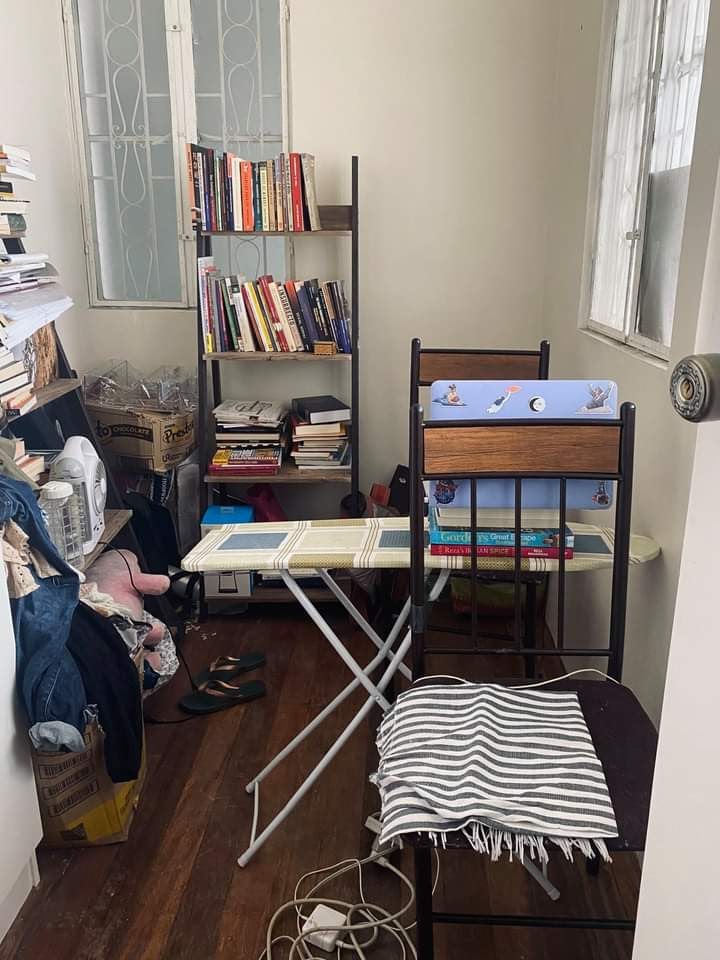

Iron board as makeshift work desk. Photo by Neen Sapalo

Unless your place already has a study, which is highly doubtful if you belong to low-to-average-income earners in the Philippines, working from home must have felt like, at some point, preparing for a play production. The stage would have to be a claimed spot from the already limited space, including those captured in the four corners of the virtual meet. If you are not into virtual backgrounds, you would have to make it look like—and sound like!—a decent office where you are supposed to be doing passionate work. Curation is key: move things around, shut other people out of the “stage”. Let the performance begin.

“As a Matter of Stilling”, artists group Pedantic Pedestrians’ online project, captured the need for a discussion on workspace in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic through their call for work-from-home photos in mid-2020. Beyond the submittables and the inputs we pitch in during meetings, what really happens while we work from home? Most of the pictures submitted for the online project expose the undeniable—an employer-issued desktop too big for the work table, portable tray tables squeezed in bed, an iron board used as a makeshift desk, even a hospital bed as workspace. Mine is that which shows a portable tabletop placed opposite the only decent background I could have displayed on screen—a white wall near the door where nothing is hung and nobody passes by, unless the device gets slightly shifted. I could turn to coffee shops like I used to, except that nowadays most of them are either shortening dining time and operating hours or withholding access to basic facilities like the toilet. Had the pandemic happened in 2018, back when I was still living with family, my workspace would have looked like this: the lower part of a bunk bed with a desk on the side. There were seven of us occupying an estimatedly 3×3-meter studio apartment and at the height of the pandemic, I couldn’t help but think: what if all these happened three years ago?

Suppose we are able to make our tiny workspaces at home appear decent enough, these weren’t meant for work to begin with. Facilities that make spaces conducive for work remain in the actual offices while the resources, especially electricity and internet, supposedly paid for by the employers, are instead being shouldered by employees themselves. This reminds me of Worry-Free Corporation, a fictitious company from the film Sorry to Bother You (2018) where workers supposedly don’t have to worry about food and housing because the company got these covered through rationed meals and bunk beds. Reversedly, in the current setup, employers no longer have to worry about providing workers conducive workspaces as the latter’s own household got these covered. It could even be that they no longer have to worry about pretending to provide reasonable salaries since one is supposedly lucky to even have a job in the middle of this pandemic.

In the essay “Estranged Labor” (1844), as though having seen far ahead into the future, Marx discussed the inverse relationship of working and feeling at home: “He [worker] feels at home when he is not working, and when he is working he does not feel at home.” What happens now that middle-class labor has shifted to the work-from-home setup? A student in one of my classes has put it quite accurately: not only have we been long alienated from work, we are also beginning to get alienated from home. Because work-from-home setup compels us to perform both official and domestic labors in the same space, we end up confused and fragmented, estranged from our colleagues and even from our own family.

The pandemic hit on my tenth year of teaching and this meant that I punctuated my first decade in service through Google Classroom and Google Meet. Though teachers were issued laptops for the online distance learning the school has adapted, I opted to host synchronous classes on my phone. Without postpaid wifi, I was connected only through data. Some virtual meet functions had been unavailable on the phone but I seldom got disconnected. Other teachers weren’t as lucky. In Where We Are: When the Storm Comes? (2020), a Gantala x Bar de Force Presses online exhibit documenting everyday life and feminist responses to being locked down, Professor Neen Sapalo displays receipts of struggle with online distance learning—screenshots of prepaid load, of online notices of class interruptions, as well as a photo of her makeshift desk. My share of improvisation would have to be a pile of books on the portable tabletop, on which I place my phone through a portable stand. This was an attempt at the eye-level angle, though I am quite certain I still appeared as though looking down on the screen. Also, there’s one expression I’ve said more than enough throughout the year, something I asked each time I called a student to speak: “(Name), are you there?”

But beyond the concerns of connectivity and curation, how has this hopefully temporary migration from physical to the virtual space impacted teaching and learning? For decades schools have tried to provide a conducive learning environment through assigning particular spaces for different areas of study—the playground, the gymnasium, the music room, the science laboratory, the library, the theater, and so on. Have these facilities had an equivalent in the virtual space or has the latter rendered them irrelevant? For a long time too, physical schools have at least levelled students of different backgrounds. This attempt disappears in online distance learning where students’ learning is determined by how spacious their houses are, which device/s they use, what kind of internet connection is available to them.

It is equally curious to know how this sensory-deficient, two-dimensional setup affects memory, not just of topics for learning but of the experience of learning itself. There is a tight connection between physical spaces alongside the sense experiences in those spaces—sight, sound, smell/taste, touch—and memory. How would students and teachers alike remember the past school year? Especially for the seniors who just graduated, what kind of memories will they take with them to college and for the rest of their lives?