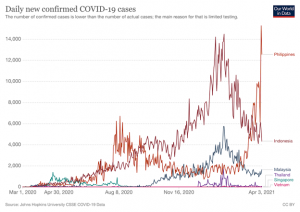

DAVAO CITY – In the last quarter of 2020, statisticians told us that the number of COVID-19 cases in the country was declining. But as the government rated its handling of the pandemic as “excellent”, cases started soaring in February. On April 2, new cases surged to 15,310, the highest reported single-day tally in the country and in Southeast Asia since the start of the pandemic.

Although the Department of Health (DOH) said this included the backlog of 3,709 cases from March 31, these figures look worse still. How did we get here and what are the ways forward?

Figure 1. Daily new confirmed COVID-19 cases in the Philippines. Source: Our World in Data

Weak health care

In an interview with AlterMidya, Prof. Peter Cayton from the University of the Philippines COVID-19 Pandemic Response Team said that there are a host of reasons that could have caused the surge. The government’s decision to reopen the economy and loosen quarantine restrictions is a primary factor.

“Mas marami nang bumabalik halimbawa sa mga groceries at larger pharmacies based dun sa huling tingin namin sa datos ng Google mobility report (Many more people have been going again to groceries or pharmacies based on the Google mobility report). This increase in mobility and interaction between individuals, or (even in the) gathering of individuals in these locations could really increase the chances of spreading COVID-19,” he said.

In February this year, the government allowed cinemas, arcades, museums, and other public venues to reopen or accommodate more people. Other measures were also implemented, such as allowing pilot face-to-face classes, allowing 75% rather than 50% seating capacity in public transportation, and allowing people aged 5 to 70 to go out of their homes.

Local governments have since followed suit, taking their cue from the national government, as reported by Rappler’s JC Punongbayan.

With weak contact tracing mechanisms and the lack of health care infrastructure, many COVID-19 positive cases may come undetected while others may not be treated immediately.

“Wala kasing nag exist na system para ma protektahan yung tao, system by government to support yung pag quarantine, so yung tao lalabas para makapag survive, para makahanap ng paraan para makapagtrabaho or kumuha ng essential goods (There is still no system that protects people, or a system by government to support people under quarantine. So people need to go out to survive by finding work or finding essential goods),” Cayton said.

Although the new variants could be another factor, Cayton said more data is needed to be able to determine the impact of new variants on the latest surge.

“[Department of Health] doesn’t regularly give updates on the new variants in the Philippines. The last report I saw is from March 15. What we are asking from DOH is to let it add the variant information on the publicly available case information data set so we can know how [the new variants] have spread,” he said.

Aside from this, Rappler noted the Philippines doesn’t yet have enough genome sequencing capacity to detect the new variants, with the Philippine Genome Center (PGC) shouldering “most if not all of our sequencing.”

Philippines vs. ASEAN neighbors

On April 2, the Philippines also surpassed Indonesia in terms of the highest recorded single-day tally in Southeast Asia since the start of the pandemic.

Figure 2. Daily new confirmed COVID-19 cases in the Philippines and its ASEAN neighbors. Source: Our World in Data

Although the Philippines shared some economic and demographic similarities with its ASEAN neighbors in pre-pandemic times, Cayton said that the Philippine government’s response was slower and less aggressive compared to Vietnam and Indonesia.

Within three months at the start of the pandemic, Vietnam developed over 100 COVID laboratories nationwide, while currently the Philippines has still not reached the 100-mark.

In contrast to Indonesia, the Philippines has also been slower in terms of vaccination and has not invested in developing a local vaccine.

In the same program, former National Anti-Poverty Commission Chair Liza Maza pointed out that the Philippine budget allocation (2.7% of GDP) for COVID-19 response is one of the lowest in the ASEAN. This is a far cry from the 13% allocation in Thailand, 20% in Malaysia, 5% in Indonesia, and 18% in Singapore.

“Anong ma-aachieve mo sa napakaliit na budget na inilalaan mo para sa COVID response? Hindi mo talaga ma popondohan yung lahat ng kinakailangan para ma contain mo yung COVID. Hindi mo ginagawa dahil you don’t have the political will to say stop itong ‘Build Build Build’ kasi ito ang kailangan natin, (What can you achieve with a very small budget for COVID response? Do you not allocate funds for everything needed to contain COVID? You can’t do it because you don’t have the political will to stop the ‘Build Build Build’ because we needed it.)” she said.

‘Lack of enabling strategy’

The government’s response to the surge is to put the National Capital Region, Cavite, Bulacan, Laguna and Rizal under enhanced community quarantine (ECQ). But the Coalition of People’s Right to Health (CPRH) criticized this as a “lack of an enabling strategy to end the pandemic.” For the health group, the lockdown alone won’t stop present surge as free testing, paid quarantine leave, and urgent ‘ayuda’ are more urgently needed.

Despite Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque’s claim that the government’s pandemic response is ‘excellent’, CPRH pointed out that the country’s 20% positivity rate is “way above the acceptable limit set by the World Health Organization of 5%, meaning the situation is really not under control.”

They also criticized the government’s ‘anti-poor’ policies.

“By limiting mobility and economic activity under ECQ, the poor and the working class are once again forced into the conundrum of choosing between livelihood and complying with public health standards,” their press release read.

“Given the pre-existing inequality in economics and health access being further worsened by the pandemic, such policies will always adversely disadvantage the poor even more; only the privileged can live and seek medical attention despite the checkpoints and fiscal crisis,” it added.

The health group further demanded that the government shift its policies towards more evidence-based decisions.

“Expecting different results with a same strategy, if not a half-hearted attempt to copy its previous efforts, is an insult to the people’s health, and must be replaced if we truly desire a way out of this health crisis.”

Asked on what would be the best way to effectively contain the pandemic, Cayton cited five ways:

- Have a national unified contact tracing system,

- Raise mass testing to 100,000 to 160,000 persons per day

- increase the number of health workers with just compensation,

- Accelerate the vaccine scheme using highly-effective, peer-reviewed vaccines,

- Conduct aggressive sequencing of the new COVID-19 variants to at least 500 cases a day.