By Alvin A. Camba, Contributor/Fellow, Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

In the bustling offshore gambling industry in the Philippines today, a conservative estimate of 100,000 people work. About 90 percent of them are mainland Chinese. In this interview, a Chinese customer service worker talks about how and why they came to the Philippines; their living and working conditions; incidents of misbehavior; and how the shops run and raise revenues from operations.

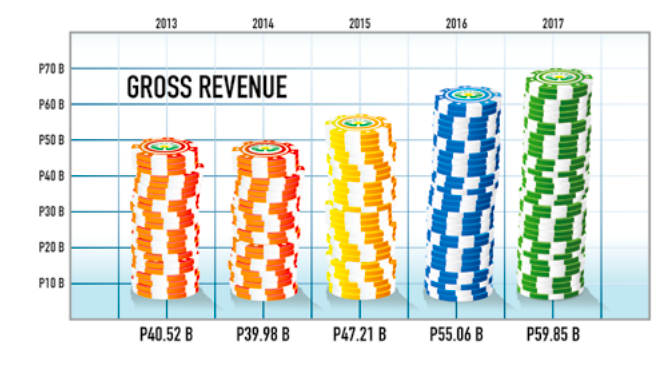

Gross Revenues of Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corp., 2013 to 2017.

Source: PAGCOR Annual Report for 2017

THE SUDDEN surge of offshore gambling firms during Duterte is not surprising. In the 1980s, the widespread inefficiency of and rent-seeking in Philippine government-owned and controlled corporations (GOOCs) limited state investment on public goods that could have reduced the cost of investing, such as energy, transportation, and telecommunications. For foreign investors, these decisions made investing in manufacturing and other productive sectors costlier in the Philippines than that of other comparable developing countries. To deal with these constraints, the Philippine government instituted new laws to attract service sector Business Process Outsourcing (BPOs) investments in the early 2000s. BPOs expediently began to employ millions of Filipinos, contribute billions of dollars to revenues, and generate forward-backward linkages across sectors.

One of the reasons why BPOs became successful was it did not compete with existing domestic businesses. Most BPO investments were offshoots of U.S. firms, which relocated their services and more labor-intensive, low-value operations in Asia. Successful foreign investments from other countries also concentrate their capital in specific sectors that do not compete with domestic businesses or provide crucial external markets to domestic businesses, such as the extractive sector for Canadians and Australians, or chip assembly for the Japanese.

Since the Duterte administration, Philippines has become the predominant home for Chinese offshore gambling investments because of cheap real estate, a booming service sector, and the state’s autonomy from Beijing. Offshore gambling originated during Joseph Estrada’s brief term as president, reemerged throughout the Benigno S. Aquino III presidency, and now has surged since Rodrigo R. Duterte took power. Similar to BPOs, Chinese offshore gambling firms target the external market, which do not threaten Philippine businesses, and instead present an additional opportunity to earn.

Offshore gambling is a booming sector because of three things. First, customers are located not only in China, but also in the ‘greater China’ area of Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. There are also reports that the Chinese across the United States and Europe avail of these services. It would be a mistake to put the blame on investors from China or Macau alone. A careful analysis of companies shows that investors come from China, Macau, and Taiwan. The workforce comprises labor from China, division heads from Malaysia, and management from Taiwan.

Second, all of these states have experienced some degree of social mobility and the emergence of the “new rich,” which means that there is surplus money that can be used. Among these states, the People’s Republic of China provides the most customers due to its massive population and the legal ramifications on gambling. And finally, Hong Kong and Macau’s offshore gambling firms were increasingly pushed out by Beijing in 2016. Because offshore gambling has also been a venue for laundering money out of China, which has led to the outflow of U.S. dollars, Beijing has begun to implement tighter regulations on the industry.

These three reasons coincided with a major change in Philippine regulations in offshore gambling. Specifically, the Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corporation or PACGOR, as a GOCC, has the power to sell licenses to offshore or online gambling companies. In the early 2000s, the Philippine private company PhilWeb signed a 13-year contract with PACGOR to sell these licenses outside the special economic zones. It was a monopoly for PhilWeb. But this was not maximized because of the company’s unwillingness to sell to the Chinese offshore gambling firms and its commitment to a business market that targeted Filipino gamblers. Since firms close to the Duterte administration realized that there was money to be made, Philweb’s contract was not renewed. PAGCOR then regained its powers to sell licenses, leading to an open market for offshore gambling firms and the uptick of Chinese business activities and services in the dataset. This move would not have been possible earlier because of PhilWeb’s close links with the Aquino administration and the possibility of a long legal battle at the Supreme Court.

Offshore gambling companies are very low maintenance. Unlike Western BPOs, they can set up shop anywhere so long as they have computers and Internet connection. Functions of online gambling include customer service, which entails talking to customers about the firm’s products, services, and games. This is similar to how Filipino call-center workers talk to U.S. mobile phone owners halfway across the world in order to deal with processing refund, hotel reservations, and other issues.

Some companies reportedly use customer service not only to deal with online gambling concerns, but also to provide service to Chinese companies that need to deal with consumers from China. There is a division on marketing, which targets the email addresses and home numbers of Chinese populations across the world, in order to induce them into playing. A gaming division exists, which comprises the Chinese workers pretending to be players in the game to induce players into playing more. A research and technology division creates new research and programs new apps. Some companies also have training divisions, which serve to train the outfit’s new workers.

At present, the offshore gambling industry in the Philippines has a conservative estimate of 100,000 people as its workforce. About 90 percent of this workforce are mainland Chinese. Some common assumptions about these Chinese workers are that they are stealing jobs from Filipinos while taking advantage of the country’s social services, and that they lack manners.

In November 2018, my research assistant and I had a chance to sit down and talk with a Chinese migrant worker in Mall of Asia. The worker is part of the customer service section in an offshore gambling outfit. The interview was done in Chinese and English. The following are excerpts from that conversation.

AC: So what can you tell me about yourself before coming to the Philippines?

CW: I grew up in Guizhou province, in Zhenyuan (镇远县 ) county. Most of the people in the prefecture belonged to Miao and Dong minority groups. We, the Han people, are the minority in that prefecture. My family has been there for generations, but my Dad was originally from Hunan, and my mom from Guanxi province. My parents were both merchants in the city, and we had a stall when I was growing up. The stall sold food slow-cooked in an iron pan, which was the specialty of the country. Tourists from the other provinces go to the county to visit the local scenery: The Black Dragon Cave and Wuyang River Scenic Area. My town was beautiful, but it was increasingly becoming more difficult (to live there). Richer Chinese from nearby provinces have started to purchase land to create small hotels and big condominiums, driving up the price of living there.

AC: Why did you decide to come to the Philippines? Why work in the gambling firm?

CW: I finished a two-year trade school that emphasized business skills. At that time, my options were to leave for the bigger cities and work for the government or companies. I left to work in Shanghai for six months as a receptionist in one of the hotels. The conditions were difficult: we had to work 12 to 14 hours a day, the salary was low, and the rent was high. I was barely saving anything, let alone able to send money to my parents. Since the contracts were not permanent, I had to be renewed every two months just to work. From there, I met a recruiter who was looking for workers in the online casinos.

There were different options at that time: Cambodia, Malaysia, Laos, Thailand, and the Philippines. The Philippines was their newest destination and offered the most amount of pay — US$2,800 (a month) — and they take care of lodging, parts of the living expenses, and migration. Cambodia and Laos were not enticing options. The demand for labor was not as high in Malaysia and Thailand. My parents were fine with the situation and understood that I needed to make money. I submitted my papers to the recruiter and came here in early 2017.

AC: How did you arrive in the Philippines? What was the route like?

CW:It’s a model that they employ when coming here. As far as I know, there are six to seven different ways. But from my experience, me and my co-workers traveled to Guangzhou and took a cheap, low-budget flight to Changi in Singapore. From there, we took a connecting flight to Angeles City in Pampanga. Immigration was rather easy. We were part of a tour group that was processed by the company way before. And Angeles City airport was full of tourist groups that were coming to the Philippines. There were mostly Koreans there. From there, we took a bus to Manila, and I remember that it was a two- to three-hour ride in the morning.

AC: What was your impression of Manila like? Or Angeles?

CW:Metro Manila reminds me a lot of Beijing without the transportation system. The traffic is worse in Beijing and you can get stuck in the roads for hours. Metro Manila seems to have a lot of small vehicles used for transportation, such as jeepneys, tricycles, and vans. Beijing and Metro Manila differ in two respects: (1) pollution is not as bad here and moving around in Manila is possible in early morning or sometimes at night; (2) it’s dangerous to move around here and crime seems to be high. In China, the government has been able to keep peace and punish criminals harshly. Here, I have never experienced any theft or robbery, but some of our Filipino staff members and Chinese workers were robbed by Filipino criminals.

In our company, it is often emphasized that we stick together when moving around Manila. We are discouraged to go to the provinces or areas that we do not know of because of the theft and the threat of criminal gangs. It is also said that we should not trust the police since many of them are involved in these robberies.

I was in Angeles City only for a day, but we stayed in this small house that was owned by a Korean who had ties to the company. It felt to me that the Koreans own Angeles City: they had buildings, restaurants, houses, and etc. Some of my Chinese coworkers were offered the opportunity to work in one of those Korean nightclubs that’s exclusive to Koreans. In fact, I remember distinctly that this Korean lady who owned the house emphasized that we don’t have to deal with the Filipinos who were the support staff or workers of the company. We only have to deal with Korean and white men, who had money and were willing to pay. Some of the Chinese migrants decided to stay there and the Koreans had to pay for their bond and their replacements.

AC: What are working conditions like? What are the pros and cons of working there?

CW:When we got there, we had to give up our passports and we were given our company identification cards instead to use around the city. We were told to process the social security and apply for the temporary work permit (Alien Employment Certificate). What my co-workers and I did not know is that our payment of US$2800 is reduced to US$648 a month. Part of the payment is used for the lodging expenses, the materials we get for necessities (laundry, food supplies, etc.) and also for the Philippine government taxes.

We work six times a week, around 12 hours a day. Our salaries are fixed for that 12 hours, but we can get paid more especially when there is a demand for overtime. Some workers also need to work every day since they borrowed money from the company to pay for some expenses in China. There are also penalties on our salary if we break the rules, such as getting in trouble with the locals or the police, traveling to other provinces or cities outside Metro Manila, or bringing locals to the office. It is very difficult since we have to be up at four or five in the morning to get ready for the six a.m. shift. After waking up and preparing, some of us take the company vehicle to other parts of the city. But for customer service, we only stay in the building and move to another floor when it’s time. For my co-workers, they need to be on the road at five in the morning. Those who are late often get a penalty fee that will be taken out of next month’s salary. There were also rules on misconduct and other related offenses. There was another team in charge of the six p.m. to six a.m. shift.

We go to Mall of Asia or Binondo on Sundays. Some of us have Monday as our free day. We enjoy eating at restaurants, watching movies, or just walking around the mall. Most of us go to Mall of Asia since the commuting is a lot easier with direct transportation from our office. But it has been very crowded.

AC: What is your daily routine like?

CW:I wake up at five a.m. in the morning to prepare for work. Our rooms remind me of Chinese dorms: we stay with four to five roommates, share a common bathroom and kitchen, and do the laundry in a central area. We get to know our workmates as well, share our concerns and origins, and strategies for coping. We also wake up very early to get ready for the six a.m. to six p.m. shift. Those who will need to work in other buildings often get up earlier. Many of us take a bath at night rather than the morning, but we do make sure to go to the bathroom or brush our teeth. There is another shift that gets around at eight a.m.

There are floors for men and women in the living accommodations. Our key cards only work at certain floors, there are cameras at every floor, and penalties for misdemeanor.

AC: What kind of misdemeanors?

CW:They involve stealing another person’s property, sexual activities, making a mess of the place, drinking in the rooms.

Sexual activities are more common. Since there are men and women working for the company, they sometimes go in romantic relationships or even just one-night stands. One of my friends got caught and they were fined US$50 each, which was taken out of their next month’s salary. Sometimes, they don’t financially fine you, but you need to do labor for the company, such as cleaning the toilets, doing extra hours, or doing laundry.

AC: Are you provided food or other necessities?

CW: We buy food from the local canteen, which is a company-owned chain with other investors. They also sell water, basic necessities (coffee, toiletries, and etc.). There is a small gym as well, a clinic, and legal services in the building. We pay them via WeChat, or it’s deducted through our monthly pay.

AC: Are payments in WeChat?

CW: The company automatically deducts a part of our expenses. Our payment can be in Philippine pesos or in yuan, and we are given a choice on how much to allocate to which currency. We often do not need Philippine pesos unless we plan to go shopping or travel in Metro Manila. I earn about US$600 a month. I save US$300 in RMB in my Chinese bank account and get the other half in Philippine pesos.

AC: How many people are in the office? What are offices like?

CW:The offices are small cubicles with around 60 to 70 people per office. There are three to four offices or departments on every floor, which deal with targeted marketing, customer service, online gaming, accounting, financial services, and long-term subscription. There is also the technological or app-development sector, and training facilities for new employees. Different companies have different models. In my company, we operate in different buildings. Customer service sections are often in the buildings where the accommodations for workers are located. App-development sections are often located to the richer parts of Metro Manila, such as Makati City and Bonifacio Global Center. These app-development divisions do not just do work for the gambling services but numerous other third-party outsourcing as well, such as financial services, consumer technology, and marketing. There are almost 1,000 employees in our building. I’m not sure how many there are in the company.

AC: Which division are you based in?

CW:I have been with customer service for a long time. I take so many calls every day from different parts of the world and often deal with complaints about our apps. I liaison the complaints with the accounting division for the reimbursement of specific expenses or deny their request when it’s doubtful. We get Chinese customers from all over the world, such as China, Hong Kong, Malaysia, the United States, and even Africa. I do want to do marketing soon, or even accounting. But promotions are often difficult and really hard to come by. We often need to work for a few years before we get promoted.

I never learned how to program, but I’ve been wanting to since programmers get paid a lot. I think they get paid twice the amount of a normal employee, while others receive higher levels of payment. Customer service or relations get paid the least.

AC: Are these co-workers from mainland China? What about the Filipino staff members?

CW:There are also Filipino shareholders of the company and their staff members make sure we get around the city well, and that we don’t get in trouble. They are in charge of making sure the building regulations and employment follow the minimum legal procedures. They often liaise with the local government and the police to resolve legal matters. We often have a number we can call to make sure that if any of us gets in trouble, we would call the person in charge to help us out.

One of my guy friends got in trouble for a fight in one of the local bars in Manila City. The police got involved and held my friend, and the person in charge came to resolve the issue. They ended up resolving the matter, which would mean that my friend’s debt to the company increased just because of the fight.

Some of their staff members sell ID cards that we can use to save the commuting trip. I did not get those since I don’t want to get in trouble, but many of the Chinese workers have to save money from commuting.

AC: How long do you plan to remain in the Philippines?

CW:I am honestly not sure. I need to pay off my debt to the company and they promised me that they will return me to China without the government filing charges against me. A few of my fellow workers have been caught by the Philippine police and sent to be extradited to China. Many of the workers have been caught, but they ended up paying the police with their savings and the charges are dropped afterwards. It seems to me that corruption in the Philippine police runs rampantly and it does not seem to work for the country well.

I understand that our presence in the Philippines has been a problem. The Philippines is struggling to develop, and it reminds me a lot of Chinese cities with rampant inequality among the rich and the poor. But the company has withheld my passport and I owe them a lot for bringing me here. I need to pay them back a portion of the salary and the living expenses along with it, which means that I will be here for two more years at the minimum. I heard from the experience of those who have worked in Cambodia that the company helps them travel and settle in their home country after paying back the debt. Some even stay for four to five years in those countries. But the Chinese government rarely pursues charges against us after we leave the country where we worked in.

AC: How has your experience with Filipinos been like?

CW:Filipinos are generally nice. I have made friends with the staff of the restaurant, the cleaning crew, and the administrative officers of our building. I understand that in the morning, when we get picked up in our company vehicle, that Filipinos have a hard time commuting because of the public transportation system’s problems. I have visited a couple of my Filipino friends and their families. It reminds me of the family-oriented nature of Chinese families and how we struggle to keep ourselves happy.

The Filipinos I have dealt with are the ones in the malls or people we talk to in the restaurant. They are often very generous and nice to us, so I don’t see a problem with Filipinos. The Chinese-Filipinos are different, and I have spoke with some of them in Binondo. They often separate themselves from us and don’t really want to relate. They also don’t speak Chinese and seem to be just interested in doing business or using us to make connections back in China.

Filipino food is also too sweet and has a lot of pork. I do enjoy Jollibee a lot but my coworkers don’t like it because it’s too bland. I wish for better relations between the Philippines and China. We are all honestly trying to survive in this world. — PCIJ, May 2019 (reposted by davaotoday.com)

ALVIN A. CAMBA is a China Initiative Fellow at the Global Development Policy Center and a Ph.D. Candidate at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. He works on the political economy of Chinese foreign capital and elite theory. His works can be found at alvincamba.com