For Good Luck. The offerings on the stairways that the owner of the house in Kampung Ensika especially offers to Mujah for visiting their house on the second day of the gawai. “It means good luck,” Mujah says, for the house owners regard his visit as good omen for things to come in their fight for ancestral land. It was the second day of the gawai when people leave the longhouse to visit surrounding, individual houses to renew ties and friendship. (davaotoday.com photo by Germelina A. Lacorte)

INSIDE the halls of Sarawak�s University of Malaysia (UNIMAS), Prof. Jayl Langub, senior researcher of the Institute of East Asian Studies (IEAS) laughs at the images of scantily clothed Sarawak tribes and their blowpipes depicted on tourist brochures.

�Those are only for show,� he says. �They love to give tourists what they want, so, for a day or two, they dress and act like they still belong to the past. When the tourists are gone, they go back to their own lives.�

What greatly concerns the tribes nowadays is economic survival, rather than the more abstract concerns of culture and religion, says Langub. Land rights issues and livelihood are foremost in their minds.

�Those indigenous peoples (depicted in brochures), you can�t find them anymore because most of them are already in the urban areas,� he says. �One of them is talking to you right now.�

For Langub himself belongs to the Longbawan tribe, one of the smallest tribes in Sarawak, fast assimilating to the mainstream culture. As a Longbawan living in urban Kuching, he expressed what it felt like being sucked into the grind of mainstream urban culture while trying to find ways to keep his culture — the mainspring of his own identity — alive.

�Our way of life has changed,� he confides. �Not that we had a choice. We had very little choice.�

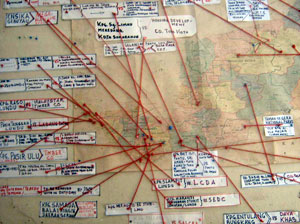

Disputed Lands. Most of the native customary lands in Sarawak where indigenous peoples live are now being taken away by companies. A portion of the map on the wall of Mujah’s office SADIA showing these disputed lands. (davaotoday.com photo by Germelina A. Lacorte)

More people are leaving the farms to migrate to the cities to look for jobs, he says. In doing so, they become participants in the mainstream urban culture, which is drawing them away from the beliefs of their ancestors. �It�s part of the post modernist realities that the tribe has to deal with,� he says.

But for Langub, it�s not so much the dominant religion as the fast-paced demand of urban life that is tearing himself away from his cultural roots. �Religion is not a problem,� says Langub, who, like most of the Longbawan tribe, has converted to the more dominant Roman Catholic religion in Sarawak.

�I still get to practice some of the old rituals even if I�m a Christian.� Both the Anglican and the Catholic faiths are more tolerant of the tribes� beliefs, he says.

But it is the fast-paced demands of urban living that are robbing him of time he could have spent for himself and his own people. While rural life renders time as immaterial, urban life is characterized by a wild scramble for time.

�If you look at the indigenous person living in this city, he has to keep a timetable. When he goes to the market, he probably has a list. He has to take his kids to school because if he doesn�t, his kids will have problem adjusting to life in the area. Added to that, he has to attend staff meetings just to ensure he will go up the ladder. Everything is fixed around these activities that make him a participant in the urban culture and in the end, it�s his culture and his roots that are being neglected,� he says.

Indigenous Peoples