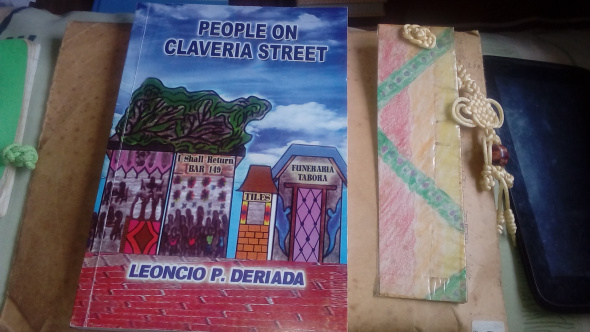

People On Claveria Street’s cover may seem clumsy and amateurish, but the book design has Deriada’s personality all over it. (Karlo Antonio G. David / davaotoday.com)

People in Claveria Street, Leoncio Deriada’s second novel, is far from his best work of fiction. But it nevertheless demonstrates the value of this living literary legend to Davao and its people.

Set in Davao City just after the Second World War, the autobiographical novel chronicles Deriada’s first few months as a boy in the city where much of his fiction is set. His family has reunited after the War, having left their hometown of Dumangas, Iloilo to join his eldest brother Gener in Davao. Much of the novel features scenes from daily life in the house of the Pagunsans (distant relatives and family of Gener’s love interest Isang), where the Deriada children are made to live to study in the city. The house is located along Claveria Street, then a quiet bajo de la campana neighborhood with mangoes, mansanitas, and cheap theaters.

The novel is chronologically set shortly before Deriada’s first novel, People on Guerrero Street, and is intended as its prequel. But unlike his National Book Award winning debut novel, Claveria Street does not seem to have a coherent plot, and it could hardly be considered a novel. There are episodic story lines featuring young Leoncio’s student life in Ponciano elementary school, his supernatural encounter in San Pedro church, his involvement as go-between in the romance between Arnold Espejo and the opera singer Crescencia Pagunsan, his experience seeing elephants in Davao, and his missing his grade four final examination. But these experiences do not seem to be fully introspected on, their human implications not polished into revelation, and overall they do not form a coherent whole. The reader is left wondering what ultimately is the point of all these narrated experiences.

The avid reader of Deriada will find this novel falling short of expectations. There is none here of the cleverness in his stories like ‘The Hunt’ and ‘Phonepal at Padre Selga Street,’ the novelty in ‘Dam’ and ‘Pigpen,’ nor the subtle but profound gravitas of ‘The Road to Mawab’ and ‘Day of the Locusts.’

Which is not to say it is entirely without its merits, for there are many glimpses of Deriada at his best in this novel. The descriptions of his first encounter with the Durian, his impressions of Calinan, and his descriptions of the Ilonggo recipes are written with the signature simplicity with which Deriada portrays the wonders of his locale without exoticizing them. His subtle reaffirmation of the Catholic faith when he encounters reading materials from the Jehovah’s Witness shows how a skilled writer renders to concise but by no means diminished concreteness a complex and cerebral theme with imagery. Where the late novelist Antonio Enriquez would choose to violently romanticize ‘the Mindanao wasteland’ in the harrowing story of Bibang, Deriada instead chooses to show the human and domestic sympathy of his mother, reducing her incident to an isolated tragedy.

But at most points one gets the impression that much of the book is the linear but random reminiscing of an old man, Deriada merely recording his distant memories before he forgets them.

That is until one realizes the value of such reminiscing. For in spite of its shortcomings as a novel, People on Claveria Street offers a rare glimpse into Davao as it once was. To the Davao old blood, the novel is a nostalgic book that harks back to the smaller and more rural Davao of their or their parents’ past. To the more recent Dabawenyo, it defamiliarizes familiar corners of the city by showing us the sheer recentness of what we know of it (Mangoes growing in Claveria!).

Ultimately, what Deriada has done is chronicle the bygone domestic history of this rapidly changing metropolis: the primate city of Mindanao is ruthlessly abandoning much of its colourful past. The episodic scenes of Claveria Street serve as historical vignettes, little reminders to Davao’s collective soul of the quaint and quiet frontier town it once was. In the novel’s preface Deriada calls himself ‘a relic of the last century,’ and with this novel he has given us a glimpse of that century from whence he comes.

Despite the surplus of wannabe Davao writers, there is in fact precious little literature about Davao. Claveria Street is only the fourth novel about the city, and of the four Deriada has written two (don’t worry about not knowing the other two, most of Davao’s writers don’t either).

And this is Deriada’s true value to the city of his childhood. No other writer has charted Davao’s literary map as he has. Most of this Palanca Hall of Famer’s large body of work deals with Davao at various points in its history and from diverse perspectives. If Davao had a diary, Deriada has written a substantial portion of it, and for all its shortcomings Claveria Street is another big part of that.

Published by Seguiban Press, the novel’s printing and layout is homely and far from sleek, almost DIY. Deriada played a very active role in its layout, with the cover illustration drawn on his instructions. Between People on Guerrero Street and the present novel, his former novel was more competently laid out, but I like this one better because it’s more colourful. It may seem clumsy and amateurish, but the book design has Deriada’s personality all over it.

Hardly anyone in Davao knew when the novel came out in 2015. As much as I try to keep myself updated with the news from Davao’s exclusive and prohibitive literary scene, even I did not hear about it. The local literary establishment did nothing to spread word about the book and make it more available (so much for promoting Davao literature). It did not help that the book was published in faraway Iloilo, and even there had a limited circulation. I only got my copy – probably the last copy available – earlier this year when my girlfriend came back with it from a workshop in Iloilo.

When I got the copy, the first thing I saw when I opened it was the preface, where Deriada, now nearing eighty, announces that he is planning to write thirteen more novels, at least five of which are about Davao. The last time I checked he was already done with another one, and it was now with the publishing house. So while I am not too impressed by this latest novel (I’ve seen him do better), it is still delightful to know that the Grand Old Man of Davao Literature is at it writing Davao’s soul down for posterity. (davaotoday.com)

————————–

Karlo Antonio G. David is a writer based in Davao. His interests include the Mindanao settler identity, the hybridization of the Filipino languages (with specific focus on Davao Filipino), and the development of local historiography and introspection, particularly of his hometowns of Kidapawan and Davao. His one-act play, Killing the Issue, won the second prize in the 2014 Palanca Awards.