By Elyssa Lopez

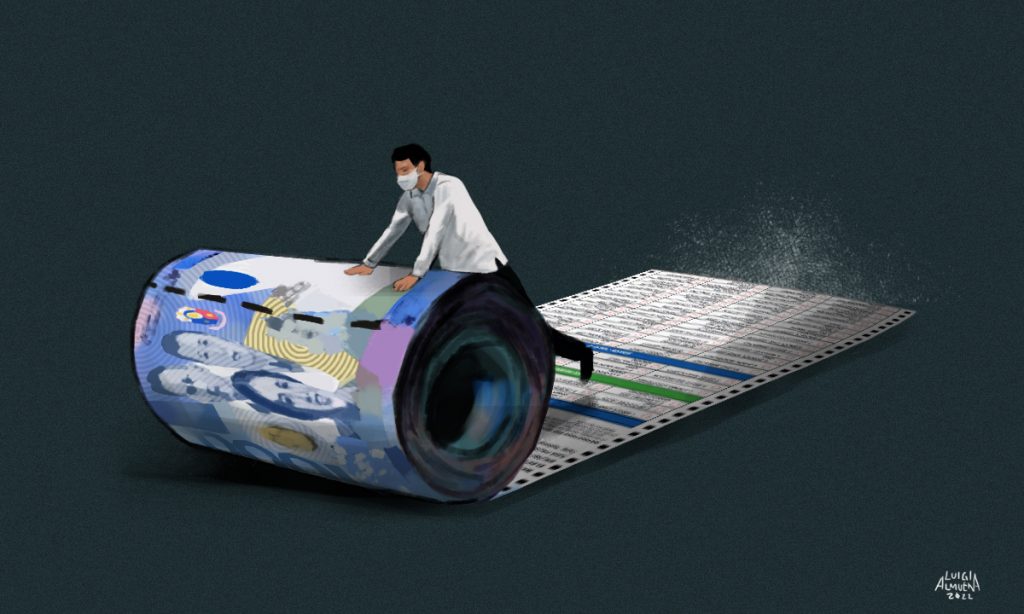

Pandemic needs, from face masks, face shields, antigen tests to additional vote counting machines and the hiring of medical personnel, jacked up Comelec’s election budget.

The 2022 elections will be the most expensive in history as the Commission on Elections (Comelec) seeks to prevent the spread of Covid-19 when more than 65 million Filipinos cast their votes on May 9.

The government allotted P38.23 billion to Comelec to prepare for and administer the upcoming elections, a Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) analysis of budget data for the years 2021 and 2022 showed.

The Comelec ranked 16th among national agencies that received the highest allocation, according to PCIJ’s review of approved agency budgets for 2022. It edged out the environment and natural resources, justice, and science departments.

Expenses for the preparation (2021 budget) and administration (2022 budget) of the national and local elections (NLE) took the biggest chunk of the commission’s budget, at 63% or about P24.1 billion. This was a 19.5% hike from the Comelec’s budget for the same items in 2015 and 2016. The amount did not include the budgets for overseas and Sangguniang Kabataan polls.

Much of the increase stems from Covid-19-related expenses and professional services fees for all workers involved in running the elections on May 9.

(For this story, PCIJ combined the budget allocations for similar election-related programs and projects listed in the 2021 and 2022 General Appropriations Act, to get the entirety of how the poll body would bankroll the May 2022 elections.)

Pandemic supplies bloat election budget

According to its 2021 and 2022 Annual Procurement Plans, Comelec requested at least P1.5 billion for the purchase of items labeled as “Covid-19 supplies.” The Comelec will provide anti-Covid supplies per clustered precinct on Election Day, including face masks, alcohol, plastic acetates, and antigen tests for election officers who would have attended trainings.

Election watchdog Legal Network for Truthful Elections (Lente) said Comelec took recommendations after the Palawan plebiscite in 2021, when gaps during the electoral process became apparent.

“What we saw in the Palawan plebiscite, kulang talaga ‘yung support staff and medical personnel deployed… But the Comelec budget was slashed… so na-retain ay Covid-19 supplies,” Lente Executive Director Rona Ann Caritos told PCIJ in an interview.

Comelec initially sought a P41.92-billion budget for 2022, but it was trimmed by the Department of Budget and Management to P26 billion, the amount approved by Congress.

Apart from Covid-19 supplies, Comelec also dedicated funds for the professional fees of national and local election workers. It increased the honorarium of election workers by P1,000 more than what they received in the 2019 polls.

At least P9.9 billion or 26% of the total outlay was allocated for professional fees, according to the budget presented by Comelec to the House of Representatives’ Committee of Appropriations in August 2021.

The election workers include the chair of the electoral board and its members, the Department of Education Supervising Official (DESO), support staff, and a medical personnel. All other election workers had been present in every election, except for medical personnel, who were added as part of Comelec’s Covid-19 preventive measures.

On Election Day, one medical personnel will oversee the isolation polling place, a makeshift room or tent expected to be established in every voting center, where voters found to be suffering from a fever of 37.5 degrees Celsius or higher may vote.

But even before Election Day, election workers were supposed to attend a series of training sessions. Comelec earmarked P4.2 billion or 11% of its total budget for these activities.

The trainings are crucial for a well-managed election, said former Comelec Commissioner Luie Guia, as the officers are the ones who will operate the vote-counting machines (VCMs) come Election Day.

“If you want your electoral board to be really familiar [with the system] you have to spend a lot… you have to have a robust training module, and have a lot of trainers,” he said.

In 2019, six in 10 Voter Registration Verification Machines, or VRVMs, supplied by Smartmatic, either malfunctioned or were not used at all. Comelec spokesman James Jimenez said those who manned the polls apparently did not remember the lessons from trainings quite well.

A PCIJ report revealed that a technical oversight of the supplier of the machines forced the Comelec to change the general instructions on the use of VRVMs, rendering training “nugatory” or useless.

Automated Election System purchases

Such mishaps have made the procurement of Automated Election System (AES)-related purchases a big story during the elections.

The poll body had initially planned to pay for the refurbishment of 97,345 units of VCMs and other consumables. But after the public bidding failed, Comelec hiked the bid price to P864 million from P600 million, which also included the lease of 10,000 more VCMs.

The additional VCMs are supposed to help the poll body set up more than 100,000 precincts nationwide, with an average of 800 voters per precinct come Election Day. This was 20% less than the average ratio of voters assigned for every precinct in the 2019 elections.

Election watchdogs have so far been satisfied with how the poll body chose to spend its budget as the whole country votes for the first time during a pandemic, even as the Comelec initially aimed to lower the average ratio to 600 voters per precinct.

“Yung elections, it could be a super-spreader event if it’s not properly managed. So ‘yung P1B allocation na ‘yan for Covid-related supplies, would still be appropriate for 2022,” said Lito Averia, treasurer of election watchdog National Citizens’ Movement for Free Elections (Namfrel).

Caritos echoed the sentiment, and found the budget to be a “qualified answer” to the need to keep voters safe from Covid-19 on Election Day.

“Kita naman ‘yung preparations ni Comelec to ensure the safety of all stakeholders in this election given the pandemic, but as always, iba ‘yung naka-budget sa implementation,” she added.

Meeting budget performance targets

The national government uses a performance-informed budgeting structure, which mandates government agencies to include the purpose of their proposed funds, from the outputs they commit to deliver to the outcomes to be achieved. Agencies must also include the cost breakdown of their programs, activities, and projects.

The poll body managed to exceed two out of three applicable outcome indicators in its 2020 budget, as part of its election administration program: an increase in new voter registrants and the cleanup of 0.13% of the database of registered voters. It fell short of the target to increase by 24.5% the number of electoral protests resolved within an election cycle, as it recorded an increase of only 22.33%.

For 2022, some of Comelec’s targets include increasing voter turnout in the three elections to be held this year: national and local elections (from 78% to 82%), barangay polls (from 70% to 73%), and Sangguniang Kabataan elections (from 65% to 85%).

The poll body managed to exceed its target to increase of new voters. As of October 2021, the Comelec has recorded 7.9 million new registered voters, about double its initial target of four million.

Revisiting the AES budget

However, as the 2022 elections is the fifth automated elections of the country, some analysts are calling for an efficient monitoring of Comelec’s AES-related spending.

The allocated budget for the development of software systems and procedures for example is P964 million. It’s a 3,485% jump from the amount spent in 2016.

“Worth asking – are we bound by a supplier? Is the supplier the one telling us what the cost should be? It can help us better understand how the digital transformation [of Comelec] is going, or if we should explore to go to market,” said Telibert Laoc, country director for Timor Leste of National Democratic Institute and former Namfrel executive director.

Laoc noted that Namfrel once lobbied for the VCM suppliers’ source codes to be open-sourced, meaning the software code used for their operations would be open for other programmers, and in turn would be non-proprietary. It failed to gain traction, however.

“There are nuances to these calls… For it to be successful, there should be a global call for VCMs’ source codes to be open-sourced,” he said.

Still, he contended that spending on AES items should be treated as an investment – a “cost we need to pay for the risk we try to avoid.”

Averia echoed the sentiment, and added how former Comelec Commission Christian Monsod used to call the elections the “cost center of democracy.”

“We shouldn’t hesitate to spend on elections because that is the time na pantay-pantay nga ‘yung citizens, especially the electorate,” Averia said. –PCIJ, May 2022

Illustration: Joseph Luigi B. Almuena

Infographics: Elyssa Lopez