DAVAO CITY, Philippines – As August 30 is marked as the International Day of the Victims Enforced Disappearance, the family of missing labor organizer William Lariosa continues to search for him.

The 63-year-old organizer of Kilusang Mayo Uno (KMU) from Davao de Oro was last seen on April 10, 2024, in a farming community in Barangay Butong, Quezon municipality in Bukidnon, where he was taken during an operation of the 48th Infantry Battalion of the Philippine Army.

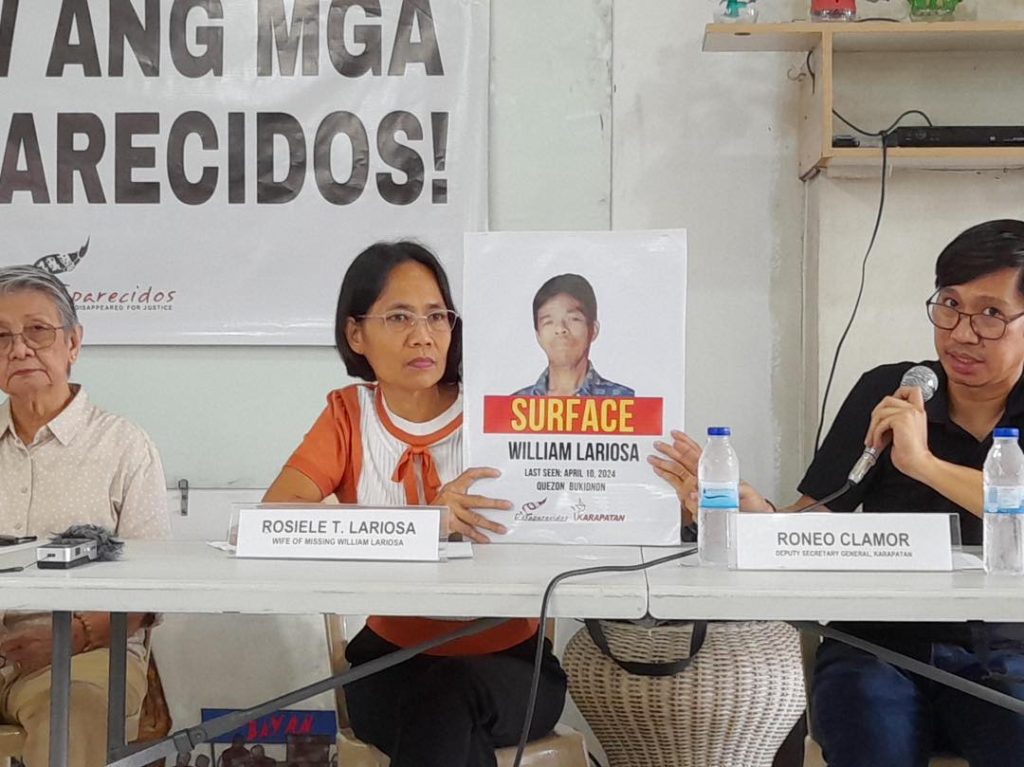

Since his disappearance, his wife Rosiele and their two sons searched for him in military camps from Bukidnon to Davao. They filed petitions in courts that would have compelled the 48th IB to surface him but these were rejected.

“Nag-expect gyud unta mi nga ang korte isip usa ka dangpanan unta sa mga ingon ani nga mga kaso (We were expecting the court as it should be our resort to help in this kind of case),” said Dodong, the son of William.

Theirs is a story of a family wanting justice for their loved one who fell victim to the government’s red-tagging campaign.

Who is William Lariosa?

Lariosa first worked for the NGO Center for Community Health Services in Tagum City before joining KMU in 1996.

Lariosa was later put under military surveillance in 2006, a time that saw union organizers and members in the Davao Region being subject to harassment and attacks.

“If you are pushing for the interest of the workers, you will be red-tagged, be a target for abduction or killing,” William’s other son Marklen said in an interview with Pinoy Weekly.

In their story, the Lariosa family first knew of the red-tagging in June 2022. Four people arrived at their home, one of them identified himself as a former New People’s Army (NPA) member, then alleged William was their comrade whom they wanted to arrest.

Rosiele denied the claim, saying William doesn’t even carry a gun for his work.

They were again approached by military agents from October to November 2023, who coerced them to convince William to surrender or else they will be harmed.

Lariosa has not returned home since the first incident. He sought sanctuary in other places, the last being in the farming community in Butong where he also organized sugar-cane workers.

What happened on April 10

On April 10, Marklen received a call from his father’s phone. It was another person’s voice on the other end, who informed him that his father was taken by the military.

Rosiele went to Quezon the next day with paralegals to find William. They could not visit Brgy. Butong as it was heavily guarded by the military so they went to the barangay officials.

They pointed them to a funeral home where a body of an alleged NPA member was brought there by the military. The body was not Lariosa’s.

They went to the Quezon Municipal Police Station and noticed a truck assigned to the 48th IB parked there. Police said soldiers brought people they arrested but took them to their camp for questioning. They scoured through mugshots of the arrested persons but there was no photo of Lariosa.

They proceeded to the 48th IB headquarters but were made to wait for three hours without anyone engaging them in their inquiry.

Witnesses’ story

Farmers in Butong told Rosiele that Lariosa was staying in one of the houses when the military arrived in their community around eight in the morning. At that time, an encounter was happening between the military and the NPA in a nearby community.

There were five trucks carrying around a hundred soldiers belonging to the 48th IBPA, 1003rd Infantry Brigade, the Quezon Municipal Police (QMP), and bonnet-wearing personnel who rounded up the residents and then went to search the village and nearby communities.

They later heard gunshots as soldiers claimed they had killed a female NPA member and captured three of her companions.

A witness said the bonnet-wearing people found Lariosa from one of the houses and dragged him away. They threw a jacket on Lariosa’s head as one of them collared him and said, “dugay ka na namo gipangita (We have been looking for you for a long time).” The man also drew his gun on the witness to intimidate him.

Lariosa was forced not into one of the military trucks, but rather into a white Toyota Innova with no license plate.

Denials and rejections

Rosiele and paralegals went to various military camps in the past few months: the 48th IBPA in Maramag, Bukidnon; the 1003rd IB in Malagos, Davao City; and the Eastern Mindanao Command sa Panacan, Davao City. All of them denied any knowledge of Lariosa’s whereabouts. All of them also refused to sign documents such as the desaparecido form to acknowledge that the missing person is not under their custody.

A week into Lariosa’s disappearance, the family a writ of habeas corpus in the Malaybalay court which was rejected. The judge said Rosiel’s evidence was based “not on facts or information based on her knowledge but instead, information allegedly supplied by the people in Purok 16, in Bgry Butong.”

Even their petition to the Court of Appeals along with their petition for a writ of amparo and habeas data which seeks a protection order from military harassment, were all rejected.

The CA said the petition did not establish a clear link between the bonnet-wearing men who took William with the battalion. It also noted that battalion officers had “extended efforts looking for William… mobilized their respective commands to assist Rosiele in finding her husband.”

“Murag dili man pud kaayo believable nga nangita sila kay wala man gani mi nila gientertain sa dihang niadto mi sa kampo, (It is not believable that they search for him when they did not entertain us when we went to their camp)” Rosiele told Davao Today.

“Masama ‘yong loob naming. Pinagmukha pang kami ‘yong may kakulangan, (We feel disappointed. They seem to be telling us we lack evidence)” added Marklen.

They continue to seek justice for William. Last August 30, Rosiele joined other families of victims of disappeared activists in a protest action at the University of the Philippines Diliman.

KMU also marked every 10th day of the month with protest activities and has raised Lariosa’s disappearance to the International Labour Organization last August among the labor rights issues happening in the nation.

The human rights group Karapatan said that with the denial of legal remedies, the families have to look for remedies in the international community through the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (WGEID) under the United Nations Human Rights Special Procedures.

The families raised a collective call that such incidents need to stop.

“One desaparecido is already too much. Let us not further allow the Marcos Jr. government to rob us of our loved ones, rights and justice,” the group Desaparecidos said in their statement. (davaotoday.com)

davao region, desaparacidos, desaparecidos, Red-tagging, William Lariosa