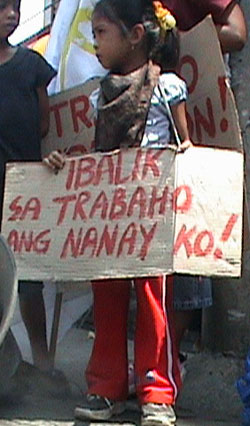

The children of the striking workers of a banana plantation in Compostela Valley have endured the same hardships and abuse their parents went through. Many stopped going to school and, because nobody would care for them, were forced to join their parents at the picketline. Several were arrested and jailed. Some are no longer optimistic about their future. Davao Today staff writer Marilou M. Aguirre reports.

The children of the striking workers of a banana plantation in Compostela Valley have endured the same hardships and abuse their parents went through. Many stopped going to school and, because nobody would care for them, were forced to join their parents at the picketline. Several were arrested and jailed. Some are no longer optimistic about their future. Davao Today staff writer Marilou M. Aguirre reports.

Related Stories: The Banana Plantations of Compostela: A History of Struggle | Banana Plantation Workers Struggle to Save Jobs | Comval Union Leader Fears for His Life | In Banana Plantations, Soldiers Bust Unions, Harass Workers | International Probers to Look Into Harassment of Workers in Davao�s Banana Plantations

DAVAO CITY — “Painful. Very painful.”

This was how 15-year-old Oliver Glen Intrepido repeatedly described his experience after he was arbitrarily arrested and detained last month together with the more than 80 striking workers at the Packing Plant 95 of the Fresh Banana Agricultural Corporation (FBAC) in Compostela, Compostela Valley Province.

The striking workers were detained on charges of contempt of court for defying a temporary restraining order (TRO). The FBAC is under the AJMR/Sumitomo Fruit Corporation, the holdings company of the Soriano family that owns some of the largest banana plantations in the country.

Intrepido recalled that a number of police, led by the town police chief, arrested and detained them at a gymnasium in Compostela for three days and two nights.

“My mother and I would take turns. While she attended to my brothers and sisters, I was at the picket line, and vice versa,” Intrepido told davaotoday.com. At the time of the incident, his mother was at home looking after his four younger siblings, one of them barely three months old.

In a psychosocial therapy session conducted by a nongovernment organization, the Children’s Rehabilitation Center (CRC), with the children of banana plantation workers in Davao, Intrepido recalled that it was the most harrowing experience in his life. He said he could never forget the gloomy faces and cries of the children, many younger than him, when they were arrested and kept in the gymnasium.

“The parents had no other choice but to bring their children with them to the picket line and to the detention area because nobody could look after them,” Intrepido said.

The four siblings of Liza Jean Estoso — aged 12, 10, six and four — were some of those brought to the detention area. Estoso’s parents had joined the strike while she was left at home with her two other siblings, one of them an infant.

“It was my aunt who told me what happened to my family. We were defenseless and felt we could do nothing but cry,” Estoso said.

She thought their future became even bleaker because of what happened. She had stopped going to school because of financial troubles. At 14, she should be in second year high school now but, unfortunately, finished only third grade.

She thought their future became even bleaker because of what happened. She had stopped going to school because of financial troubles. At 14, she should be in second year high school now but, unfortunately, finished only third grade.

John Biso, 17, shared the same fate. He was forced to quit school because his parents, both working in the FBAC plantation, could not afford to send him to school anymore. The second in a brood of five, he was worried that his younger brothers and sisters — aged 15, 13 and six — would end up like him.

Biso said he really wanted to go back to school next year but admitted that all he could do now is hope. His mother, Corazon, a member of the Nagkahiusang Mamumuo sa San Jose (Namasan, or United Workers of San Jose), is one of those who joined the strike.

Biso recalled that prior to the Sept. 26 incident, his mother had told them that if ever they, the strikers, would be arrested, they would rather spend time in jail than accept the offer of FBAC to pay the workers an amount that was way below their demand.

The mother of Jonna Achame, 13, was also one of the strikers. Achame said it would have been less difficult for them if her father had a job. He works once in a while as a canal digger.

Like most of the striking workers’ children, Achame had no choice but to stop going to school. She is the fourth of five children. She feared, too, that she would not complete her education but hoped that their youngest sibling would finish elementary.

With such young and innocent minds, they could hardly articulate why their parents were forced to join the strike and to live a more difficult life.

But Estoso was certain that her parents were correct in their stand. “They are only asking for work. If they will accept the company’s offer, the amount would only be enough to pay our debts. Worse, their back wages will not be given and would be totally forgotten. What would become of us then?” she said.

“All I know is, the company did something wrong,� Biso said. They fired our parents. They did not give the back wages.�

Because of this, Achame said, “we hardly have rice and viand. We can no longer go to school.”

Intrepido was worried for his two younger siblings. “We don’t have enough money to buy milk for them,” he said, adding that the prices of basic goods are always increasing. “My parents’ income is enough only for our food. What about our education and other bills like electricity?”

At present, the workers in Packing Plant 95 are receiving a daily wage of 176 pesos for a 14-hour work. Based on the data of the National Wages and Productivity Commission, the basic wage in Southern Mindanao for agricultural workers is 212 pesos while the cost of daily living for a family of six is 621 pesos.

Intrepido blamed FBAC for not giving just wage to his mother and the rest of the workers. “The company is too much,� he said. �In the first place, if not for the workers� help, the company would neither advance nor gain profit.”

These children might look na�ve and vulnerable, yet they believed that the struggle of their parents was just and that victory could be attained through unity. They said the constant pressure of their parents through strikes and rallies would force the company to reinstate the workers and give them the back wages and the benefits due them.

According to the Kilusang Mayo Uno in Southern Mindanao, Namasan filed a money claims case worth 3.7 million pesos with the National Labor Relations Commission for underpayment of wages, nonpayment of Cost of Living Allowance, and nonpayment of service incentive leave.

The children vowed to support their parents even if they have to join strikes every day. They hope that, in the end, they could finally attain the education and the decent life that they deserve. (Marilou M. Aguirre/davaotoday.com)