Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte. (Photo by Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines)

by Karol Ilagan and Malou Mangahas

THE IMAGE Rodrigo R. Duterte projected of his 2016 presidential campaign was that it was one run on a shoestring budget. It supposedly had no donors with vested interests, and that included big businessmen and mining firms.

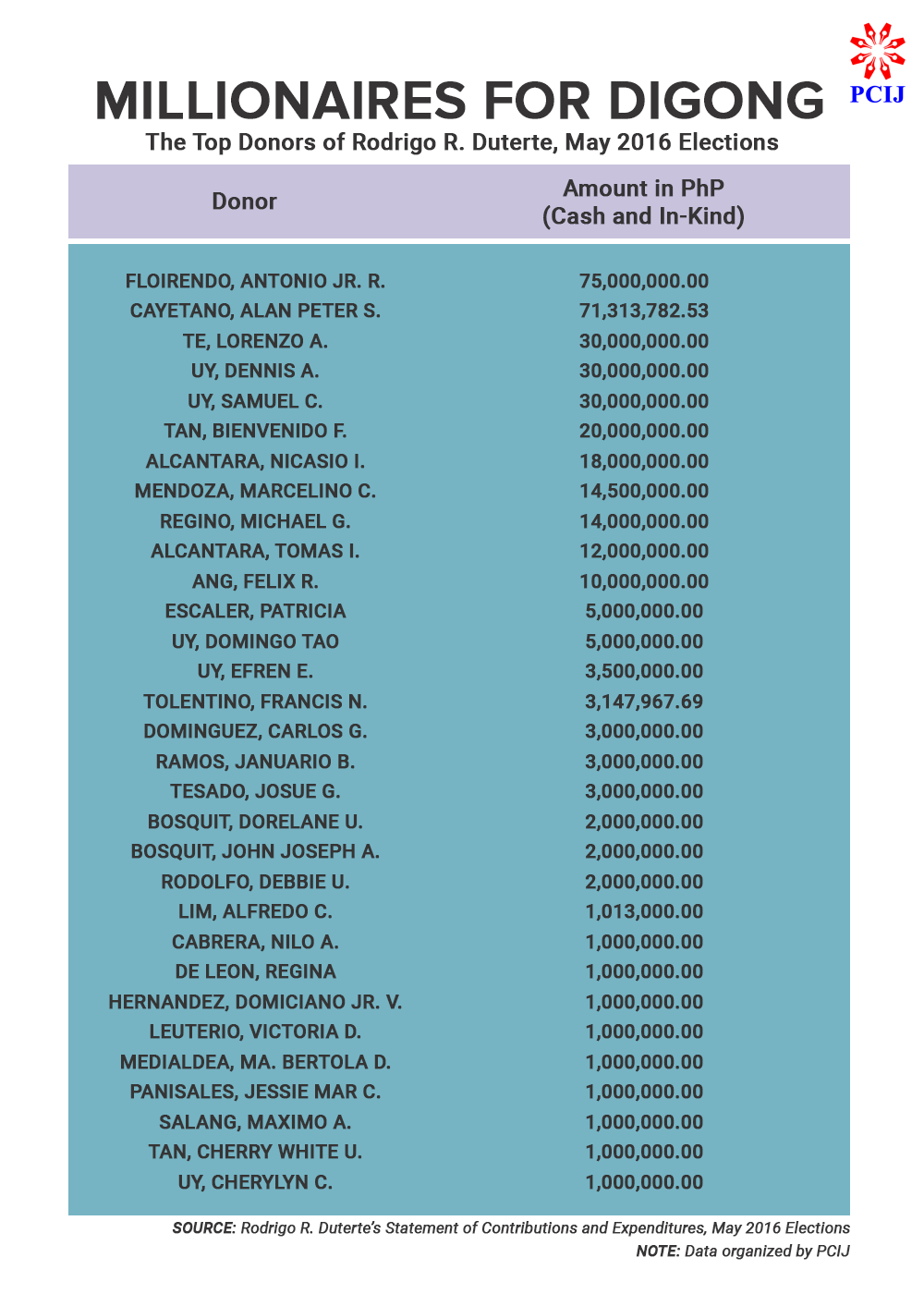

But the Statement of Contributions and Expenditures (SOCE) he filed with the Commission on Elections (Comelec) after he won the presidency paints a different picture. According to his SOCE, the P375 million Duterte raised for his campaign came mainly from big businessmen.

In fact, money from his 13 biggest donors who gave him P5 million or more already makes up 89.28 percent or P334.8 million of his total campaign kitty. One of these contributors even belongs in this year’s Forbes list of 50 richest Filipinos. Small donations or those P10,000 and below amount to just P175,313 — less than half of one percent or merely 0.046 percent of Duterte’s total campaign fund.

A second tier of 18 other donors who donated from P1 million to P3.5 million delivered an additional P31.66 million, or eight percent more, to Duterte’s campaign.

No doubt, this is far from how Duterte and his followers had described his campaign team: That the masses who could afford to donate only “Emilio Aguinaldo” money or five-peso coins would be the ones sending him to Malacañang.

By the data he enrolled in his SOCE, only 13 extremely wealthy individuals and 18 other million-peso donors whose companies do business with the government or engage in utilities, mining, and the exploitation of natural resources bankrolled Duterte’s rise to power.

Just six months after the elections, Duterte has appointed at least half a dozen of his donors and their relatives to Cabinet and other positions, even as one campaign contributor has already snared government contracts and flaunted on social media his claimed closeness to the President.

BY THE PRESIDENT’S SEAL. Duterte donor Samuel ‘Sammy’ Uy stands against the seal of the President of the Philippines, hands nimbly settled on the podium. Photo from Sammy Uy Facebook page.

This donor, a Chinese-Filipino business partner of Duterte who runs a cockpit in Davao City, has even posted on his Facebook page his photos with the President and the Japanese premier that were taken from Duterte’s recent state visit, as well as with Duterte, and his children and sibling.

And yet by the rules of the Commission on Elections (Comelec), this campaign contributor and several others should not have donated at all to Duterte’s campaign. Section 95 of the Omnibus Election Code prohibits “natural and juridical persons” who have business interests in utilities, mining, and the like from making election contributions.

CFO headless, in drift

PCIJ curated, digitized, and reviewed Duterte’s SOCE, as well as those that the other candidates for president, vice president, and senator in the May 2016 elections have filed with Comelec. Altogether, these documents, including advertising contracts, broadcast logs, and various SOCE forms, came up to about 12 gigabytes of data. PCIJ also secured records from the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) for some of the companies of some of the campaign contributors, and sent letter requests to the candidates and their donors for comment and clarification.

The PCIJ audit reveals that Duterte and some other candidates may have some explaining to do with Comelec for their failure to disclose the true identities of their donors, for overspending, for failure to file complete and correct SOCEs, or even for not filing their SOCEs within deadline of one month after the May 9, 2016 elections.

When or how the poll body will act on these matters is the big question, though. Last June 20, Commissioner Christian Robert S. Lim, filed his irrevocable resignation as head of the Comelec Campaign Finance Office (CFO). This was after four of the poll body’s seven commissioners voted to accept the late submission of SOCEs by the Liberal Party and its presidential candidate Manuel ‘Mar’ Roxas II until June 30, or three weeks beyond the “final, non-extendible deadline” deadline it had imposed.

In his resignation letter, Lim wrote the Comelec en banc: “Given the Commission’s policy shift resulting from granting the request for extension without any sanctions on the erring candidates and parties—which I had expressly dissented from and is now incongruent with my own views on the matter—I believe that I am unsuitable to continue with my duties both as the concurrent head and Commissioner-in-Charge of the Campaign Finance Office.” According to Lim, the extension of the deadline for the Liberal Party was “illegal… tantamount to an amendment of the law.”

Court case drags

In July, Duterte’s political party, the Partido Demokratiko Pilipino-Lakas ng Bayan or PDP-Laban asked the Supreme Court to declare the Comelec’s decision “illegal, prohibited, and void,” saying the deadline extension was made to “accommodate” the then ruling Liberal Party.

The Supreme Court has yet to rule on the matter. A court official told PCIJ that the justices are not likely to deliberate and rule on the case soon, on account of other pending contentious cases and the usual holiday downtime.

Should the court rule against Comelec, at least 69 winning candidates and 5,836 losing candidates for national and local positions in the May 2016 elections could face penalties or sanctions under Comelec’s campaign-finance rules. If it should rule for Comelec, however, the court is likely to court the disfavor of the PDP-Laban party of President Duterte.

But by all indications, whichever way the high court decides — for or against Comelec — the issue has already left the CFO in limbo and adrift, and set back the reforms in campaign-finance regulation that Comelec has been putting in place since the 2010 elections.

More than five months after Lim’s resignation, the CFO remains a headless entity. Indeed, the CFO lawyers have had to seek endorsement from the office of the Comelec’s Executive Director before they could act on PCIJ’s requests for data and interview. Amid this drift, the staff personnel have been left to mind the CFO household even as they have neither mandate nor power to decide on issues, such as what the Comelec en banc alone possesses.

Among PCIJ’s queries pertained to Duterte’s campaign-finance report, which indicated a bevy of donors who shouldn’t have been making campaign contributions in the first place, and ties binding politics and business.

Still, Mazna Lutchavez, Attorney IV at the Comelec CFO, is firm in saying that a careful reading of the poll body’s rules suggests that Duterte’s donors are covered by the prohibition on giving donations, if they are engaged in mining, public utilities, and government contracts.

This is because, she says, the law specifically cites not only juridical persons or companies, but natural persons, too. She adds that the provision citing direct and indirect involvement also pertains to the company owner.

Then again, Lutchavez allows that the legal doctrine that separates a person from a company offers a loophole that may subject the election rule to different interpretations. For instance, says another election lawyer, a campaign donor engaged in mining, could say as a defense that he owns a mining firm but it is his company that engaged in a mining activity – not him.

The ties that bind

To verify the business interests of Duterte’s donors, PCIJ cross-checked details of his SOCE against corporate records obtained from the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), bid notice and award data from the Procurement Service-Philippine Government Electronic Procurement System (PS-PhilGEPS), public-works contracts from the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH), mining-tenements data from the Mines and Geosciences Bureau (MGB), and PCIJ’s list of campaign donors culled from Comelec records from the 1998 to 2013 elections.

A person’s tax identification number and a company’s registration number were used to match records from different sources.

PCIJ also sent a letter to Duterte through his Executive Secretary Salvador Medialdea on Oct. 22, 2016. The President has yet to respond to PCIJ’s questions as of this writing, although lawyer Ryan Acosta of the Office of the Executive Secretary says that PCIJ’s letter has been forwarded to the Office of the Special Assistant to the President, Christopher Lawrence ‘Bong’ Go. A reply email came mid-afternoon of Dec. 3 with comments from unnamed “Duterte campaign team lawyers” but these have reportedly not yet been cleared with or approved by the President.

Donors from Davao

Among Duterte’s biggest donors are those whose companies do business with the government. These include Duterte’s top donor, Davao del Norte Rep. Antonio ‘Tony Boy’ R. Floirendo Jr., who contributed P75 million in cash to Duterte and another P25 million to the President’s party, PDP-Laban.

Floirendo’s late father was the founder of Anflo Management and Investment Corporation (Anflocor), which oversees at least 11 businesses engaged in agriculture, trading, realty, hotel and restaurant services, financing, and others. Today Tony Boy Floirendo is one of Anflocor’s major stockholders.

Anflocor’s flagship company is Tagum Agricultural Development Company Inc. (TADECO), one of the highest-yielding banana plantations in the world. TADECO has a long-term joint venture agreement with the Bureau of Corrections, in which inmates of the Davao Penal Colony work at its banana plantations. The joint venture agreement between TADECO and BuCor was renewed for another 25 years in 2004.

Tony Boy Floirendo is chairman and stockholder of TADECO, according to the company’s latest available document at the SEC, its 2013 general information sheet (GIS). He is married to 1973 Miss Universe Margarita Moran, granddaughter of Manuel A. Roxas, the country’s fifth president.

BETWEEN TWO LEADERS. Duterte’s top donor Samuel ‘Sammy’ Uy is flanked by the President and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Photo from Sammy Uy Facebook page.

Another Davao City business bigwig who donated to Duterte’s presidential campaign – P30 million, in fact — is Samuel C. Uy.

From the looks of it, however, Uy has not remained in Davao only after the elections. Uy’s Facebook account photos show him posing with Duterte and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe at the Philippine President’s recent state visit to Tokyo, as well as with the President’s children, and with Special Assistant to the President Bong Go. One photo even shows Uy standing in front of the seal of the President of the Philippines, his hands resting comfortably on the presidential podium.

Uy is a stockholder in several companies, including DIMDI Centre Inc. and DIMDI Builders Center Inc., two government suppliers.

From January 2013 to October 2016, DIMDI Centre and DIMDI Builders Center had been awarded with government contracts worth a total of P2.7 million, PhilGEPS data show. Both companies are also on PhilGEPS’ list of registered suppliers as of Oct. 7, 2016.

DIMDI Centre and DIMDI Builders are both engaged in merchandising. They have supplied photocopying machines, air-conditioning units, television sets, and other appliances to various government offices in Davao. Among these are the regional offices of the Department of Agrarian Reform, Technical Education and Skills Development Authority, Department of Science and Technology, Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corporation, and the City of Davao.

In 2015 and 2016, the City of Davao awarded DIMDI Centre with at least five contracts worth a total of P333,730, PhilGEPS data show. Duterte was Davao City mayor at the time.

Uy’s other business interests include the New Davao Matina Gallera, the “biggest cockpit arena in Davao City” located on MacArthur Highway in Matina district. It features, among others, arena-style seating, wide-screen scoreboards, air-conditioned cockhouse and cockpit, and livestream and satellite feed of the derbies. The cockpit’s derbies have drawn avid following among governors, mayors, and military and police officers.

In business with DU30

Uy and President Duterte, along with Lorenzo A. Te Jr., Azucena Angbue, Jan S. Ced, Eugenio O. Ced, Divino M. Tan II, Danilo D. Tan, and Jesus Y. Tan, are also stockholders of Honda Cars General Santos Inc.

Uy, Duterte, and Te are incorporators as well of Poeng Yue Foundation, along with James S. Gaisano, Josue G. Tesado Sr., Johnny Lee Ng, and Samuel G. Afdal.

Like Uy, Davao City businessman Te had given P30 million to Duterte’s campaign.

“Friend” in Mandarin, Poeng Yue was formed by Duterte and his business partners in 2012 to “extend assistance, financial or otherwise, to cancer patients with special focus on children suffering from said disease.”

Honda Cars General Santos City and Poeng Yue Foundation are two business interests Duterte has declared in his Statements of Assets, Liabilities, and Net Worth (SALN). His SALN upon assuming the presidency or as of June 30, 2016 shows that he did not divest from these two entities.

Civil Service Commission Assistant Commissioner Ariel G. Ronquillo says the need to divest may not necessarily be automatic. First, he says, one has to determine whether or not there is a clear conflict as President of the Philippines and as incorporator of a company. According to Ronquillo, a conflict of interest may occur if a business is getting a permit or license from one’s office. “Naturally,” he says, “there is a conflict because you’re the one giving the license so you should not have any interest there.”

Government contractors

But what about campaign donors who have companies that have business with government? Aside from contributions from Davao-based businessmen, the Duterte campaign had also accepted donations from those like Felix R. Ang, whose company later landed a deal with a state agency.

Ang donated P10 million to the Duterte campaign. He is an incorporator, stockholder, and chairman of Cats Asian Cars, which bagged a P1.24-million contract with the Social Security System for the supply and delivery of one brand new sedan in October 2016.

Yet another Duterte campaign contributor, Marcelino C. Mendoza, is president and stockholder of MGS Construction, which appears in PhilGEPS list of registered suppliers.

Mendoza, who donated P14.5 million to help finance Duterte’s presidential bid, is from Las Piñas. He is listed as well as incorporator, board member, and stockholder of Vista Land & Lifescapes, Inc. Vista Land’s chairman is former senator Manuel B. Villar Jr. Its president and chief executive officer is Villar’s eldest child, Manuel Paolo. A week after he won the presidency, Duterte appointed Paolo’s brother Mark as Public Works and Highways Secretary.

Januario B. Ramos, meanwhile, donated P3 million to the Duterte campaign. Ramos is president, incorporator and stockholder of Pragmatic Development and Construction Corp., a registered contractor with the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH).

Pragmatic’s website says the firm, formed in 1979, specializes in “roads, highways, pavement and bridges irrigation, and similar industrial projects,” but has recently branched out into real-estate development and property management.

According to DPWH’s online registry of awarded contracts, Pragmatic has won at least three contracts altogether worth P64.75 million from the DPWH Cebu City Engineering District Office from 2014 to the present. One was worth P38.06 million, for the widening of the Canduman-Cebu North Road from May 4, 2015 to March 11, 2016; another was valued at P18.33 million, for the widening of the Canduman North Road-Mandaue City from Feb. 5, 2014 to Oct. 18, 2016; and a third, P8.36 million, for the concreting of J. Luna Avenue-Cardinal Rosales Intersection from March 3, 2015 to March 3, 2017.

From 2001 to 2014, Pragmatic was also awarded P48.1 million worth of government contracts, almost all located in Cebu, according to PhilGEPS and DPWH databases.

The firm had also donated P280,000 in cash to the Bagumbayan-VNP party in the 2013 elections, according to PCIJ’s SOCE database.

Mining concerns

Persons affiliated with firms that operate public utilities or those that possess or exploit the country’s natural resources are also among Duterte’s 10 biggest donors. These include Michael G. Regino, who contributed P14 million to Duterte’s campaign. SEC records filed in 2016 show that he is director and minor stockholder of TVI Resource Development Philippines Inc.

Interestingly, TVI Resource’s vice chairman is Manuel Paolo A. Villar. TVI Resource is the Philippine affiliate of TVI Pacific Inc., a publicly-listed Canadian mining firm that is exploring, developing, and producing precious and base metals in the Philippines.

Mines and Geosciences Bureau data as of July 2016 show that TVI Resource holds a mineral production sharing agreement (MPSA) with the government and is applying for another MPSA and exploration permits in the Zamboanga Peninsula region.

According to TVI Resource’s website, Regino sits on the board and maintains top positions in other companies led by Prime Asset Ventures Inc. He is president of St. Augustine Services Inc., senior vice president of St. Augustine Mining Ltd., and board member of Nationwide Development Corp. and Kingking Mining Corp. In addition, Regino is president and minor stockholder of Agata Mining Ventures Inc. and Equipment Drilling Corp., which are both subsidiaries of TVI Resource.

Public utility

Then there are brothers Tomas and Nicasio I. Alcantara, who contributed a total of P30 million. Tomas and Nicasio are stockholders of Alsons Development and Investment Corporation and several other businesses.

Tomas is chairman and president of the Alsons Power Group, which is composed of power generation facilities across Mindanao. According to its website, Alsons Power Group operates three diesel-power facilities, one each in Alabel in Sarangani, Zamboanga City, and Iligan City. In April 2016, the group’s first coal-fired power plant located in Maasim, Sarangani started commercial operations.

Tomas is No. 41 on the 2016 Forbes list of the 50 richest Filipinos. The Alcantara family had also been included in previous Forbes lists of richest Filipinos.

Tomas and Nicasio Alcantara are stockholders as well in Alsons Consolidated Resources Inc., as is another Duterte campaign donor, Carlos G. Dominguez.

Dominguez, who donated P3 million, is also linked to yet another top Duterte donor, Bienvenido Tan, through PTFC Redevelopment Corporation, a real estate company. Tan, who gave P20 million to Duterte, is president and stockholder of PTFC. Dominguez and his management firm CG Dominguez Associates Inc. are also stockholders of PTFC Redevelopment Corporation.

Donors & appointees

Dominguez is now Finance Secretary in the Duterte administration. Aside from him, other Duterte campaign donors have wound up in government themselves.

For instance, Dennis A. Uy of Davao City was named presidential adviser for sports last July. The president and chief executive officer of Phoenix Petroleum, Uy and his wife Cherylyn gave a total of P31 million in cash to the Duterte campaign. Cherylyn also gave P5 million to PDP-Laban.

Similarly, Salvador Medialdea and wife Ma. Bertola donated a total of P1.5 million to Duterte. Medialdea is now Executive Secretary.

Ismael Sueno donated P21,600 in kind for “sound system rental and flat cord.” He was appointed secretary of the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG).

Bacolod-based lawyer Jesus V. Hinlo Jr. was also appointed by Duterte as DILG undersecretary. Hinlo donated a tarpaulin worth P576 to Duterte. This is one of two P576 donations the president received and also the lowest.

Hinlo was reported to be focusing on the DILG’s Bureau of Jail Management and Penology, Bureau of Fire Protection, national emergency hotlines 117 and 911, and the Public Safety College.

Legal but not right?

“It’s not legally prohibited,” lawyer Rona Ann V. Caritos, executive director of the Legal Network for Truthful Elections (LENTE), says of the appointment of campaign donors to government posts. “But all these things that are not prohibited in law do not necessarily mean that they are right.”

Section 4 titled “Norms of Conduct of Public Officials and Employees” of Republic Act No. 6713 does say that every public official and employee shall observe professionalism, among others. This means they “shall endeavor to discourage wrong perceptions of their roles as dispensers or peddlers of undue patronage.”

But CSC’s Ronquillo — who also heads the Commission’s Office for Legal Affairs — says the President, being the appointing authority of his people, enjoys the widest latitude of discretion to appoint whoever he wants to positions. The appointments are actually subject to the President’s trust and confidence, he says. These people are confidential appointees — co-terminus with the chief executive — so it’s only natural for the president to choose people whom he trusts, Ronquillo says.

“Hindi ka naman mag-aappoint sa position na hindi mo kakilala (You will not appoint people you do not know),” he says. “You will appoint those you’re comfortable with because these are the people who will help you deliver the promises that you made during the campaign — to deliver the services that you want to deliver to the people.”

‘Utang na loob’

Ronquillo says that Duterte was not in violation of the law when he appointed his donors. The law, he says, will now apply to those the President appointed. In the course of discharging their functions, says Ronquillo, appointees cannot favor only members of their party or a certain group of people who happens to be close to them or to the president.

“When you’re in public office, your boss is the Filipino people so you shouldn’t be favoring anyone,” he says. “Doon papasok ngayon na ‘they shall endeavor to discourage wrong perceptions of their roles as dispensers or peddlers of undue patronage.’”

Caritos, however, frets that when it comes to appointments, those who contributed to the victor’s campaign tend to be given priority over others. This is why, she says, LENTE always highlights in their voter education activities that people should know who the donors are. It’s human nature, Caritos says; especially among Filipinos where the concept of utang na loob endures, it’s not unusual to expect someone to give something in return to a person who gave him something.

And yet there are the likes of Senator Alan Peter S. Cayetano and former Metropolitan Manila Development Authority Chairman Francis N. Tolentino, both of whom donated substantial amounts to Duterte but hold no appointed position at present. Cayetano’s and Tolentino’s donations were in the form of tandem advertisements worth P71.3 million and P3.15 million, respectively. Cayetano was Duterte’s running mate; he has since become a perennial presence in events attended by the President, including those abroad. He was said to be eyeing the top post at the Department of Justice, but this went to Duterte’s former law school classmate Vitaliano Aguirre II.

Caritos has a different bone to pick with Cayetano and Tolentino, however. She says that while no law is violated by elected and former officials donating to campaigns, there is a need to highlight the fact that they hold or held positions in which salaries would not go over half a million pesos per month.

Asks Caritos: “How can these individuals give those inordinate amounts to their fellow party members? Kahit hindi bawal, saan galing ang pera mo para makapag-donate ng ganyan (Even if it’s not breaking any law, where did you get the money to be able to donate that much)?”

— With research by Floreen Simon, Fern Felix, Vino Lucero, Davinci Maru, Ana Isabel Manalang, Steffi Sanchez, Jil Caro, and John Gabriel Agcaoili, PCIJ, December 2016