Imee Marcos, senator and also creative producer of the film Maid in Malacañang, said something about this movie as art that is meant to disturb, provoke, and stir discussions. Well, it did provoke me to laugh at a crucial scene that disturbed the audience.

That scene was near the end part, after the Marcoses had said their goodbyes to their crying servants and staff as they made their escape from Malacañang. After that scene, Imee ordered those servants and staff to shred her mother’s yellow gown to make up yellow headbands so that they can blend with the incoming mob and escape. That scene may have tried to show ingenuity or desperation, but the way it was executed, with slow-motion scenes of servants wailing for stripping off a beautiful dress and tying those strips (or Retaso, as that scene chapter was titled), just drew out laughter for its hilarity.

I may be jumping ahead of my review, or I may be showing my bias. But then a review is always a criticism, whether a film is good or bad art. In this case, whether this so-called historical film is indeed historical (or hysterical) or, even for the sake of creative recreations of history, does it reveal why things happened and how characters in history evolved?

For that, Maid in Malacañang, is a jumble of melodrama and comedy. But there is never a sense of suspense or tension, as what this film claims to show the real story of the last days of the Marcoses in Malacañang.

What we were shown in the film is a typical Filipino drama, family screaming at each other, then tears, and then a resolution. Most of the screaming is made by Imee, played here by Christine Reyes, who screams at guards and staff, at her siblings, at her mother reluctant to leave by screaming “pinapaligiran tayo ng mga ahas!” (I wonder if this is really how she feels at politicians who have abandoned them in 1986 and crawled back to them again).

There’s also a bit of screaming between Ferdinand and Bongbong, which was also seen in the trailer, the strongman father berating his junior who knows nothing about the nation’s affairs for he spends more time in clubs and parties. It was fun to see Cesar Montano showing his acting chops here with his real son Diego, who tears up saying he may not have the brains but has the heart, and they give each other a hug.

The comedy part is provided by the three maids – the headmistress Lucy (Elizabeth Oropesa), Santa (Karla Estrada) with her Imelda-inspired hairdo, and the loquacious Biday (Beverly Salviejo). In typical fashion of Filipino cinema, maids are there to provide comic relief, as when they make sumbong of a military aide who joined the rebellion, or of Cory playing mahjong during EDSA. There’s also that scene where Santa commands the whole Malacañang staff on their escape plan like a platoon leader with put-downs and insults. The three actresses by the way are Marcos supporters.

But where is the history part as the film suggests? Even if the film inserts historical news footages of Juan Ponce Enrile and the late Fidel Ramos defecting from government, there’s nothing about the snap elections, or the walkout of Comelec tabulators due to manipulated results.

What the film shows is just a family in a crisis moment and how they bond together. It is about a family portrayed as benevolent hacienderos who are caring for their staff, and believe that they are being booted out by ahas because they are probinsyanos (that comes from a line from Cesar).

There is much melodrama in the family in the Palace as the country rages outside, like scenes in All of Us Are Dead, where characters comfort each other.

But according to the book Ferdinand Marcos: Malacañang to Makiki written by Colonel Arturo Aruiza, a military aide to the Marcoses, the last days in Malacañang were filled with chaos. Bags of clothes, boxes of jewelry, and money, were all hurriedly brought down from the stairs. Documents being burned that Imee had it stopped as the smoke was triggering her asthma. The film showed nothing like that. Military generals plotting with Marcos on how to stop EDSA were invisible (except for a news footage).

Historian Chris Bouton says history can be viewed by books, museums, archives, and also in films. Good historical films for him explore the context of their characters and times, bad historical films “fail to meaningfully engage with their subject matter. Favoring gruesome effects or conventional tropes over exploring the nuances of their subjects.”

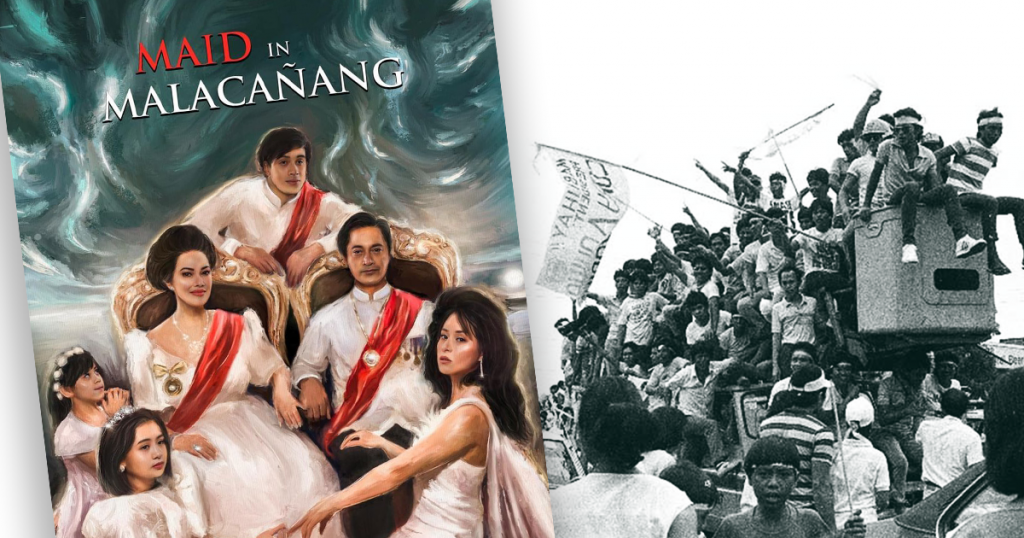

There are so many “conventional tropes” in this movie. But what is worse is the film distorts facts and denies facts. It did not explain totally why People Power happened. It depicts Filipino protesters barging into Malacañang as torch-wielding angry zombies. It depicts Cory Aquino as a mahjongera who ordered the Marcoses to fly out.

Is this alternate history? No. It is melodrama. It’s the Marcoses using cinema to re-create themselves as a family wronged by history. The problem with that is how the audience will take this, given that we have been fed with that soap-opera theme for decades of rich families being wronged. The Marcoses portray themselves as that family. The Marcoses know cinema, their late father made a biopic to help his presidency, the daughter, who is called “darling genius of a girl” in the film, knows what cinema can do.

They portrayed themselves as victims of history. They erase from the audience’s memory the real victims of the Martial Law the late dictator imposed: 70,000 people imprisoned, the 34,000 tortured, and 3,240 killed from 1972 to 1981 as reported by Amnesty International.

Wait, the film is about the yayas, they are in the title. The film’s ending showed the three real yayas as if to depict them as martyrs. Two of them had passed away, drawing gasps and awws. The audience clapped at the end of the film. Were they clapping for the yayas? The yayas who we in our culture are ever loyal and extended family? But the yayas in the film are just props here to provoke that sentimentality. The real star is the M in Malacañang.

I may have laughed at this movie, but I am crying at this state of our nation and the state of such Pinoy films that lull us to dullness, distortions, and divisions in our dark times.

READ: Katips as eye-opener

JD Flores was a frustrated artist who now watches films after work.