Davao is indeed turning into a “center of attraction” with a mayor-president steering the “national ship” as many scholars would describe it as a stark departure from its peripheral past. Davao is becoming way busier along with heavy traffic and huge construction projects. With President Duterte’s active pivot to Asia’s giants such as China and Japan and, as he claims, an “independent” foreign policy away from the Philippines’ longtime ally the USA, the question remains: is this an unprecedented situation? Definitely not. Historically, the linkages of these four nation-states and their nationals existed since the prewar era. Now with the recent visit of Duterte in Japan, it cannot be helped to also think about its immediate past – the classic case: interwar years that is the period after the First World War prior to the Second World War

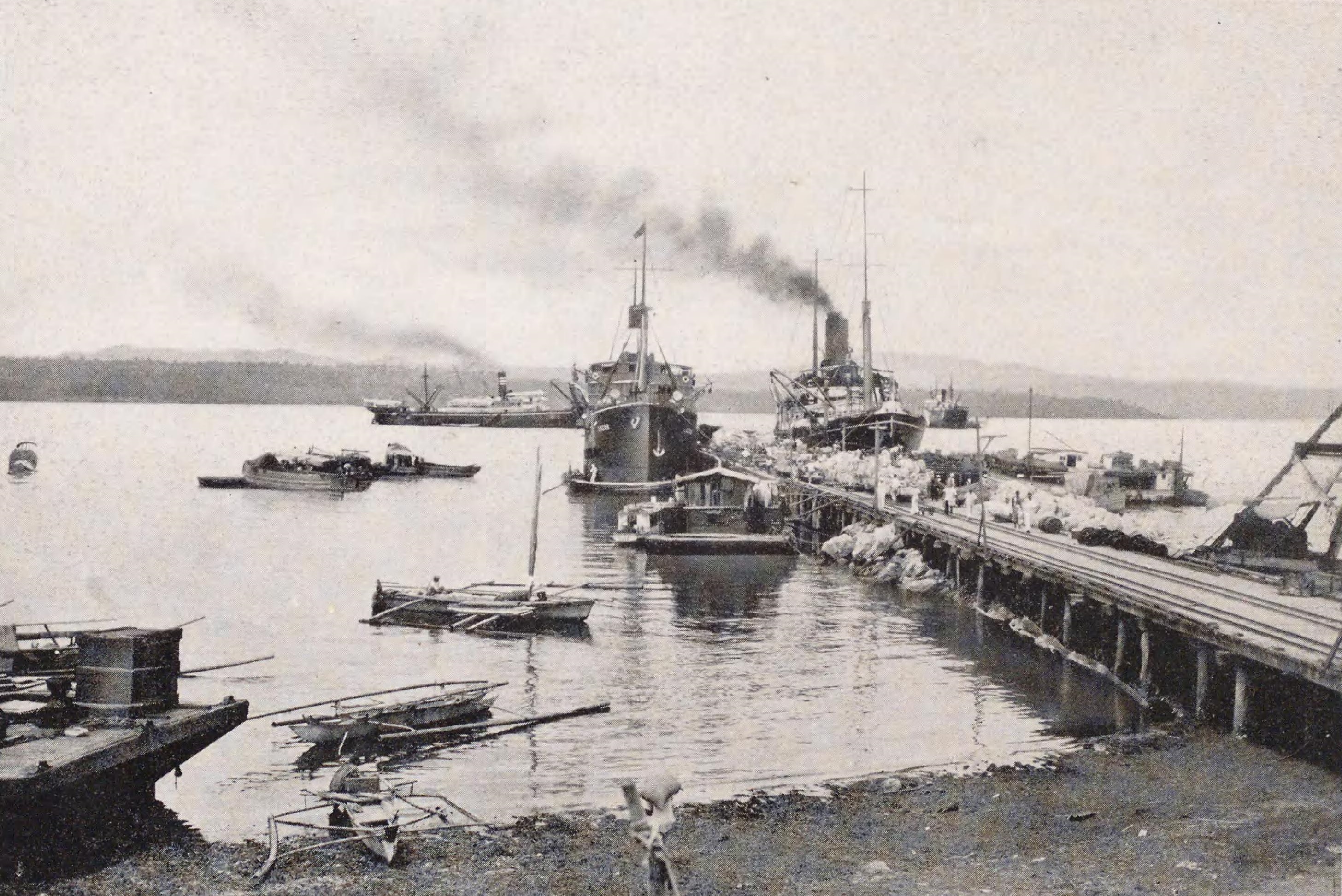

Sta. Ana Wharf in the 1920s

In the first and second part of this article, I alluded to the significant contribution of seaports to Davao’s progress (e.g., Sta. Ana Wharf in the 1920s as shown in the photo above, courtesy of Lucky Studio and the National Diet Library of Japan). Along with the ships, vessels and their sailors, stevedores made the wharfs and piers come to life and busier than usual. Some scholars and geographers would often call this introspection process as placemaking when we find meaning in public spaces as we make sense of its relevance to our lives.

Now, how do I make sense of placemaking on the footage above? Let me answer by asking the second question; why do you think Davao became the center of industry in the 1920s and 1930s? I guess one thing that we would not expect to talk about are “ropes” and rope-making. The bottom line is, Japanese companies were here, largely because of abaca (Manila hemp) production. Abaca was a major import in the USA for their cordage industry – in other words, in the production of cords or ropes, meant for ship’s rigging. Abaca plant is a species of banana known for its saltwater-resistant fiber. It turned out as an alternative source of natural fiber for the American cordage industry as it is much cheaper and do not require tarring or coating. Manila hemp is not even produced in Manila. It was called Manila since it was the port in the Philippines where the plants were shipped from. Today, Manila hemp or abaca for that matter is largely produced in Catanduanes, Bicol and some areas of Mindanao. Abaca is a million-dollar industry in the Philippines accounting for over 80 percent of worldwide production. And mind you, these natural fibers are a raw ingredient for tea bags, decorative papers, and even for our banknotes.

So how come it was a problem back then? Allow me to retrace the issue of “Davao Problem” or the so-called “Japanese Menace.” Recall the world stage in the interwar years: 1) China (Manchukuo), Korea, Taiwan was occupied by Japan’s Imperial forces; and, 2) the “Chinese Exclusion Act” was still in effect until 1943 to thwart off newcomers and further influx of Chinese refugees and emigrants in the USA and its territories in the Pacific including the Philippines.

In early 1900s American companies needed labor workers in the South. However, the influx of Japanese workers who eventually started cultivating the lands in Davao and Mindanao for agricultural purposes became an eyesore to the local businessmen and the Filipino elites in Manila. In the words of the late editor and prolific writer Nicolas V. Pacifico (1937), there was a growing anxiety that Davao was already “Nipponized” or will turn to “Davao-Kuo” someday. In 1919, the Philippine legislature passed Act 2874 which prohibited foreigners from acquiring public lands but allowed corporations provided that its Filipino capital share is over 50 percent. In the decade that followed, legal contests ensued between Japanese and Filipinos over land acquisition and settlement. But this did not stop the cordage trade in the South as abaca was a cash crop then; not until the war broke down.

According to the sources of The New World-Sun Daily, which was a leading Japanese newspaper in the US, “Japanese nationals have a monopoly of the hemp industry at Davao, which produces 75 percent of this country’s (USA) imports.” The Japanese dailies reported the following account a few months before the Pearl Harbor attack:

The (US) State Department and related agencies are also weighing the possibility of commandeering the Japanese hemp holdings in Davao, Philippines, as a defense measure. The move would be calculated to prevent a shortage of hemp, which is the raw product for ropes used in shipping and by the United States Navy (August 26, 1941).

Indeed, as I previously inferred, the nature of Japan-Philippines relations was at first economic (the 1900s to 1920s and the early 1930s); when tensions arose it became political (late 1930s), and then became militarized at the advent of WWII (1940s). I hope we are not repeating the cycle again but as they say, “history repeats itself.” (davaotoday.com)

To be continued

Andi, owing to the Japanese Romaji version of his Katakana nickname アンディ, is a loving husband to a wife, a teacher, researcher, political analyst, and a community development specialist. He finished his PhD in Japan and has travelled extensively around East and Southeast Asia.