DAVAO CITY, Philippines – Protecting the environment has been a risky endeavor in the nation, but a joint program by environment groups has fielded about 300 local indigenous peoples and farmers in Davao to protect the city’s watershed and forests and has yielded results in the past twelve years.

Bantay Bukid is a program overseen by Interfacing Development Interventions for Sustainability (IDIS), the Philippine Eagle Foundation (PEF), and the Euro Generics International Philippines (Egip) Foundation, which was started in 2011 by the former two groups after they partnered in a program to protect the Talomo-Lipadas and Panigan-Tamugan watersheds.

In twelve years, Bantay Bukid has augmented the limited personnel of ten persons from the Department of Environment and Natural Resources Forest Protection Unit in charge of the city’s three districts.

On an early Friday morning, Nilda Landim, 51, one of the five female Bantay Bukid volunteers in Barangay Carmen, Baguio District, joined an expedition to Sitio Kalatung, Barangay Tawan-Tawan to validate their previous reports on the alleged illegal construction of roads and infrastructures of settlers in their ancestral land.

Despite her age, Nilda, who belongs to the Obu-Manuvu tribe in the community, is able to trek with the team as the pickup trucks struggle to traverse the stiff and rocky roads going to Kalatung. She is used to walking long hours up the mountains as Bantay Bukid volunteers have the exceptional tasks of conducting foot patrols to monitor key wildlife species, watershed monitoring, and rain forestation activities to help reforestation of upland and riparian forests within the watershed areas.

Nilda had volunteered in 2014, to protect their tribe’s ancestral domain that spans 7,758 hectares. They have opposed a self-proclaimed chieftain of datu who has sold the area in an adjacent area of the barangay of Tawan-Tawan where Kalatung is situated, and structures are now growing there like mushrooms.

“Dili mi gusto nga among ancestral domain mabaligya kini kay sugod sa sinugdanan, 1938, ang among apohan naa na gyud dire bukira,” said Landim who is married to the tribal chieftain. (We don’t want to sell our ancestral domain because our forefathers lived here since 1938.)

“Legal” encroachment

Kalatung was once a lush mountainous site especially when it was then a New People’s Army (NPA) territory. Bantay Bukid volunteers and the NGOs even attest that the presence of the armed guerrillas before preserved the mountains as it staved off settlers from cutting trees or building houses.

But now, the area is affected by deforestation, road widening projects, construction of houses, and private-owned facilities, a report from EGIP Foundation says. In 2018, the Obu-Manuvu tribe in Carmen, supported by the Davao City Environment and Natural Resources Office (Cenro), wrote to the city government of Davao to raise concerns about these encroachment activities.

Bantay Bukid also filed a case in court with the help of DENR, the Carmen LGU, Davao City Watershed Management Council, and the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) – Davao but the case was dismissed in 2019, which paved the way for people to own the land.

Now, there are 130 settlers in the area, who reportedly pay monthly dues of ₱ 100 to 200 to the “self-proclaimed datu” who promised them they could own two hectares of land.

The expedition guided by Landim was led by city councilor, Temujin ‘Tek’ Ocampo, head of the council’s environment committee. Ocampo, a former television broadcaster, said he heard of these allegations before.

“Natingala ta nga layo na kaayo to sa syudad pero naay kalsada and then naa nay mga nakapaskit nga no ‘trespassing private property’ considering that the area is protected under the Watershed Ordinance nato. Natingala ta nganong daghan nang mga kakahoyan nato ang gipamutol, naa nay mga rest house, dunay mga prefab nga mga balay inshort daghan nay mga migrants ang naa didto,” said Ocampo.

(It’s surprising that we are far away from the city yet you see there are paved roads, and there’s a ‘no trespassing, private property’ sign considering that this area is protected under the Watershed Ordinance. I’m shocked to see many trees cut down, there are now rest houses, prefab houses, there are so many people migrating here now.)

Ocampo talked to settlers and learned that they were asked to pay ₱9,000 each for survey fees, but later they were only provided 130 square meters of land.

Tribal legacy

The Obu-Manuvu tribe will wait for the city council’s next move after Ocampo’s visit. For now, they continue with their mission to protect their land.

Accompanying Nilda is her son Francisco, Jr, who has been a forest guard since his teenage years, and is now team leader of the Bantay Bukid volunteers in Carmen. He grew up watching his father trek through the forest to monitor the illegal cutting in the mountains, this was way before the Bantay Bukid program was formed in 2011.

Most of the volunteers in Carmen are tribe members and relatives of Landim Jr, as they said it is their duty to secure their livelihood and identity as passed down by their elders.

“Sa wala pa nang Bantay Bukid naga bantay na mi naga monitor na mi kay tungod sa kinaiyahan nga kabilin sa among katigulangan sa una pa nga nasunod sa akong papa hangtud na pud sa akoa karon nga dili namo gusto nga mapasipad-an ang amoang erya,” said Landim Jr.

(Before Bantay Bukid was created, we were already keeping watch and monitoring the land, because this is what our forebearers left us. My father carried on this task before and now it’s mine, that we don’t want our area to be abused.)

A Datu’s mission in Marilog

Meanwhile, In Davao’s Marilog District, another group of Obu-Manuvu tribe has begun its work with Bantay Bukid.

Datu Leonardo E. Man-omanan, 63, recently became a volunteer this month through a “Deputation Training” along with 80 other Lumad.

The deputation training is required by the government to deputize and accredit Indigenous Bantay Bukid volunteers to have legal authority to confront timber poachers, treasure hunters, forest violators, and non-IPs who encroach into their ancestral lands.

Man-omanan’s community in Sitio Mahabok, Barangay Marilog, witnessed how logging companies owned by Sarmiento, Robillo, and Alcantara cut down their forests since the 1970s, and the deforestation has caused flash floods and landslides.

Many birds and forest animals have become endangered or extinct, putting at risk a natural treasure that Man-omanan once wished to protect during his younger years.

“Nag-abot ang logging sa una, sitentay dos. Presko pa gyud ang lugar dire, mga dagku pang mga kahoy. Wa pa gyud mga unsa diha, ang hayop kaning mga baboy, binaw naa gyud sa sulod sa kalasangan mao na ang nakita nako sa unang panahon. Nag-abot nag logging, wala na ang mga binaw, gamay na lang kaayo karon ang nahibilin, apil na mga kalaw, mga alimokon, ug bisan unsa pang hayop gamay na lang,” the Datu recalled.

(The logging companies came in 1972. This place still has fresh air, with huge trees all over. They were not here, and I could still see wild boar and deer running going through the forests. When the loggers came, the deer disappeared, only a few of them were left, even the birds, big and small, and even the animals, only a few are left.)

Marilog’s forest reserve spans over 11,102 hectares but it faces threats from the growth of residential and mountain resorts, logging, and conversion for cash crops.

What frustrates the Datu is how several illegal loggers continue to cut down trees in their forest even though it is strictly prohibited by the government.

The Datu is aware that many of his tribe members are not familiar with the laws prohibiting logging on their ancestral land. Joining Bantay Bukid is his last resort to ensure the protection of the community’s remaining forest even though he is too old to do so.

“So amo gyud bantayan karon ang kalasangan. Kami magtanom pud mig kahoy kay aron magbalik gyud ang katabunok sa kalasangan,” he said.

(We are going to watch over the forests. We will also plant the trees so the forests will grow back.)

Man-omanan hoped that by setting an example, the young generation of their tribe would do the same to save the mountains.

Threats

To protect the 244,000 hectares of natural heritage, resources, and watersheds of Davao, the forest guards of Bantay Bukid had to endure hardships of patrolling the mountains, including facing threats they usually get from the encroachers.

“Naa mga panahong nga magpatrol me kinahanglan namo hubuon anga among uniform aron di mi mailhan nga mga Bantay Bukid mi, para lang gyud maka agi mi nga luwas,” said Nilda. (There are times that we have to take off our uniform so they won’t recognize us as Bantay Bukid, and that we can go around safely.)

Ocampo said his committee had received reports of harassment against the volunteers and would include this on his on-site investigation report.

“Duna lagi mga hungihong nga these people are armed, naa daw armas and syempre kung adunahan ka duna kay capability to have the firearm para idepensa sa imong ginaclaim nga luna. So, part na gihapon sa among pagsusi kining ingon ani nga sitwasyon. Naluoy ko aning mga Bantay Bukid kay sila man ang mga frontliner diha,” he said.

(They claim these people are armed, when you have firearms that means you have money, you have the capability to have the firearms to defend the land that you’re claiming. That will be part of our investigation of this situation. I am concerned about the Bantay Bukid [patrollers] as they are the frontliners.)

What puzzles the councilor is how encroachments continue even if the military has checkpoints in the area.

Support from LGU

Forest patrollers also endure harsh weather conditions while doing mountain patrols, which sometimes can be life-threatening.

“Lisod ang magpatrol sa bukid kay paspas nagabag-o ang panahon. Naay mga higayon nga kalit na lang mudako ang tubig sa sapa, naa pud panahon kalit na lang mukusog ang hangin,” Landim Jr said. (It’s difficult to patrol the mountains as the weather can suddenly shift. There are times when the river overflows, there are times when the suddenly swoops in.)

Landim Jr. remembers vividly during one of their mountain patrols, the wind suddenly became strong like a tornado. This made it challenging for his team to find shelter for the night. Then later, heavy rain caused landslide and flashfloods, which terrified him. Without proper equipment, they relied on their own means to make it to the night.

Such situation prompted Bantay Bukid organizers to realize the need for proper protective equipment. The Philippine Eagle Foundation launched a crowdfunding campaign that raised P600,000 for the equipment of all forest guards.

In 2017, Mayor Sara Duterte instructed the Public Safety Security Command Center and Watershed Management Council to partner with IDIS and PEF in developing the guidelines for the Bantay Bukid Program including the allotment of a Php 2,000 monthly allowance which was later raised to P3,500.

The city government has also addressed some of the concerns through financial assistance programs and equipment upgrades but with the growing number of forest guard volunteers, there is still a lot needed to sustain this program.

Contribution

But amidst the adversity, Bantay Bukid has also gained a lot of fruits of their labor.

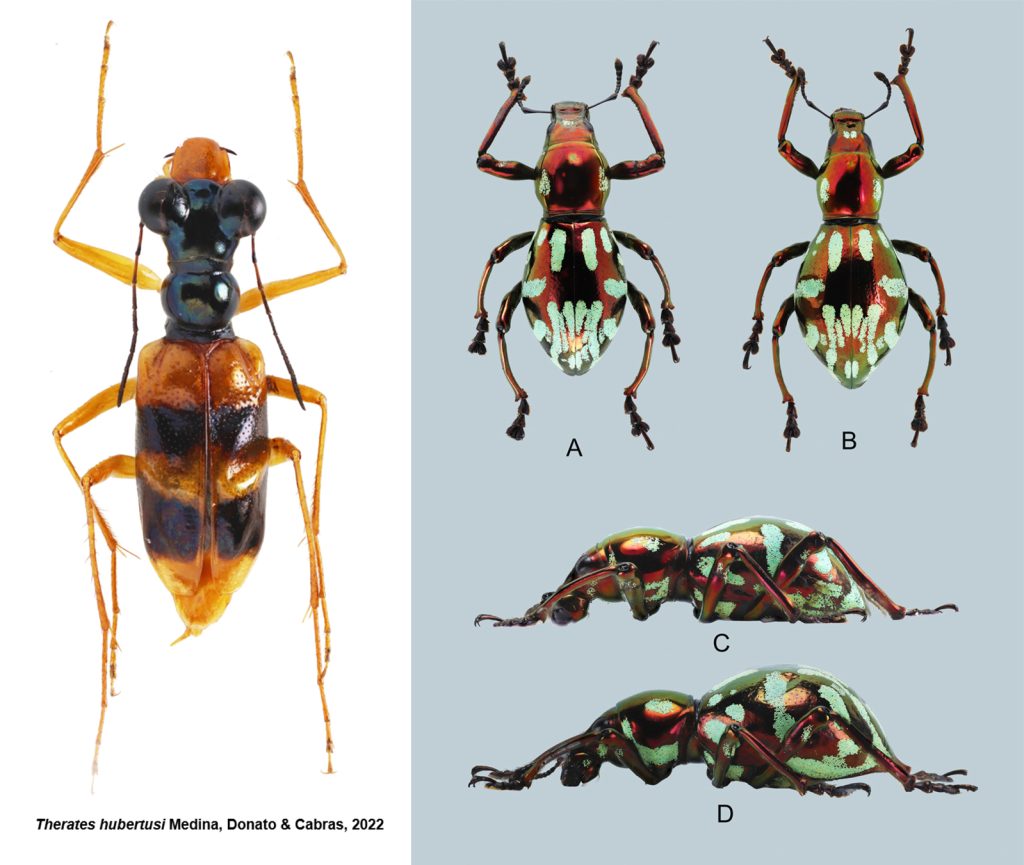

In 2022, Bantay Bukid was instrumental in the discovery of endemic beetles namely: the tiny tiger beetle, (Therates hubertusi), named after Dr. Hubertus van Dierendonck, CEO and founder of EGIP Foundation Inc., for his contribution to the conservation of the ancestral land of the Obu-Manuvu people in Davao City; and the colorful eastern egg weevil, (Pachyrhynchus obumanuvu)-named after the Obu-Manuvu tribe with its colors resemble the colors of the tribe’s traditional garments.

“These discoveries not only mean the advancement in the knowledge of Philippine Coleopterology but also showcase the conservation efforts done by the Obu-Manuvu Bantay Bukid and the whole tribe together with EGIP Foundation Inc. and other partner agencies in preserving their ancestral lands and wildlife that naturally thrive in the area such as the species of beetles,” EGIP Foundation statement.

IDIS also noted that Bantay Bukid volunteers recently apprehended sixteen environmental violations, planted over 800 seedlings in our riverbanks, and monitored previously planted areas to replace seedling mortality due to El Niño. They also monitored 66 species of trees and plants, forty (40) species of mammals, five (5) species of birds, and one species of amphibians identified using their local terms since 2019.

While efforts to rehabilitate the Panigan-Tamugan and all other watersheds in the city pose a great challenge, the environmental groups recognize the important role of the Bantay Bukid volunteers in protecting the environment.

“As environment advocates, we need the support from our communities, so that our campaign to protect the environment can be effective. We now see how important the Bantay Bukid’s role is, not just to protect the environment but also to ensure their ancestral land is not being exploited; that this land is their identity and source of their livelihood,” said EGIP Foundation Project Coordinator Joshua L. Donato. (davaotoday.com)