Black and White photos have always amazed me long after it was not in style anymore. In the early days, I would be glued on any photo book that showcases images in black and white, even those that have seen better days. For me, these pictures are precious gems more than even diamonds because they hold an evidence about the past.

That’s why I admire photojournalists and would have wanted to be one, but then I have to be content with what I have and celebrate some of my close friends who have lived their full potentials as masters in their craft as photographers.

Photo by Medel Hernani

Unassuming in all his simplicity, I have known Medel Hernani whom we have fondly called “Boy” as the light-footed and quick photographer of the Development Education Media Services Foundations (DEMS) in the early eighties, whose work not only involved capturing images during Martial Law, the height of protest actions in Davao. Boy, now at 70, remembers that DEMS was where he was given the opportunity to grow to become one of Davao’s finest photojournalists. “Pinaagi ni Vir Montecastro ng maoy naghatag ug higayon nako nga makat-on ko sa photography, diin gitudloan ko niya diha sa correct light exposure, sharpness sa subject, ug hangtud na sa dark room, sa pag-develop sa mga film to negative, ug pag print sa mga hulagway,” he recalls. (Through Vir Montecastro, who gave me the opportunity to learn photography, who taught me the correct light exposure, sharpness of the subject, but all throughout the process of developing the film into negative and then finally in printing the pictures.)

After covering rallies, or going to some difficult assignments during the height of Martial Law, Boy would then go to DEMS’ darkroom to process the rolls of films. After a matter of hours, he would then hang the still-wet photos in the red-lighted room darkroom for the meticulous eyes of DEMS’ once master editor-mentor and most revered photojournalist\trainer Virgilio “Vir” Montecastro, who had the perfect eye for the best image.

For years, this was how Boy masterfully developed his skill in photography, always with a bucket full of patience and perseverance starting from the planning stage before covering events up to the time that he had to produce and present his black and white copies. Always with utmost care and mindfulness to details like the exact light and timing in capturing “the moment”.

Another friend and colleague in Media Mindanao News Service (MMNS), Diomedes “Brady” Eviota likewise said, “Medel ‘Boy’ Hernani remains one of the photographers I look up to. Not because I am a fellow photographer (I am not) but because of the dedication, respect, and passion that he gives for journalism and the art of photography. I grew close to Boyax, as we fondly call him, as members of the Media Mindanao News Service or MMNs, an alternative news agency in Mindanao. Boyax then was the senior and head photographer of MMNS.”

The perfect capture in black and white

The stark reality as projected in human faces and even the tense situations were unmistakable in many of the black and white images churned out by Boy’s searching eyes and lenses, such that even if the situation had happened from the past, the photos seemingly still bring the viewer that feeling of looking at the scene in the present time.

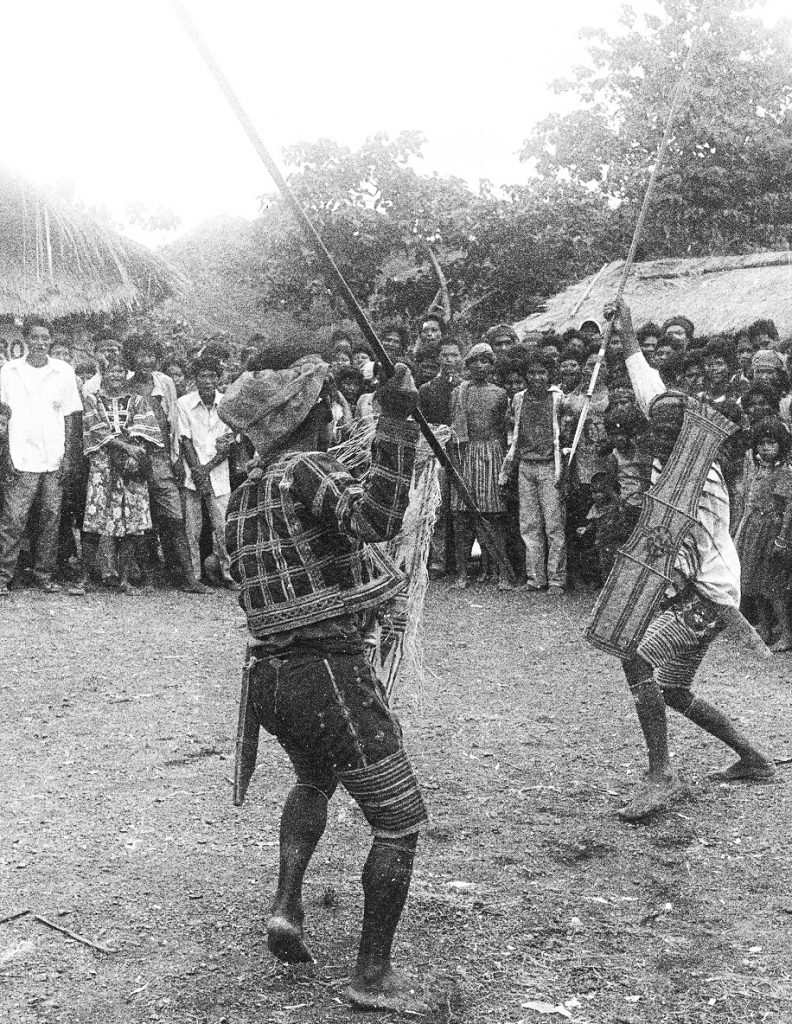

Photo by Medel Hernani

Some of these images were those of the Indigenous Peoples living in dire poverty up in the harsh environs of Talaingod, in 1994, when Boy was among those who joined the Relief and Fact-Finding Mission conducted by Human Rights groups and other non-government agencies working with the religious groups in Davao City.

Photo by Medel Hernani

Having been raised and grown into an impoverished family himself, who had to survive on sparse income in the so-called squatters’ (informal settlers) area in Bugak, Sasa, Davao City back when he was little, Boy had known what it was to be hungry and destitute.

Growing in an environ of hard knocks

The discipline must have grown into him at a very young age, when Boy had worked to earn his keep and helped his impoverished family earn a living by whatever means, like washing abaca fibres when he was still very small and could barely lift a heavy load. Much later as he tried to continue his studies after his parents could not support him, he worked his way persistently up and determinedly finish his college degree at a local university.

Hence, when he joined an alternative media outfit in Davao City, the Media Mindanao News Service (MMNS) in the early 90s after most established media had been shut down through the years following the declaration of Martial Law of then President Ferdinand Marcos Sr., the difficult coverage in the city outskirts had proved his mettle.

One memorable coverage happened somewhere in Surigao, together with a team composed of writers and some religious groups who were approached by families of the soldiers who became prisoners-of-war or (POW) by the New Peoples’ Army (NPA) and were due for release at that time. Boy recalls that it was the most difficult coverage he had ever experienced as a photojournalist.

The team was brought by a guide who knew about the area where the POWs were. For Boy, it was a harrowing and nerve-wracking experience as he was filled with dreaded thoughts of getting hit in the event of a crossfire, even as walking through dense foliage and difficult terrain for hours on end made him wonder if he would still come out alive after the assignment.

Then, before he knew it and after several hours of endless trekking, they finally came upon the soldiers held by the rebels. Though he could no longer recall their names, he could not forget what he saw, and that was the camaraderie that seemed to have developed between captors and captives.

“Nakita nako nga managhigala na ang mga sundalo ug NPA nga maoy nag gwardiya nila. Sulti sa labaw sa mga sundalong na pow maayo ang pag tratar sa mga NPA sa ilaha.” Dihang na print na nako ang mga photos, makalipay tan-awon nga maayo ang relasyon sa mga rebelde ngadto sa mga sundalo. Ang realization nga bisan lisud ug delikado ang maong coverage, apan kabahin ko sa grupo sa pagbuhi sa mga sundalo nga na POW.” (I saw that the soldiers and the NPA seemed to be friends already. Even the leader among the soldiers told us that they were being treated well by their captors. When I saw the prints of my photos, it felt good to see the seeming good relation between the soldiers and the rebels. Thus, even if it was the most dangerous and difficult coverage I’ve ever experience, I was happy to be part of that team that saw the release of the soldiers.)

Through the years though, nay, decades that he continued to document through his lenses the different life events among the very least, the workers and the realities among the urban dwellers where he started, Boy said it seems like the years have come and gone and nothing significant has really happened since then.

“Murag wa pa mo sink in sa akoa nga upat na diay ka dekada kong nag coverage, pag capture sa kalisud nga gibati sa mga mag-uuma, kay hangtud karon mao gihapon ang ilang kahimtang. Ubos ang ilang produksyon, ubos ang presyo sa palit sa ilang abot. Ug walay yutang matikad. Ang mga lumad, ata Manobo sa Talaingod hangtud karon nagpadayong adunay hulga sa ilang kinabuhi aron lang ma depensahan ang yutang kabilin batok sa mga gustong moilog niini,” he sadly reflected. (It seems like the four decades that I have been covering and capturing the difficulties of the farmers have since passed but their situation still remains the same today. The farmers are still suffering with low production in the farms that are being bought at low prices, and on top of that, they still do not own a land to till. Likewise, the indigenous folks, the Ata Manobo in Talaingod for instance, are still being confronted with threats against their lives as they continue to defend their ancestral lands against big land grabbers.)

As senior photographer of Davao Today in the later years before he slackened his pace in coverage, he consistently shared his passion to his young colleagues, one of whom is his son, Jose, who is following Boy’s footsteps as photojournalist.

WOMEN’S PROTEST. Lumad women join the call to lift Martial Law in Mindanao following the end of the Marawi crisis in a protest held at the Freedom Park in Davao City on Friday October 27, 2017. Organizers said the protest is in line with their commemoration of the National Women’s Day of Protest today, October 28 which started in 1983 as an anti-Marcos protest. (Medel V. Hernani / davaotoday.com)

Still, he hopes that through the images that he painstakingly captured through the years, people will remember and that the next generation will learn the struggles of so many Filipinos who have been living on the fringes of society. With the help of well-meaning friends and acquaintances that he has worked with through the years, Boy hopes to contribute to the current efforts among historians, writers, and advocates of human rights to defend and preserve historical facts that are being threatened by disinformation and fake news trolls nowadays.

Margarita Valle is a mother, veteran alternative news writer and development worker, whose passion is to write stories of the Mindanao Lumad and women in their quest for social justice. Her previous column is called Kanak gamay na kyatigaman (My little understanding) under her maiden name Fides Avellanosa.