There are two theories that define the state of the Philippine press today � the bourgeois theory and the progressive theory. The bourgeois theory of the press retains its domination of the industry but with a new breed of owners and stockholders belonging to new wealthy families. The author read this paper at a conference of the College Editors Guild of the Philippines (CEGP) in Dumaguete City on April 14.

By Bobby Tuazon

Bulatlat

Any discussion about the theories of the press, to make them relevant to Philippine realities, should always be taken in the context of the social, economic and political conditions in a given historical period. Today, the continuing political crisis, armed conflict and even the state of rebellion are also manifested or mirrored in the state of the Philippine press.

To my mind, there are two theories that define the state of the Philippine press today. One is the bourgeois or corporate theory of the press, which some progressive groups also describe as reactionary. The other is the progressive theory, also referred to as “advocacy” or “alternative” theory. Necessarily, the two theories contradict each other, a situation that reflects the state of Philippine society as a whole.

The bourgeois theory traces its historical roots to the U.S. colonization of the Philippines at the turn of the 20th century. The U.S. colonialist conquest of the Philippines that led to a protracted war resulting in the killing of more than one million Filipinos, was fanned by U.S. newspapers particularly those owned by William Randolph Hearst and the “yellow journalism” or sensationalism of Joseph Pulitzer which circulated black propaganda about Filipino “savages,” alleged brutalities committed against U.S. troops and the need to Christianize and civilize the Filipinos. Ironically, while a group of Americans also began to establish newspapers in the Philippines, the U.S. colonial regime undertook a campaign of censorship and anti-sedition laws that were designed to suppress struggles for an end to colonial rule. In the long U.S. colonial rule of the Philippines, the bourgeois press introduced by the Americans supported colonialist aggression and the corporate interests of U.S. capitalism.

Eventually, in the post-independence period, the pro-imperialist, pro-corporate bourgeois press was continued but even as wealthy Filipinos established newspapers and then, later, radio and television stations, some Americans were still in control of a number of media establishments. Filipino elite families who began to monopolize the media industry considered their ownership of press establishments as a private enterprise � indeed, along the lines of American capitalism � and appropriated for themselves the civil libertarian doctrine of “freedom of the press” and “freedom of expression.” In fact, however, the elite ownership of major newspapers, radio and TV networks basically had nothing to do with press freedom. What they were after was to use media ownership to promote their corporate interests as well as the vested interests of politicians or the political elite.

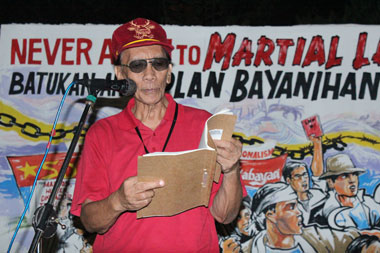

The Marcos dictatorship (1972-1986) led to the monopolization of the media industry by the Marcos families and their cronies. Under Marcos, the bourgeois press assumed an authoritative streak supported no less by martial law censorship. Many progressive journalists were arrested and held in military stockades, anti-Marcos newspapers and broadcast stations were closed or taken over by Marcos cronies. Newspapers, radio and TV networks run by Marcos cronies served as mouthpieces of the dictatorship under supervision of the Department (later, Ministry) of Public Information. The Marcos regime established the Kapisanan ng mga Brodkaster ng Pilipinas (KBP or Association of Broadcasters of the Philippines) as a means of controlling the broadcast industry under the doctrine of self-censorship.

Today, more than 20 years after the fall of the Marcos dictatorship, the bourgeois theory of the press retains its domination of the industry albeit with a new breed of owners and stockholders belonging to new wealthy families, many of whom come from the Filipino-Chinese elite. The bourgeois press, however, has a new dimension in the sense that major media owners have extensive interlocking interests such as chains of malls, hotels, real estate, food and beverages, construction, banking, and so on. Globalization has transformed the media industry into conduits or appendages of the so-called global media village of cable TV networks, cyberspace, Hollywood movie industry, giant advertising corporations, and sometimes even schools of mass communication. The bourgeois press promotes a culture of consumerism and commercialism, generally toe the government line, and shun investigative journalism or publicize issues of public concern. Consumerism has given rise to the tabloidization or sensationalism of the press including the TV news and public affairs.

The bourgeois theory of the press claims to represent balanced news, objectivity and neutrality. However, what it practices is the reverse of what it preaches. For instance, the press in the United States, from where the bourgeois or liberal theory of the press originates, is monopolized by financial oligarchs and mergers of the likes of CNN, Fox and other monopolies that are not necessarily the embodiment of fair and true reporting. The liberal press in the U.S. features elements of authoritarianism and censorship. The media monopolies promote not only decadent consumerism and obesity in the American society but also support wars of aggression, the trading of weapons of mass destruction and economic globalization that has only resulted in the destruction of Third World economies as well as in global unemployment, poverty and massive outmigration of skills.

It is even worse in the Philippines. Owners of media corporations pay lip service to freedom of the press and balanced news when in fact what the Filipino media consumer receives are stories slanted in favor of government or stories that glorify consumerism, of mediocre actors and showbiz personalities so that people will patronize their products and services. There is hardly any news about agrarian reform, human rights, urban poor, the indigenous peoples, the threats of campus militarization or suppression of the campus press, or about the social, economic and political roots of the armed conflict. In other words, the bourgeois press does not mirror the harsh realities of Philippine society.

Right within their own media enterprises, owners and publishers violate the rights of their own employees by preventing the formation of unions and imposing self-censorship among their rank-and-file journalists. How many of them have lent any support to the families of over a hundred of journalists who have been killed since the Marcos years � 50 of them under Arroyo alone � by suspected police officers, hired goons and corrupt politicians? How many of them have protested against the enactment of the Human Security Act of 2007 which essentially violates the people’s bill of rights and civil liberties, including the freedom of the press and free expression?