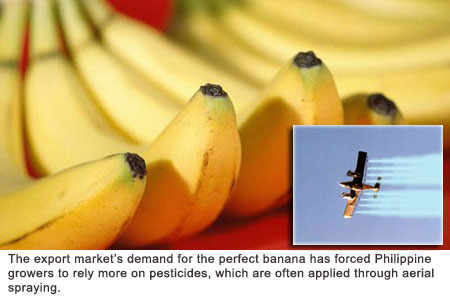

Environmentalists denounce the continued aerial spraying of pesticides in banana plantations in Davao City and Southern Mindanao. They note the havoc wrought by aerial pesticide use, among them diseases and an increasingly imbalanced ecosystem.

By Germelina A. Lacorte

davaotoday.com

DAVAO CITY — The air would smell of alquitran (tar) and the leaves of malunggay (horse radish tree) would turn into what looked like beans.

A woman from Panabo thus described what happened to her plants after the aerial spraying of a nearby banana plantation.

�I did not believe her at first,� said Josephine Quiamzon, vice-chairperson of the environmental group Panaghoy sa Kinaiyahan. �Until I saw malunggay leaves turned into what looked like monggo seeds when they fell to the ground and wilted,� she said.

During the Earth Day celebrations last week, environmentalist groups here called on government to ban the aerial spraying of pesticides, which has become a common practice among banana plantations here, according to the environment group Interface Development Interventions Inc. (IDIS).

Aerial spraying has been going on for years among the banana plantations in the Davao City barangays (villages) of Mandug, Tamayong, Manuel Guianga, Subasta and Dacudao, according to Lia Jasmin Esquillo, IDIS executive director.

�Fungicides are being applied to fight the common banana disease called sigatoka, a fungus known to infest bananas. But in doing so, they�re putting the lives of people and living things in the area in great danger,� Esquillo said of the banana companies.

Most homes in the plantation areas depend on open water sources, such as springs and wells, Esquillo said. Spray drifts, which can travel as far as three kilometers away from its source, can also contaminate the roofs of houses. Most rural homes collect rainwater to drink.

Banana companies, meanwhile, have long defended the use of aerial spraying, saying that banana diseases can have economic impact on banana-plantation workers.

�If left untreated, Black Sigatoka can quickly destroy entire banana farms,� Chiquita, one of the world�s largest banana producers, said in its website. �For workers and local communities, the impact can be especially harmful. A severe outbreak can effectively halt fieldwork, harvesting, packing, and exports for up to nine months while a farm recovers.�

Chiquita, whose banana plantations in the Philippines are all found in Mindanao, said that �currently the only effective way for commercial banana growers to control the fungus is through aerial spraying of fungicides.� Banana growers, it said, �have used aerial spraying to combat this disease since the 1960s.�

Chiquita has been sourcing its bananas from the Philippines from Lapanday Foods Corporation, which operates banana plantations in Southern Mindanao and which has been criticized by environmental groups for the alleged effects of its pesticide use, including aerial spraying, on people and the ecosystem � a charge the company has consistently denied.

Lapanday said in its website that, in all its plantations, �we employ sustainable agricultural practices and integrated pest management methodologies. We use crop protection products only when and where necessary, and always with the proper care.�

Lapanday said in its website that, in all its plantations, �we employ sustainable agricultural practices and integrated pest management methodologies. We use crop protection products only when and where necessary, and always with the proper care.�

�

The Philippines produces 12 percent of the world�s bananas, exporting more than $200 million worth of banana and banana products each year.

�

More than 60 percent of the Philippines�s fresh bananas are exported to Japan. In 2004, Japan imported from the Philippines more than 84 percent of its bananas, according to the Davao del Norte Fruit Industry Development Council (DNFIDC). Most of these bananas are produced in Mindanao, with 45 percent in Davao del Norte and 7 percent in Davao City.

Because Japan is such an important market for Philippine bananas, Japanese importers and consumers have been able to pressure Filipino banana growers to produce bananas that are in nearly perfect condition. It is said that Japanese consumers would reject bananas with even the slightest freckle, scratch or mark.

Other markets, such as Australia, have banned Philippine bananas for a variety of reasons, among them infestation by pests and freckles. Manila has since filed a complaint against Canberra before the World Trade Organization while Filipino officials and trade experts have urged a ban on Australian imports such as dairy products.

In any case, such exacting demands from banana importers and a desire to keep their market share from shrinking forced Philippine growers to rely more on pesticides, environmentalists have charged.

No One Is Spared

Dr. Romeo Quijano, a toxicologist from University of the Philippines who has done research on the alleged ill-effects of pesticide use in Lapanday�s plantations, (download the Quijano report here or view it online here) warned that no one is spared from the threat posed by these toxic chemicals, even those who think they live too far away.

Pesticide drift can contaminate open and exposed bodies of water such as river, wetlands and springs and once they�re there, they circulate in the atmosphere and can contaminate water and food sources in even in other areas, he said.

�Residues are being carried by air and water bodies. You cannot just distance yourself because there is no distance that is safe enough,� Quijano said in the Earth Day forum here. He cited toxic wastes from remote places that they found in the in the belly of fish caught in the Davao Gulf a few years back. �This could only mean that everyone is affected by what�s happening in the environment, even those who think that they are too far away from the problem,� he said.

Unpassed Ordinance

Last year, an ordinance banning aerial spraying in the city was submitted to the City Council but up to now, nothing came of it, according to Esquillo. The draft ordinance, which also provides mechanism for the gradual phase-out of aerial spraying in the city�s agribusiness firms, should have been a big leap to protect the life and health of the people. The City Council has been sleeping on it, Esquillo said.

A year ago, Mayor Rodrigo Duterte stopped the expansion of banana plantations into the city�s watershed areas. However, said Quiamzon of Panaghoy sa Kinaiyahan said, nothing has been done so far on aerial spraying, which is putting the lives of people near banana plantations in danger.

The Fertilizers and Pesticide Authority (FPA) has allowed fungicides to be applied aerially over large tracts of banana plantations in Mindanao to control sigatoka, according to a leaflet distributed by IDIS.

�It�s a pity that government, which is supposed to protect the people�s health, is neglecting (the problem), by allowing multinational companies to use aerial spraying of pesticides,� Quijano said.

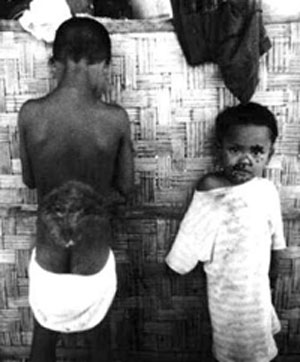

Abnormalities

He said different levels of exposure to chemicals can cause not only cancer but also mental retardation, physical abnormalities, skin diseases and various organ dysfunctions. Most medical practitioners in the Philippines are still ill-equipped to deal with chemical exposure, especially the low-level ones, the symptoms of which take years to manifest, he said.

In the 1990s, Quijano did a research in Guihing, Davao del Sur, where he attributed the high incidence of prostate and breast cancer and other illness there to the patients� prolonged exposure to pesticide in the nearby banana plantations. �Although other factors — such as malnutrition and the lack of sufficient housing — also contribute, long pesticide exposure was largely to blame for those diseases,� he said, citing similar symptoms among people living near banana and pineapple plantations in South Cotabato and different parts of Davao city.

In the 1990s, Quijano did a research in Guihing, Davao del Sur, where he attributed the high incidence of prostate and breast cancer and other illness there to the patients� prolonged exposure to pesticide in the nearby banana plantations. �Although other factors — such as malnutrition and the lack of sufficient housing — also contribute, long pesticide exposure was largely to blame for those diseases,� he said, citing similar symptoms among people living near banana and pineapple plantations in South Cotabato and different parts of Davao city.

Quijano and his journalist daughter, Ilang-ilang, later wrote about the doctor�s findings but were subsequently sued for libel by Lapanday, one of the largest banana exporters in the country that owns the Guihing plantation, among others. It denied the allegations and slapped the Quijanos with a damage suit. Lapanday is owned by the family of former agriculture secretary Luis Lorenzo Jr. Environmentalists later initiated a campaign urging the ban on the use of pesticides in banana plantations.

Imbalance in the Ecosystem

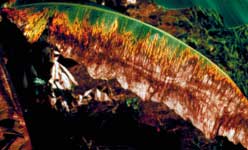

Esquillo, meanwhile, said that the use of fungicide has been causing an imbalance in the ecosystem in plantation areas. This is starting to take its toll among farmers in surrounding barangays, she said.

Precioso Yap, a farmer in the barangay of Subasta, noted a gradual decline in their coconut harvest since the start of aerial spraying in the nearby banana plantation. �At first, we noticed the leaves start to crumble and then, the young coconut fruits start to fall. Our harvests suffered,� he said.

�We used to harvest at least 3,000 nuts per hectare but now, we�re lucky if we can get 2,000 nuts per hectare,� he said. �Our recent harvests only reach as much as 1,700 to 1,900 nuts per hectare.�

Farmers noted the growing population of a kind of beetle locally known as kamaong, which infest their farm. These beetles used to feed on young coconut leaves but are now feeding on matured coconut leaves in the absence of young ones that are destroyed by the pesticide.

Esquillo said a certain fungus that used to feed on these beetles might have been wiped out by the fungicide being used by nearby banana plantations. �The sudden increase in the number of these pests must have been due to the absence of those fungi which used to check on beetle population,� she said.

In another area, hordes of rhino beetles attacking the coconut farms show the imbalance now happening in the ecosystem, she explained. Most likely, this imbalance was brought about by the prolonged use of fungicides.

Dante Delina, education and research officer of the group advocating the use of organic products, said the use of pesticides by banana plantations is threatening even the efforts among small households to ensure food self sufficiency.

�It�s still common among people in the rural areas to raise vegetables in their backyard to have something to eat,� he said. �But what happens to their backyard gardens in areas where there is aerial spraying? In Tigatto area, the toxic white dusts from aerial sprays settle on vegetables.�

�When they hear the sound of an airplane, they would run to their houses to hide,� Quiamzon said of what people in these areas would normally do during an aerial spray. �They lock their doors and windows. Others run to the chapel,� she said. �But until aerial spraying is banned in this city, no chapel is safe enough against the toxic spray.� (Germelina A. Lacorte/davaotoday.com)

Food