ISLAND GARDEN CITY OF SAMAL, Philippines – Across the Kaputian Beach Park in this city’s main island, one can see a large part of Talikud’s approximately 21.59-kilometer coastline. Talikud is one of the Samal Island’s seven islets. It is known for its white sand beaches, turquoise waters, and rich underwater life – a haven for beach lovers and diving enthusiasts. It’s a perfect recipe for a chill island life. But back in 2007, the locals were stirred with the news in the shores of Sitio Dapia, where a lifeless body was found.

In the absence of a name to call her, she was called “Princess Dapia” in recognition of the place where she was found. She weighed 300 kilograms (equivalent to six 50-kilogram sacks of rice) and measured 2.7 meters long (or about nine pieces of ruler lined up). She was believed to be nursing a young because her breasts still had milk when her body was examined.

Members of the local government unit (LGU) that took care of her remains observed for days. But her offspring was neither seen nearby nor washed ashore. The LGU was hopeful, though, that the young had survived. If it did, it would be 16 years old this year. And if it did, it would have to grow as an orphan.

Princess Dapia is a dugong (Dugong dudon) or sea cow, a gentle mammal that can grow up to 3.3 meters (almost 11 rulers) and weigh up to 430 kilograms (more than eight sacks of rice). Females of her kind get pregnant for 13 to 15 months and give birth to a calf every three to seven years. When its calf is born, it stays with her and drinks her milk for about 18 months. How many months was her calf when she died? One can never tell.

She was the first recorded sea mammal found dead nine years after the three districts of Samal were turned into a component city — now called the Island Garden City of Samal (IGaCoS).

Princess Dapia died of asphyxiation. But contrary to the written information in Kaputian Beach Park where her preserved body is displayed, it was not due to plastic indigestion. City Veterinarian Edunel Sala conducted the necropsy and found that her lungs were clogged with water as confirmed in a 2007 news report. The City Veterinarian’s Office suspected she was trapped by a fisherman’s net and was not able to surface to breath. Dugongs need to breathe air every one to six minutes though they can remain submerged for up to 11 minutes.

The main challenge in dugong conservation is the accidental bycatch that would lead to its drowning, said Gil Bigcas, Assistant Division Chief of the Conservation and Development Division (CDD) under the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR)-XI.

Most of the fishermen’s pukot (nets) are just left in shallow waters for hours and once dugongs are entangled, it would be too late to save them.

There are other challenges, such as in the Davao Oriental embayments for example, the increasing number of tourist boats and other water sports crafts like jet skis disturb the feeding areas of sea cows, said Dr. Lea Angsingco-Jimenez, regional director of the Integrated Coastal and Marine Resources Management Center.

Here in IGaCos, efforts to protect dugongs are not without challenges. For one, the city lacks the technical capacity to monitor its population, said Junemier Montera, head of the conservation section of the city’s Fisheries Division under the City Agriculture Office (CAO).

Without records or data at hand, it is difficult to gauge if its protection efforts truly have an impact.

An indicator of a coastal ecosystem’s health

In the 1990s, the government of IGaCoS already saw dugongs as an indicator of the state of its municipal waters and the state of all of its ecosystems. The mammal has been included in its official logo since 1998.

Dugongs eat up to 40 kilos of seagrass a day. As they eat and graze the sea beds, they help make them fertile and condition the population of seagrasses — the habitats of fishes.

“Although their benefits to humans are indirect, dugongs’ method of maintaining the condition of seagrasses benefits the fisheries which also benefits the people,” Bigcas said.

Dugongs play an important role in coastal marine ecosystems and the status of their population in an area indicates the general health of the ecosystem.

Herds of dugong used to ply the Philippines but their population has been reduced because of hunting and habitat destruction. Currently, they are classified as “Vulnerable to Extinction” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species.

While some populations continue to hold in Isabela, Guimaras, and Palawan, it is extremely rare to encounter dugongs. They are also found in Mindanao, though, especially in the shallow waters of the Davao Gulf.

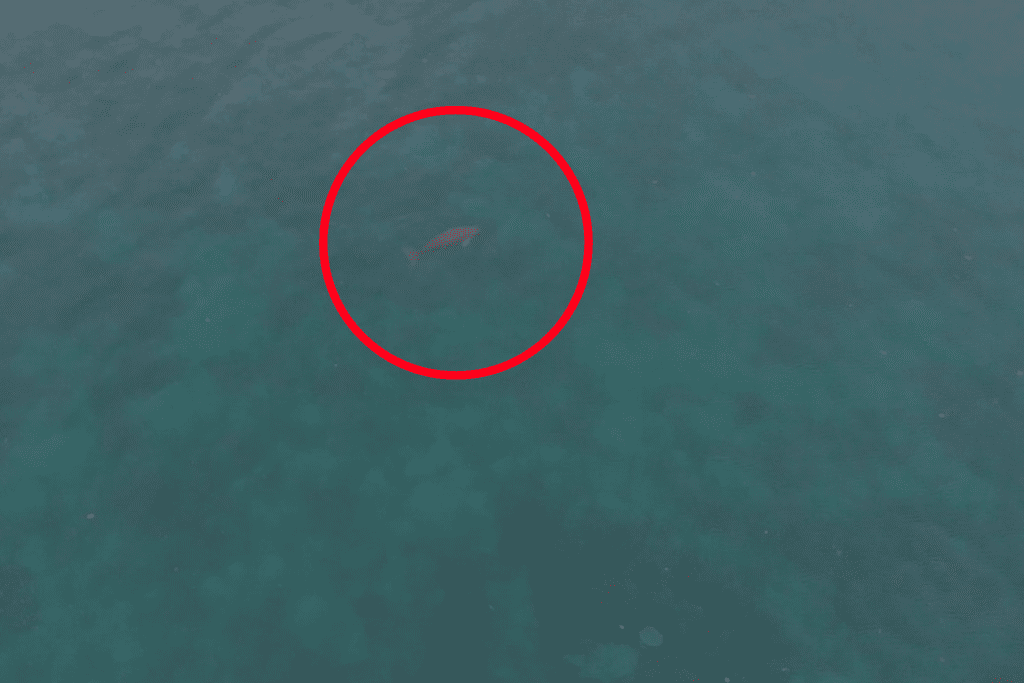

In 2019, the staff of DENR-XI’s CDD-Protected Area Management and Biodiversity Conservation Section had the privilege to see dugongs albeit from a distance. In one of their visits to Sarangani Island, their drone shots captured a big and a small dugong swimming in the waters nearby.

Dugongs are greybrown with tapered bodies that end in a deeply notched tail or fluke. They have rounded flippers that are used for balance and have high rostral deflected snouts to enable benthic foraging. Male dugongs have tusk-like incisors. Both male and female reach sexual maturity at 10 years of age and can live up to 73 years.

They are usually observed singly or as pairs. Herds with 670 dugongs seen have been the maximum recorded. The largest populations are found in Australia and then in the United Arab Emirates. They are also found in some 40 countries in tropical and sub-tropical zones where seagrass is abundant. They are more closely related to elephants than to other marine mammals like dolphins and whales.

Dugongs’ closest living aquatic relatives are the manatees who live in freshwater rivers and coastal waters of West Africa, the Caribbean, South America, and the southern United States.

Dugongs and manatees, in fact, are the only species of their type that are left in the world.

“Just like the [Philippine] eagle, dugongs are like our iconic species. We should be proud that we have them because not all countries do. It’s our cultural pride,” Bigcas said.

The Dugong sanctuary

Three years after the death of Princess Dapia, IGaCoS declared Isla Reta a dugong sanctuary through a 2010 city ordinance. The sanctuary is located at the northern portion of Talikud islet with an approximate area of 20.93 hectares. It encompasses coral reefs, mangroves, seagrass beds, and sandy substrates.

The sanctuary is part of the Sta. Cruz Marine Protected Area (MPA), one of the MPAs that the city has established and manages to protect, rehabilitate, and replenish their coastal and marine resources and habitats; to protect and conserve endangered, rare, and threatened species like the whale sharks (butanding), marine turtles, dolphins, avian species, and dugong; and to contribute to food security and ecological sustainability.

IGaCos’s protected area for dugongs is adjacent to Isla Reta, a private beach resort owned by the Reta family of Davao City. The family’s head, Mario Reta, has built a watch tower at the far end of his resort.

“That’s double purpose. It’s for the security of his resort and the conservation area. He has become our eyes and ears there”, Montera said.

If individuals fish in the sanctuary, Reta allegedly reprimands them or reports them to the coast guard, police or LGU.

“Pamusilon gani na nila ang uban dinha nga managat (They will even shoot those who fish in that area)”, said Charito Adlao, one of Sta. Cruz village’s councilors. Even the current barangay officials, she added, cannot just enter the resort unless they make an appointment.

The city’s agreement with Mario Reta has not been forged on paper. But Montera said Reta is a conservationist and has long been supportive in their dugong conservation. They also don’t have an existing Memorandum of Agreement with the current barangay LGU though they have had with the previous administration.

In the dugong sanctuary, the ordinance specifically prohibits the use of karas, seaweed culture, construction of fish cage, gathering and/or collecting any marine organism and other non-living components, and the establishment of fish corrals.

Dugong is the first marine animal that is protected by Philippine law through Republic Act 9147 or the Philippine Wildlife Act of 2001. But as early as 1991, the DENR already issued Administrative Order (DAO) 55 to conserve and protect the country’s remaining dugong population. In 2004, it declared dugongs as “Critically Endangered” through DAO 15.

Under the law, it is illegal to hunt, trade, transport, possess, or kill threatened species and products derived from them like meat. Violators could face six to 12 years imprisonment or a fine not less than Php 100,000.

Monitoring

The waters near Isla Reta are concentrated with a certain species of seagrass, the food of dugongs. This was one of the results of an IGaCoS-wide survey conducted by the Ecogroup project funded by the DENR, Montera said. This was the reason why they suggested declaring the area as a feeding ground for dugongs.

In 2009, the LGU conducted IECs (Information, Education, and Communication) in almost all puroks (sub-villages) in Sta. Cruz. Their assessment was one of the bases of the 2010 ordinance.

There was resistance at first, Montera said. Some were apprehended because they still fish in the sanctuary. But the LGU was able to make the people understand why they must not do it. The sanctuary is not really a fishing ground as there are other areas where they can fish. Eventually, people fishing in the sanctuary became less and less.

In 2012, the LGU partnered with Rare Philippines, an international non-government organization for conservation, to focus on the people’s behavioral change. Montera said they used the strategy of social marketing for the two-year “pride campaign” where they produced campaign songs, distributed collaterals, and maintained an ambassador in the form of a mascot named Gang-gang.

“We want the locals to gain pride so that protecting the dugongs will become second nature to them,” he said.

At the end of the two-year “pride campaign” in 2014, the LGU noted the people’s knowledge and acceptance increased. Resources like fishes and their habitat were also assessed.

The LGU had many partner people’s organizations before but were dissolved through the years. Now, it only has the Barangay Fisheries and Aquatic Resource Management Council, a council of fishermen, to consult from time to time. Meanwhile, its partner academe, the Davao del Norte State College (DSNC), has been focusing on the giant clams and doesn’t have a study yet on dugongs. But Montera said should the LGU requests for assessment, the DNSC is always ready to give them a hand

The awareness and pride campaign stopped. The mascot’s costume is already worn-out, no longer usable. What remains is a standee displayed at CAO at the city hall in Peñaplata District.

Montera said they do not have the data to show if the dugong population in the city has increased since the sanctuary was established. They only rely on testimonies, on reported sightings they receive until today. “We don’t have the technical capacity to monitor its population”, he said.

After Princess Dapia, a number of sightings including those seen by divers were relayed to CAO. There were sightings in Talikud and in Tambo, Babak. In 2003, a sea cow was reportedly found dead in Talikud but it was not documented. Another one was reported before the COVID-19 pandemic. But CAO was uncertain of the cause of death though they suspected it was hit by a boat propeller or it died from another place and was only washed ashore. The dugong was already in a state of decomposition and the office decided to bury it instead of conducting the necropsy.

Lloyd Intong, a fisherman, who lives on a beachfront in Kaputian said he saw dugongs in his area and in Isla Reta. A group of Badjao fishermen from Davao City’s Piapi Boulevard also claimed sightings near Isla Reta.

“Daghan man gud kaayog lumot (dinha sa Isla Reta dapit), kanang makaon sa dugong. Gusto nila katong lumot nga tag-as, murag cogon grass gani. Tag-as man na dinha (Seagrasses are abundant in Isla Reta, the type that dugongs eat. They love the tall seagrasses like the cogon grass.)” Adlao said.

But the LGU doesn’t have a particular research on dugongs or the seagrass that they feed on.

In 2007, the DENR XI conducted a survey in IGaCoS on the seagrass, corals, and mangroves but only as to the distribution, said Bigcas, With regards to the details on the community of seagrass, there is no survey or study yet. He said IGaCoS is a big area and would require a lot of time to conduct a specific study.

The dugongs, he said, only eat the Halophila type of seagrass and it can be found in the stretch of Isla Reta. Out of the 16 species of seagrasses in the Philippines, Bigcas said, 11 or 12 can be found in Region XI but are distributed in different areas. The Pujada Bay in Mati has nine to 10 species but not all can be found in Balut Island in the municipality of Sarangani. Balut Island has two species that cannot be found in Pujada Bay, but it has a common species in Baganga, Davao Oriental. A unique species of seagrass (Thalassodendron ciliatum) can only be found in Balut Island in the entire Davao Region.

Montera expressed their difficulty to monitor the dugongs and said maybe they are the same that are seen in other areas of the Davao Gulf because of their migratory nature. They cannot say if the dugongs are “residents” of IGaCoS.

Although dugongs are migratory in nature, Bigcas said, their navigation is anchored at the sea bottom and would only navigate in adjacent areas. If the sea bottom is deep and dark, they get disoriented and would refrain from crossing. So it is possible that the population of dugongs in IGaCoS are ‘residents’.

Dugongs also have a different area for playing and another area for mating. They will not just stay in one place but considerably stay in shallow waters.

Challenges

For the past five years, Montera said one of the challenges is the lack of personnel. He is the only one assigned to the protection of the city’s 18 MPAs. While the city hired JOs (job orders) to help him, it is only for selected areas.

With his workload, he said it’s difficult to have a clear output. But with their current reorganization, he hopes that additional staff could lessen the burden. He reiterated the lack of technical capacity in monitoring dugongs, especially their population.

Funds, he said, is not really an issue because the LGU allots an annual budget for the MPA program, though the amount varies. The Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources also gives assistance through the bottom-up budgeting, which allows them to construct guardhouses for their bantay dagat (sea patrol) and distribute food supplies. To cut expenses, they partnered with the barangay LGUs to assign some members of their civilian volunteer organization as bantay dagat. `

Two bantay dagat members are assigned at the guardhouse in Dapia, monitoring 24 hours a day. Their assignment is the entire Brgy. Sta. Cruz which has two MPAs. The two are focused on the fish sanctuary because Mario Reta, Montera said, already guards the dugong sanctuary.

Documentation is also a challenge. His section does not have the records and pictures at hand, because they cannot retrieve them anymore. Apparently, they don’t have an established system in this regard.

Hope

Montera said they are in the process of revising the MPA ordinance since the city has a number of MPAs including lone ordinances either declared by the city or the barangays. They hope to make a comprehensive one to address the gray areas on certain policies and adjust the boundaries.

As to the dugongs, Montera said, for now, they can only do their best to protect the areas against destruction. He hopes that no major developments will affect them in the future such as siltation from the uplands that will affect the reefs.

He said that once the Davao to IGaCoS Bridge is constructed, development will eventually focus in Talicud that could result in the increase of ferry boats. The port of Sta. Cruz would expand and drillings would affect the seagrasses. “I hope the conservation will be institutionalized, not just for dugongs”, he said.

For Bigcas, there should be a continuing effort to educate the people because environmental concern is not only the concern of the government but of the general public. (Marilou Aguirre-Tuburan/davaotoday.com)

This story has been produced through support from USAID SIBOL, in partnership with AYEJ, under the Green Beat Plus biodiversity journalism training program. The content and publication of the report are the sole responsibility of the author and the publisher.

dugong, environment, Mindanao, samal, sea cow