In the book Alternative Media, Atton grounded the concept of alternative media on a Marxist analysis of radical and anti-capitalist relations of productions coupled to “projects of ideological disturbance and rupture”. Fuchs in his journal, Alternative Media as Critical Media, likewise argued that alternative media are not mere alternative media practices, but, critical media that challenge the “dominative” system, structure and society.

In this article, allow me to revisit the major climacteric contributions of the alternative media to the rise of social movements that rally behind the fundamentals of press freedom. Here, I am interested in questions like: What makes alternative media “alternative”? And what are its epistemological presuppositions in relation to the history and politics of Philippine media?

Guided by scant literature on alternative and critical media, a couple of common keywords constitute the formation of alternative media in the areas of media audience, news themes and issues, and, purpose and functions.

First, the marginalized and vulnerable sectors of society including the workers, indigenous peoples, women, and children among others are the foremost audience of alternative media. By audience, we mean that the news reportage is inspired by the grounded narratives of these sectors and they too serve as the central recipients of the news. As active participants in the disposition of news, the audience are assured of occupying a democratic space in the reproduction of public sphere. Second, the news themes are geared towards economic, political, cultural, and development issues that perturb the struggles of the marginalized e.g., militarization of Lumad communities in Mindanao, policies on contractualization foisted by multinational corporations, decade-long cases of impunity that traversed various presidential regimes including the Marcos-sponsored martial law, mass killings of farmers and workers in Mendiola and Hacienda Luisita under Cory Aquino, Ampatuan-Maguindanao massacre and cases of human rights violations, like enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings under Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, and the horrendous situation of the victims of Super typhoon Yolanda (typhoon Haiyan) and displacement of Lumad and other indigenous groups in Mindanao under Benigno Aquino III. And lastly, the salient point of alternative media is to expose socio-political issues that are commonly blocked or neglected by the corporate dominant media. The means of achieving such purpose largely depends on the sustained investigative, participatory and grassroots-based organizing approaches to alternative media reporting that aim to serve as a catalyst for radical social change.

Now, let us re-imagine the major historical breakthroughs in Philippine alternative media.

Maslog outlined the historical development of journalism and mass media in the Philippines from the colonial and censored journalism during the Spanish colonization (1521 to 1900), elite-inspired distribution of ownership of the media during the American colonization (1900 to 1946), repositioning of Manila-centered mass media during the Post-War Period (1946 to 1972), and to the imposition of Martial Law by Marcos (1972 to 1986).

According to Kabatay and Teodoro, the suppression of the Filipino peoples’ right to information and freedom of expression during Martial Law triggered the proliferation of alternative media outfits including publications of religious and cause-oriented organizations like Signs of Times, University and College newspapers like Philippine Collegian, “xerox media” (photocopied articles from foreign publications that lambasted the Marcos regime), and clandestine press of the Left-underground movement like Liberation and Taliba ng Bayan (The People’s Herald). Marcos issued a number of Presidential Decrees (PD) that directly negated the very essence of a free press, including PD 1737 which “empowered the President to issue orders directing the closure of subversive publications or other media of mass communications, among others” and PD 1834 which increased the “penalty of life imprisonment to death on any person who, having control and management of printing, broadcast or TV facilities, or any form of mass communication shall use or allow the use of such facilities for the purpose of mounting sustained propaganda assaults against the Government.”

From 1976 to 1986 alone, at least 25 journalists from the underground and above-the-ground press movement were reportedly killed by State forces. Resistance in form of underground, revolutionary and mosquito press publications against Marcos gradually took place at the time and eventually formed part of the peoples’ coalition that overthrew the rule of the dictator.

Fast forward to the present.

The emergence of media watchdogs and alliances of progressive and alternative media outfits, like Altermidya, affirmed the incessant struggle for a genuine free press. As the false promises of democracy in 1986 continuously hound us, the more there is a need to be circumspect in the policies, practices and attitude of the State towards one of its conventionally dubbed critics – the alternative media.

Decades ago after Martial Law, the stumbling blocks that infringe on the freedom of the press remain selfsame. The assaults on the media persist under impunity with over 170 journalists and media workers killed since 1986; the laws and regulations still serve as instruments to threaten, and worst, disregard the fundamentals of free speech and expression as in the case of filing libel suits against community journalists, and now, with its online and stretched version in the Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012; contractualization is still widely practiced both in the dominant and community media outfits; red-baiting and Communist-tagging are still part of the State military tactics against critical and investigative media outfits; and yes, the Manila-centric and perverse media ownership as initially highlighted by Maslog remain evident.

Of course, the alternative media do not wish to unriddle these puzzling situations. They are indeed more vulnerable to attacks by the apparatuses of the State. But in spite of unabated threats against, harassment and killings of journalists and media workers especially those operating in the community and alternative media, alternative media platforms of book publishing, radio, online, print, and multimedia thrive to fulfill its function of serving not only as a watchdog of democracy, more importantly, as instigator of public discourse immersed in the sorry state of the marginalized audience it vows to fortify.

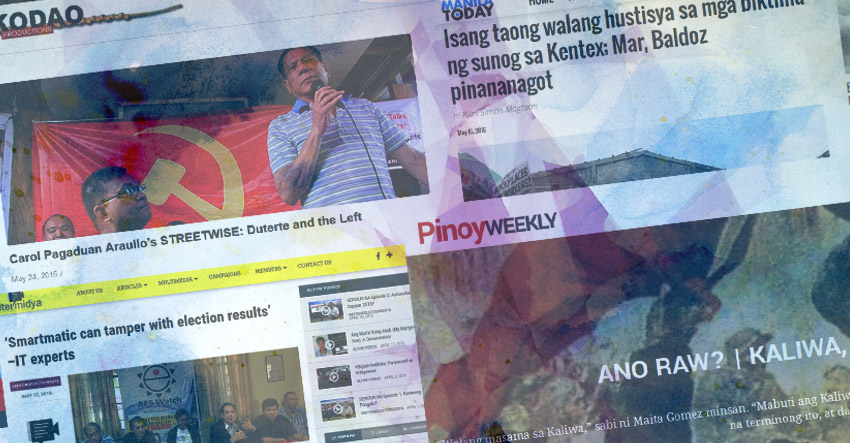

The traditional print, Internet and multimedia platforms pave way for keeping up the operations of some alternative media outfits in the country such as Bulatlat.com, Davao Today, Northern Dispatch, Pinoy Weekly, Kilab Multimedia, Pinoy Media Center, and Kodao Productions. The means of investigating, documenting and reporting on the plight of the marginalized are utilized in a critical multi-modal approach to grassroots alternative journalism which seeks to stimulate sense appeals to the media audience.

If the marginalized sectors serve as the principal audience of the alternative media, it is logical to capitalize on such media considering its inherent function to mobilize the grassroots communities towards defending the promises of a free press. Our concerted agenda for a genuinely working free press – putting an end to media killings and impunity, scrapping contractual labor, passing a pro-people Freedom of Information Law, decriminalization of libel in print and online forms – are ever put in compromise by the dominative capitalist system that the alternative media aims to challenge and radicalize.