By Karol Ilagan and Stanley Buenafe Gajete, PCIJ

With the Office of the Ombudsman’s latest memorandum circular, SALN access is now restricted across all branches of government.

For the past 30 years, the Office of the Ombudsman has made readily available the wealth disclosures of Philippine presidents and other government officials. Until now.

The Ombudsman, with its Memorandum Circular 1, has blocked public access as well as public inspection at reasonable hours of the SALN, for the first time since the law mandating public disclosure of these records was passed in 1989.

President Rodrigo Duterte’s 2018 and 2019 statements of assets, liabilities and net worth or SALN should have been made public within 10 days from the day they were filed. The Ombudsman initially rebuffed repeated requests by the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) to obtain copies, claiming that it was still revising the guidelines for public access to the SALNs of government officials.

More than a year since that review started in May last year, the Ombudsman finally came up with its new guidelines: the anti-corruption body is no longer allowing the public to see copies of the SALNs.

The Ombudsman circular states that copies of the SALN may only be provided to a requester if:

-

he or she is the declarant or the person who filed the SALN or the duly authorized representative of the declarant;

-

there is a court order; or

-

the request is made by the Ombudsman’s field investigation units.

Of the six SALN custodians, the Office of the Ombudsman is now among four that have the most restrictive rules in SALN access. (See sidebar: A citizen’s guide to where and how to get a SALN)

PCIJ also requested the Office of the President to release Duterte’s SALN. After all, Malacañang has made SALNs public in the past. We made the first request on June 21, 2019 and followed up repeatedly. The response? Ask the Office of the Ombudsman, which we had already done.

For the past year, repeated requests by the PCIJ for the President’s wealth statement have been tossed back and forth between the Office of the Ombudsman and the Office of the President. The issuance of the Ombudsman’s circular now essentially makes Duterte’s SALNs secret.

The latest batch of SALNs, covering the year 2019, is supposed to be filed by officials on or before April 30. But because of the Covid-19 quarantine, the deadline was extended to June 30. Once filed, these records must be made available to the public in 10 working days after filing or around July 15.

As the Ombudsman restricts public access to SALNs of the presidents and other officials, we are releasing for the first time the SALNs of all past presidents since 1989, when the law requiring the public disclosure of asset statements was passed.

These documents show that President Duterte is breaking a long tradition of presidents making their annual wealth disclosures public year after year, often even without a formal request from the press or the public to do so.

All SALNs since Corazon C. Aquino’s first statement in 1989 to Duterte’s 2017 SALN can be downloaded here. The 2017 disclosure was the second Duterte filed as president and the last that was made publicly available.

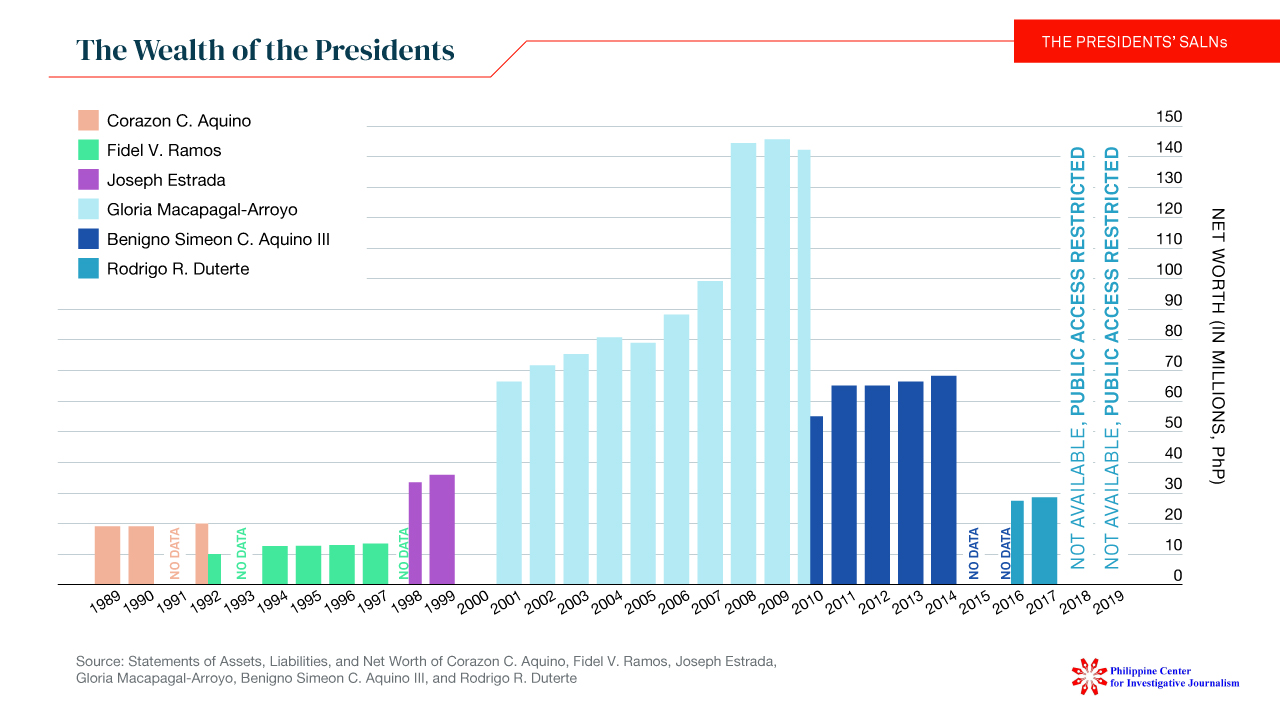

Chart 1. The declared wealth of Philippine presidents from Corazon Aquino to Rodrigo Duterte can be found in this folder. Infographic: Alexandra Paredes

Other branches of government have also become more restrictive of access to wealth disclosures. In fact, only two of the six repositories (Malacañang Records Office and the Civil Service Commission) provide access to full copies of SALNs without the need for the declarants’ approval. When President Duterte took office, he promised a more transparent government, but that has not happened.

Last year, the PCIJ published a story based on all of Duterte’s SALN filings since he was Davao City mayor. We found that his wealth increased from less than P1 million in 1998 to nearly P29 million in 2017. We also reported “big spikes” in the wealth of the president’s children, Sara and Paolo Duterte, based on their SALNs.

The president was not pleased. “What we earned outside is none of your business actually,” he said at a public event in April last year. ‘Yung may mga negosyo kami, mga law office kami — what the goddamn sh*t?”

Chart 2. In April 2019, PCIJ reported how President Rodrigo Duterte and his children, Sara and Paolo, have all consistently grown richer over the years, even on the modest salaries they have received for various public posts, and despite the negligible retained earnings reflected in the financial statements of the companies they own or co-own. Infographic: Alexandra Paredes

When we asked for the president’s 2018 SALN the following month, the Office of the Ombudsman stalled. Our request for the 2019 filing in August 2020 was also ignored until the Ombudsman released its circular a month later.

Three weeks after assuming office, Duterte signed Executive Order 2 that required the full public disclosure of many public documents. The order specifically said, “all public officials are reminded of their obligation to file and make available SALNs for scrutiny.”

Contrary to the spirit of the order and the requirements of a 1989 law, Congress and the courts have recently issued new guidelines restricting access. The Office of the Ombudsman, the uber custodian of SALNs, has changed its rules several times with varying degrees of openness.

Prior to the latest guidelines restricting public access, all requests must be approved by Ombudsman Samuel Martires. Martires, who belongs to the president’s San Beda law college fraternity, is a two-time Duterte appointee, first to the Supreme Court in 2017 and second to the Office of the Ombudsman in 2018.

Republic Act (RA) 6713, also known as the SALN Law, says that the actual SALNs should be open for public inspection at reasonable hours, available for copying after 10 working days from the time they are filed, and available to the public for 10 years from receipt of the record. These statements contain detailed information on an official’s real and personal properties, loans and other liabilities, and net worth as well as business interests, financial connections and relatives in government. (See sidebar: What’s in a SALN anyway?)

In a recent budget hearing, Ombudsman Martires said his office had stopped lifestyle checks on officials because RA 6713 supposedly set “unclear” standards.

Throughout the world, wealth disclosures are seen as an important anti-corruption tool. “The requirement that public officials declare their income and assets can help deter the use of public office for private gain,” said the World Bank. “Income and asset disclosure systems can provide a means to detect and manage potential conflicts of interest, and can assist in the prevention, detection, and prosecution of illicit enrichment by public officials.”

The SALN serves as a tool for transparency as well as prosecution as the law allows for lifestyle checks, law professor Antonio La Viña said. The wealth record offers a way to make sure that officials “do not benefit, do not increase their wealth because of their work (in government).” Through the SALN, one can track the way officials’ wealth changed over the years in which they were in power, he explained.

La Viña has reservations about everyone getting a hold of the SALNs, but said the Ombudsman circular was very restrictive when it excluded journalists from getting the records. “The media should always be given full access or at least access to the most important part of the SALN, the summary part,” he said.

The law professor surmised that the Ombudsman restricted access because the SALN had been “abused, misused, weaponized.”

To La Viña, however, those in power are the ones “weaponizing” the SALN to go after their enemies.

“President [Benigno] Aquino [III] used it against [Chief Justice Renato] Corona. President Duterte or the people of President Duterte — [Solicitor General Jose] Calida — used it against [Chief Justice Maria Lourdes] Sereno.”

The SALN was key to the ouster of the two chief justices. In 2012, Congress impeached and ousted former Chief Justice Renato Corona. In 2018, the Supreme Court removed through quo warranto proceedings Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno, a critic of Duterte and his administration’s war on drugs. Both Corona and Sereno were accused of failing to fully disclose their wealth in their SALNs.

The PCIJ has also used asset statements to hold presidents accountable for the wealth they have accumulated while in public office. Without access to the full SALNs, this kind of investigative reporting becomes very difficult.

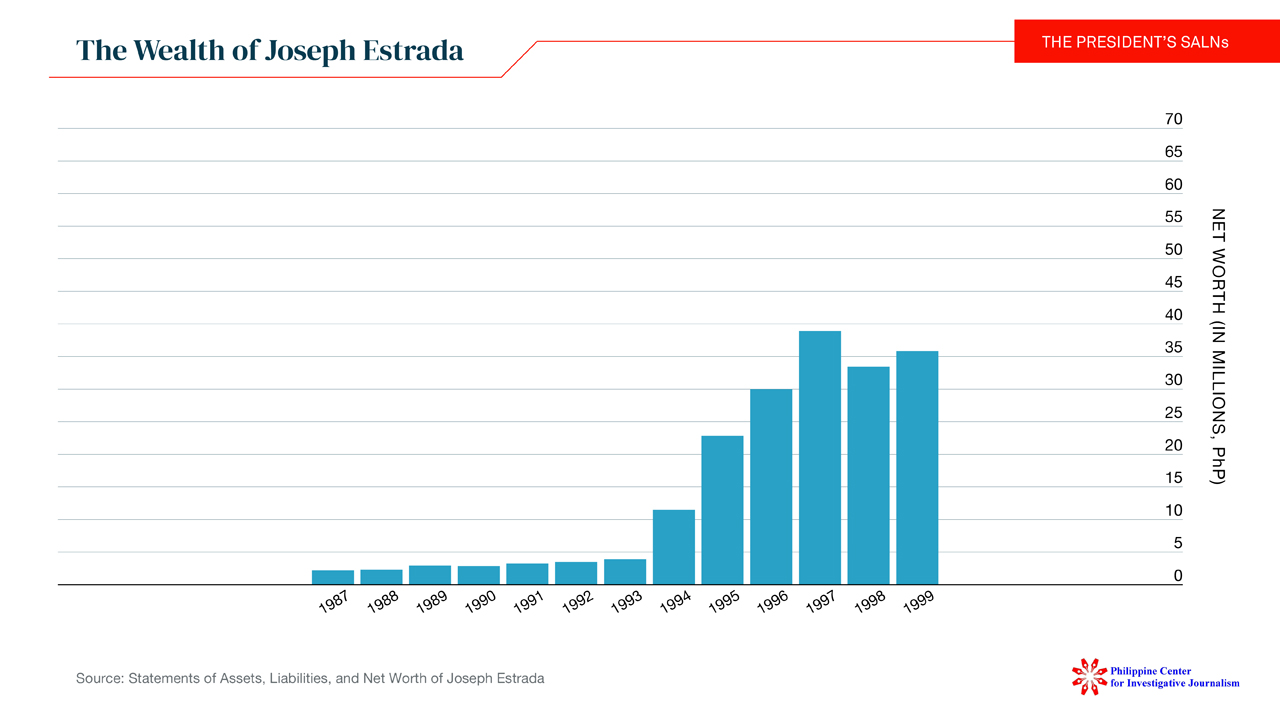

In 2000, we exposed the “millions, mansions and mistresses” of President Joseph Estrada, showing that what he had spent on his lavish lifestyle exceeded the net worth declared in his SALNs.

Chart 3. In July 2000, PCIJ reported how former President Joseph Estrada did not declare his participation in about a dozen companies in which he and his wife were major investors and board members. His wealth disclosures neither gave an idea of the magnitude of the business interests that he and his families were engaged in. Infographic: Alexandra Paredes

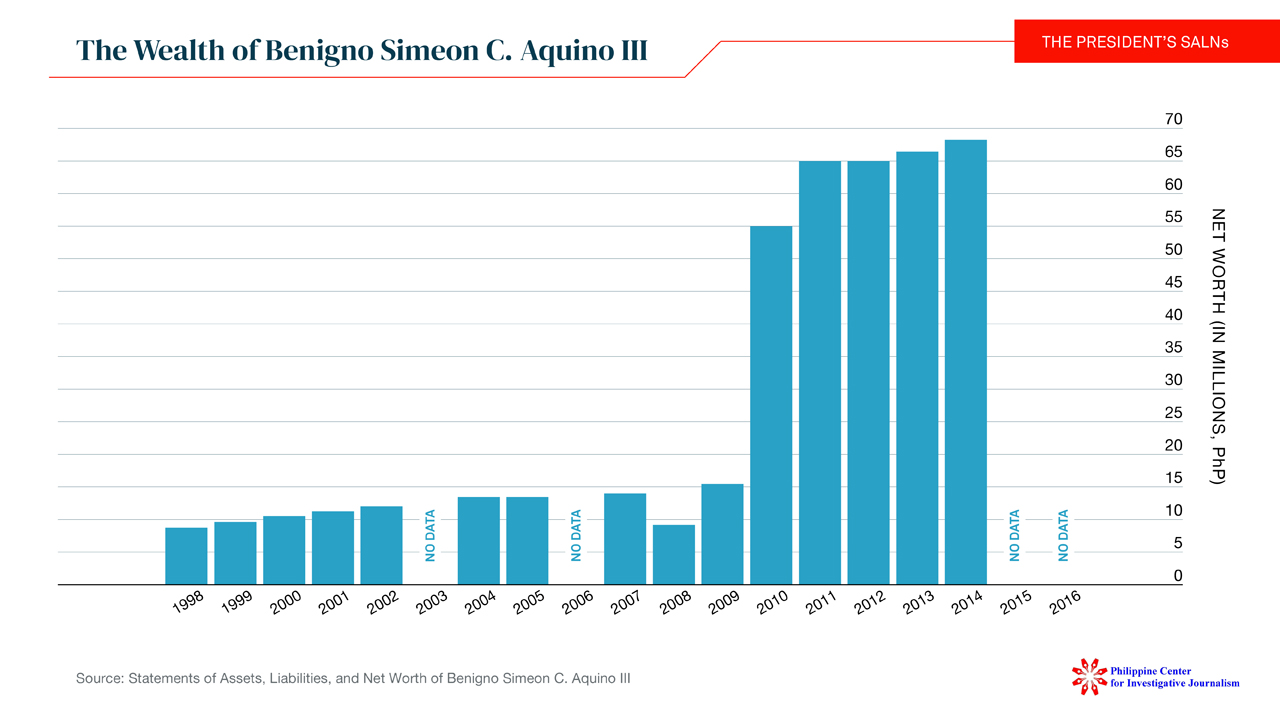

The PCIJ also reported on the murky finances of Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo in 2009 and the spike in the net worth of Benigno Aquino III in 2011. All this reporting relied on SALNs as well.

Chart 4. In August 2009, PCIJ found that the declared wealth of former President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo had increased the fastest, and by amounts much bigger, than the combined net growth of the three presidents before her – Corazon Aquino, Fidel Ramos and Joseph Estrada. Infographic: Alexandra Paredes

Chart 5. In July 2011, PCIJ reported that President Benigno Aquino III’s wealth had grown nearly three times, or from only P15.44 million as of December 2009 to P55 million as of December 2010. Infographic: Alexandra Paredes

La Viña warned that restricting SALN access to the media might increase impunity among corrupt officials. Before, corrupt officials hid illicit wealth or did not put it in their SALNs. Now, given access restrictions, they will be able to avoid scrutiny.

La Viña also said other SALN repositories might follow the Ombudsman’s lead. It’s important to file a petition before the Supreme Court to clarify access, particularly media access, he said.

In 2019, the Senate, which used to be one of the most open to making SALNs public, stopped releasing copies of the statements filed by senators. Senate Policy Order 2019-001 issued by the Office of Senate President Vicente Sotto allowed access only to SALN summaries and not the actual documents, citing the Data Privacy Act of 2012, which supposedly “restricts the dissemination of personal and privileged information.”

The House of Representatives has been disclosing only wealth summaries of congressmen since 2010. In February last year, it adopted House Resolution 2467 requiring all SALN requests to be approved by a majority vote of the House members in plenary session. Apart from numerous requirements, a requestor will have to pay P300 per SALN if the request is approved. That’s P91,500 for the SALNs of all 305 members of the House.

The Supreme Court has consistently thrown legal roadblocks at requests for the SALNs of members of the judiciary. After the ouster of former Chief Justice Renato Corona in 2012, the high court issued guidelines that required those seeking access to the wealth statements of justices to state in writing a reason for doing so. These requests also needed to be approved by the Supreme Court en banc. So far, requests from media organizations have been denied. Instead, the court releases only summaries listing the total value of the assets and liabilities of justices.

In the past 30 years, the PCIJ has obtained the full statements, not summaries, of the wealth disclosures of many public officials either through routine requests or in the course of its reporting. While some agencies held back, it was sometimes also possible to walk into the offices of government offices, or Malacañang, and get a copy right there and then. Some presidents, like Fidel V. Ramos and Joseph Estrada even disclosed their income tax returns.

The legal requirement to file SALNs is found in RA 3019 (Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act), the 1987 Constitution, and RA 6713 (Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees). (See sidebar: Laws governing wealth disclosure)

The earliest of these laws, RA 3019, enacted in 1960, requires public officials to prepare annual statements of assets but does not require that they be made available to the public. Public disclosure was mandated by the 1987 Constitution for the highest officials of the country, and in 1989, RA 6713, for lower-ranking officials as well. –with additional research by Floreen Simon, Arjay Guarino and Rex David Morales, PCIJ, October 2020

corruption, Davao City Mayor Rodrigo Duterte, duterte, Duterte SALN, freedom of information, governance, ill-gotten wealth, investigative journalism, investigative reporting, Ombudsman, PCIJ, Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, philippine politics, President Rodrigo Duterte, Statement of Assets Liabilities and Net Worth, transparency, unexplained wealth