On the other hand, the alternative or progressive theory has a rich revolutionary, radical and critical tradition that dates back to the reformist and revolutionary propaganda movements in the 19 th century struggle against Spanish colonial rule and, in the first part of the 20th century, in the armed resistance against U.S. imperialism and Japanese fascist occupation and, thereafter, in the radical and underground press of the 1970s and until today. Indeed, according to Luis V. Teodoro, former editor-in-chief of the Philippine Collegian and former dean of University of the Philippines College of Mass Communication, the Filipino press was born during the reformist and revolutionary movements, first with Marcelo H. Del Pilar’s Diariong Tagalog (Tagalog Newspaper) and later with La Solidaridad (Solidarity), Ang Kalayaan (Freedom), La Independencia (The Independence), El Renacimiento (The Renaissance) and the guerilla and underground press of the Japanese and martial law periods. “The Filipino press was an alternative first to the Spanish colonial press, then to the pro-American press that the U.S. colonial government encouraged, the Japanese controlled press, and the government-regulated press of the martial law period,” Teodoro writes. (Teodoro, “Philippine Media: Two streams, one tradition,” Bulatlat Online Magazine, August 5-11, 2001)

The progressive press therefore has a rich legacy of resisting foreign domination and fighting for independence, opposing fascist dictatorial rule and continuing attempts at reinstituting an authoritarian regime. Illustrative of this in the contemporary period of the Philippine press is during the martial law regime when writers, journalists and artists put up underground revolutionary newspapers and operated what was described as “xerox journalism” as part of the struggle against the dictatorship. They were soon to be joined by what was to become the alternative press, including the Signs of the Times which became the Philippine News and Features, the Media Mindanao News Service, the Cordillera News and Features, Cobra-Ans as well as other anti-Marcos newspapers like Malaya and the Philippine Daily Inquirer.

On the other hand, the campus press represented by such school organs as the Philippine Collegian, braved the militarization of their campuses by rallying the youth and students for the anti-dictatorship struggle even as they fought for the restoration of student councils and the reopening of school newspapers that were silenced by martial law.

These alternative and radical publications defied the repressive measures of the regime and played a key role in the events that led to the ouster of Marcos during EDSA I in 1986.

The alternative and advocacy press today can be seen in the proliferation of small publications in some parts of the country that were put up by people’s organizations, party-list groups and a number of non-profit institutions. Despite a limitation in resources, the alternative press has flourished over the past 20 years with the opening of alternative radio programs and online publications such as Davao Today, Bulatlat, Mindanao Press, and newspapers like Pinoy Weekly. Campus newspapers that classify themselves as progressive or militant also belong to the alternative press.

In contrast to the bourgeois theory, the alternative press sustains the tradition began by the revolutionary press during the period of colonialism by publishing critical and investigative reports on poverty, social injustice, political repression and human rights violations, and other sectoral and multisectoral issues. Moreover, the alternative press is born out of a society that is torn by social conflicts between the rich and poor, between those struggling for change and a few small elite resisting social transformation in all its aspects. The alternative press is alternative because it reports on issues and people who have been consistently ignored, nay, rejected by the bourgeois press and articulates the sentiments and aspirations of the poor; it is radical because it commits itself to social change and social responsibility. In a sense, it continues the revolutionary tradition of the Filipino press by its constant search and struggle for change and for siding with the voiceless and powerless majority.

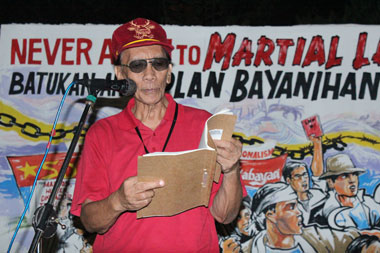

Because it advocates the theory of social change and is committed to exposing the truth, the alternative press is often the victim of political repression. Too many journalists have sacrificed their lives or have become martyrs because of their patriotism, resistance to foreign domination as well as for fighting for truth, freedom and justice. Among them are Marcelo H. del Pilar, Emilio Jacinto, Isabelo delos Reyes, Amado V. Hernandez and, in more recent times, Antonio Tagamolila, Emmanuel Lacaba, Henry Romero, Abraham Sarmiento III, Enrique Voltaire Garcia, Armando Malay, Antonio Zumel, Beng Hernandez and countless others who gave up their lives or who continue to hold the torch of the advocacy press. (Incidentally, it would be good for CEGP to publish a book or CD compiling selected writings of these martyrs as a contribution toward continuing and practicing this rich legacy of the progressive and revolutionary press.)

Let us emulate the heroism shown by these martyrs and eminent persons of the Philippine press. Let us continue to read and learn from the works and biographies of these martyrs. Above all, let us continue and develop further the alternative press � which some journalists actually call the real mainstream press � and continue to fight for press freedom in the light of what is happening to our country today. Let us continue to stand for a committed press and use it responsibly as a catalyst for social change. Bulatlat