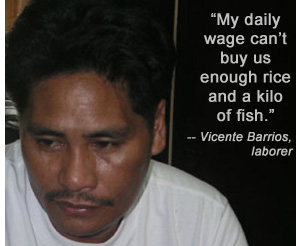

Like other Filipino workers, Vicente Barrios tries � often desperately — to make both ends meet for his family. But no matter how hard he works, he can�t get out of a destructive cycle of indebtedness, thanks to a measly minimum wage.

By Germelina A. Lacorte

davaotoday.com

DAVAO CITY � With a minimum wage of 207 pesos a day, Vicente Barrios no longer wonders why he is neck-deep in debt.

�Our daily wage could not even buy enough rice and a kilo of fish,� says Barrios, a , 43-year-old father of four who works with his wife at a banana packing plant in New Alegria, a village in Compostela Valley province, which is� known for its vast tracts of lands planted to bananas, the country’s top export crop.

�If we eat fish every day, nothing would be left of our pay,� Barrios says.

Barrios works at packing plant No. 90, also known as Suyafa Farms of the Fresh Bananas Agricultural Corporation (FBAC), where he has been packing fresh bananas for exports since he arrived here back in the 1990s.

Barrios works at packing plant No. 90, also known as Suyafa Farms of the Fresh Bananas Agricultural Corporation (FBAC), where he has been packing fresh bananas for exports since he arrived here back in the 1990s.

�There are days when there is no work at the plant, so, we don’t get paid,� he says. �But under this labor-contract scheme called pakyawan, there are also days when we had to work 13 hours straight and still receive the same daily wage.�

To survive, he would borrow money from cooperatives, which charges the rather usurious rate of between 10 and 20 percent.� He would get rice and other food items from a store and promise to pay later. He would borrow money, he says, left and right, from several cooperatives, from individuals and storeowners so that when his pay arrives at the end of the month, it would not be enough to pay off all his debts.

�When the pay slip comes, we’re always short,� he says, a wry smile forming in his mouth. �So, we have no choice but to borrow again,� thus perpetuating this cycle of indebtedness.

Barrios realizes, too, that, slowly, his family is dying. Only two of his four children are alive, as the younger ones died of strange ailments even before they reached five. One� was found to have a hole in his heart and died in 1994. Another had a kind of cancer in the blood and died in 2000.

Of the two who survived, only one — his 21-year-old daughter � managed to make it to college. The other one — a 19-year-old son — was found to have abnormalities and needed special care. They’ve all been raised in the midst of the banana plantation, where pesticides and other chemicals are widely used and are suspected of causing illnesses in people.

As workers celebrate International Labor Day tomorrow, May 1, Barrios sees the need to unite with other workers to fight for decent wage. Some of his debts have been carried over three to four years ago when he used to get paid a measly 137 pesos a day. It was only after the packing plant started forming unions last year that their pay improved to 176 pesos in July and further up to 207 pesos in September last year.

But even these increases were not enough to keep up with the increases in the prices of goods, which have eroded the purchasing power of the peso.

Ibon Foundation, the independent think tank, wrote how �the rising cost of living and low wages in the country trap more Filipino families into the mire of poverty.� According to its estimates, eight of 10 families are poor and that, based on its March 2006 estimates, the buying power of the peso had shrunk, with one pesos only buying goods actually worth �73 centavos.

Omar Bantayan, secretary-general for Southern Mindanao of the Kilusang Mayo Uno (KMU), says workers in the region are not only getting meager and exploitative wages but are also being threatened by repressive policies of the present administration. KMU, he says, will continue to press for the 125-peso across-the-board legislated wage hike, which has been left pending in Congress, and to campaign for an end to the repression of workers.� (He points out that 31 labor leaders and supporters were killed as of the year 2005 alone.)

At the Davao International Mega Gas Corporation in Bunawan, a KMU survey shows that the 212.16-peso daily wage of workers already falls 91.40 short of the average daily expenditures of a worker and his or her family, excluding taxes, loans and other deductions.

The unabated increase in the prices of commodities, which erodes the purchasing power of the peso and the real value of the workers wages, justify the workers’ demand for increase in wages, Bantayan says. (Germelina A. Lacorte/davaotoday.com)